5 Minutes

What Is Astigmatism and Why Does It Happen?

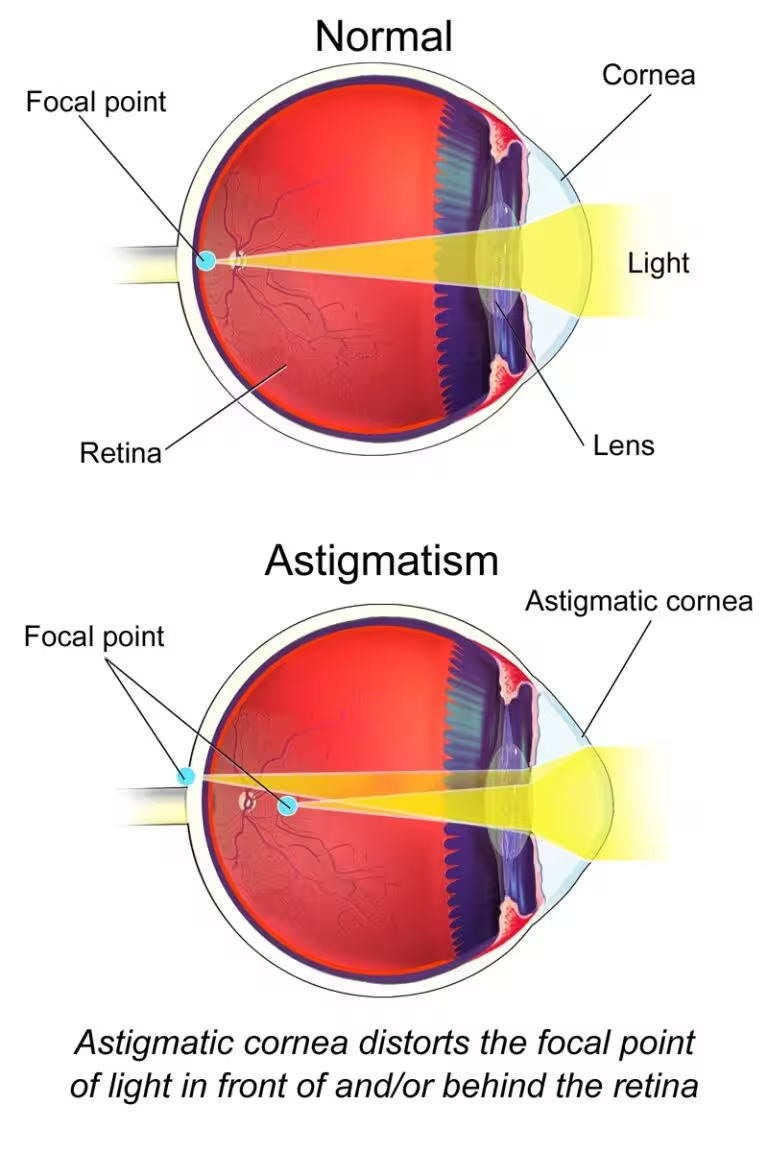

Astigmatism is a prevalent refractive eye condition, affecting an estimated 40% of people worldwide. Unlike a perfectly round eye, individuals with astigmatism have eyes where the cornea—the clear front surface of the eye—is shaped more like an oval or a football than a sphere. This irregularity disrupts the way light focuses on the retina, causing blurry, distorted, or unfocused vision.

In a healthy eye, the cornea and lens act in concert to refract (bend) incoming light precisely onto the retina at the back of the eye, similar to how a camera lens projects an image onto film. Deviations in any of these structures' size or curvature can lead to a spectrum of refractive errors—most notably astigmatism.

Astigmatism is categorized into two principal types:

- Regular astigmatism: The more common form, arising primarily from the cornea’s oval shape, often due to hereditary factors. The eye’s surface remains smooth and predictable, just misshapen.

- Irregular astigmatism: Less frequent and typically linked to corneal scarring, growths, or diseases like keratoconus—where the cornea thins and bulges outward into a cone shape, creating unpredictable irregularities.

This irregular curvature prevents light from converging at a single focal point, resulting in symptoms such as double vision, ghosting, reduced contrast sensitivity, glare, and heightened sensitivity to bright lights.

The History and Scientific Context of Astigmatism

The phenomenon of astigmatism has been explored for centuries. In 1727, Isaac Newton described how light waves are altered by irregular surfaces. Later, in 1800, English scientist Thomas Young—who himself had astigmatism—publicly detailed how the condition impacted his sight. Star astronomer Sir George Airy contributed a major breakthrough in 1825, discovering that tilting his lenses improved his vision, which led him to pioneer cylindrical lenses for astigmatism correction. The term “astigmatism” itself, introduced by William Whewell in 1846, comes from Greek roots meaning “without a point” or “without focus,” referencing the condition’s hallmark: lack of a single, clear point of vision.

Diagnosing and Measuring Astigmatism

How Optometrists Assess Astigmatism

Astigmatism is routinely detected during comprehensive eye exams, particularly in the refraction process. Here, eye care professionals use an array of lenses to pinpoint the unique prescription needed for spectacles or contact lenses. For more complex cases, such as irregular astigmatism, advanced imaging technologies like corneal topography come into play. This technique produces a detailed three-dimensional map of the cornea, highlighting subtle bumps, warps, or surface inconsistencies that standard exams may miss.

Living With Astigmatism: Symptoms and Progression

Astigmatism can affect individuals at any stage of life, though its incidence often increases with age. While mild astigmatism may go unnoticed, higher degrees can result in significant visual disturbances—blurring, difficultly focusing, eye strain, or headaches. Moreover, the severity and pattern of astigmatism can shift over time, necessitating regular vision assessments to ensure optimal correction.

Vision Correction Options: From Glasses to Advanced Technology

Today, a wide spectrum of options are available for managing astigmatism:

- Cylindrical prescription lenses: The standard solution for regular astigmatism. These are calibrated specifically to counteract the eye’s uneven curvature and are widely available as eyeglasses or soft and rigid contact lenses.

- Laser Vision Correction: Refractive surgeries like LASIK use precise lasers to reshape the cornea, directly addressing the irregularities that cause astigmatism.

- Orthokeratology (Ortho-K): A non-surgical approach utilizing rigid contact lenses worn overnight, temporarily reshaping the cornea to provide clear, lens-free vision during waking hours.

- Specialty Contact Lenses for Irregular Astigmatism: Hard or rigid gas permeable lenses can mask surface irregularities much better than glasses or soft lenses, especially useful in conditions like keratoconus.

- Corneal Surgery: In severe or non-responsive cases, surgical procedures such as corneal transplants may be required to restore corneal shape and integrity.

Early intervention and tailored treatment strategies are essential for preserving long-term vision quality. It's vital to address not only the astigmatism itself but, where necessary, any underlying conditions responsible for corneal changes.

Astigmatism and Children: What Parents Should Know

Refractive errors, including astigmatism, can emerge in early childhood and sometimes evade detection unless regularly screened for. Significant astigmatism may interfere with children's learning, athletic performance, and social development. If left uncorrected, moderate-to-high astigmatism may even trigger other issues such as amblyopia (commonly known as "lazy eye") or strabismus (eye misalignment). While astigmatism itself is not inherently dangerous, timely diagnosis and correction are pivotal for healthy visual development. Regular pediatric eye exams equip parents with the best chance to catch and correct vision issues before they impact learning and lifestyle.

Future Directions and Vision Science Innovations

Ongoing research in ophthalmology and vision science is yielding new insights into the genetic and environmental factors influencing astigmatism. Innovations such as wavefront-guided laser treatments, adaptive optics, and advanced lens manufacturing promise even more personalized and effective care in the future. Public health campaigns emphasize the value of routine eye examinations for all ages, aiming to reduce long-term visual impairment from undiagnosed refractive errors.

Leading eye health organizations like the World Health Organization and the American Academy of Ophthalmology advocate for global access to eye care and advances in vision correction technology, recognizing that optimal sight improves quality of life across populations.

Conclusion

Astigmatism is a remarkably common vision condition, shaped by the intricate interplay of eye anatomy, genetics, and environmental influences. Thanks to advances in optometry and ophthalmology, most forms of astigmatism are now highly manageable, whether through glasses, contact lenses, surgical interventions, or innovative orthokeratology techniques. Early detection remains key—particularly in children—to safeguard against developmental setbacks. As technology continues to evolve, the future of astigmatism management will likely become even more precise and accessible, brightening the outlook for millions worldwide seeking clear, sharp vision.

Source: theconversation

Comments