3 Minutes

Unveiling an Ancient Enigma: Identifying the Bronze Jar’s Secret

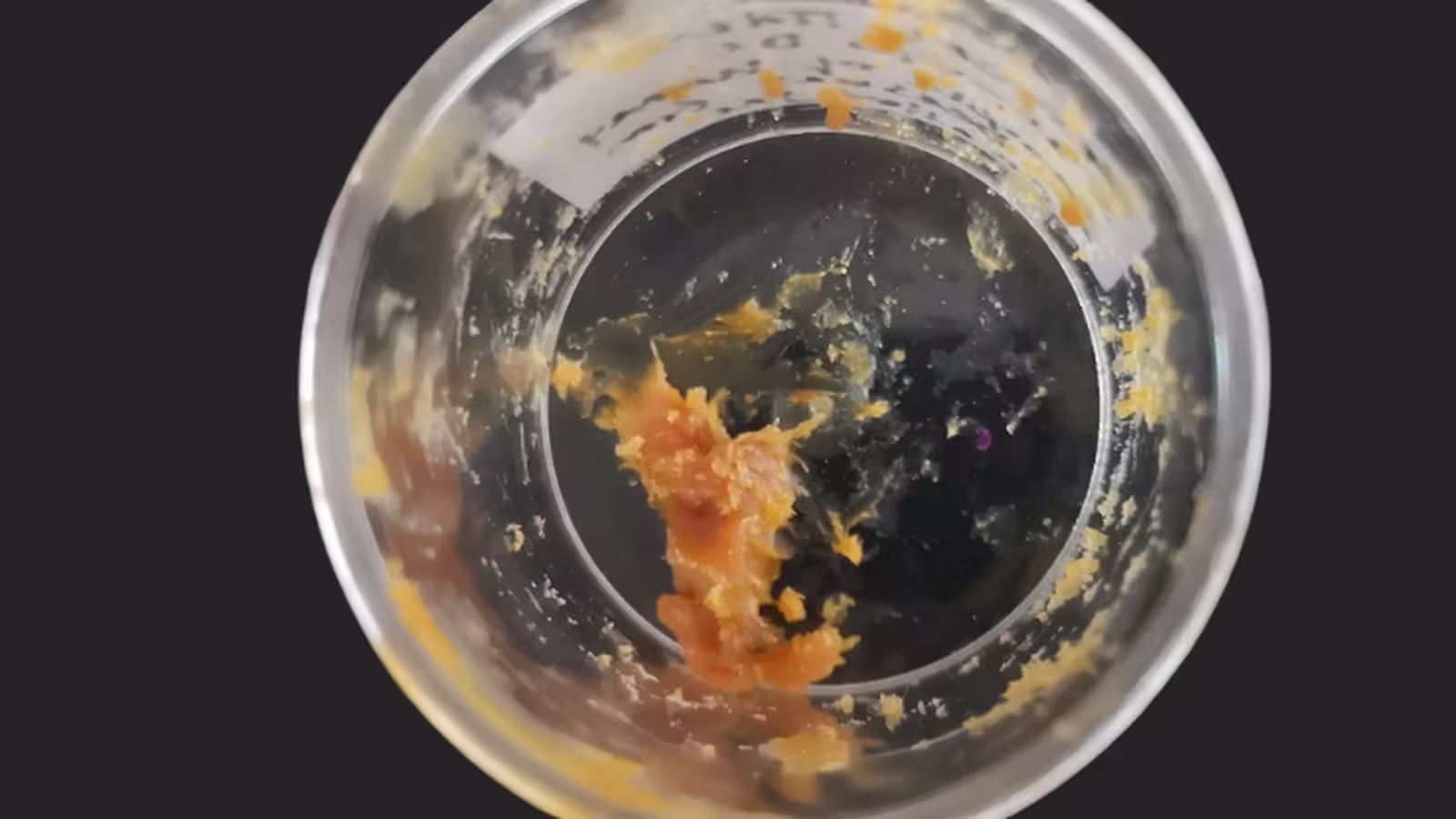

Decades after its initial excavation, an enigmatic orange residue discovered in a bronze jar at a 2,500-year-old shrine near Pompeii, Italy, has been conclusively identified as honey. This significant breakthrough provides rare insight into ancient Greek rituals and the chemistry of organic preservation, deepening our understanding of early Mediterranean societies and their sacred offerings.

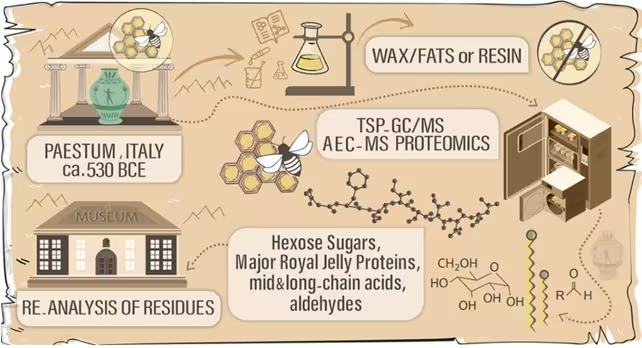

Scientific Context and Analytical Techniques

First unearthed in 1954 within a Greek sanctuary in Paestum, southern Italy, the mysterious substance inside the corroded vessel resisted identification for decades. Prior chemical analyses had failed to determine its organic components, largely because time and environmental conditions had altered its makeup.

A research team led by archaeologist Luciana da Costa Carvalho of the University of Oxford finally solved the puzzle using cutting-edge techniques—specifically, gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. These advanced instruments allowed the scientists to isolate and identify chemical markers within the residue, including a signature pattern nearly identical to modern honey and beeswax.

Degradation and Preservation in Archaeological Materials

The findings showed the substance was notably more acidic than contemporary honey—a result consistent with long-term storage and chemical transformation. Over centuries, sugars in the honey gradually degraded into compounds known as furans. Previous tests had identified beeswax, but the complex profile of the residue pointed clearly to a mixture of honey and its byproducts, rather than wax alone.

Importantly, the latest analysis detected the presence of hexose, a simple sugar, along with degraded saccharides—clear evidence of the original honey components. These carbohydrate traces had persisted, preserved by the copper corrosion of the ancient vessel.

Archaeological Significance and Cultural Insights

The shrine, dedicated to an unknown deity, featured bronze jars placed around an empty iron bed, alongside six hydriai (water jars) and two amphorae (storage vessels). According to da Costa Carvalho and her colleagues, the empty bed and impenetrable nature of the shrine signified divine presence. Offering honey as a “gift to the gods” reflects its dual symbolism in ancient Greek culture—both as a sweet delicacy and as an emblem of immortality, famously said to be part of the diet of Zeus in myth.

In classical antiquity, honey was also prized for its wide-ranging uses, from natural sweetener and medicinal ingredient to a vital element in religious rites and cosmetics. This discovery not only reinforces our knowledge of these practices but also demonstrates how ancient organic residues are intricate chemical ecosystems.

As da Costa Carvalho notes, “Ancient residues aren't just traces of what people ate or offered to the gods – they are complex chemical ecosystems. Studying them reveals how those substances changed over time, opening the door to future work on ancient microbial activity and its possible applications.”

Conclusion

The identification of 2,500-year-old honey at the Paestum shrine marks a milestone in archaeological science, illuminating the sophisticated nature of religious offerings and organic preservation in ancient Greece. With the combined power of modern analytical chemistry and thorough archaeological context, such discoveries enhance our appreciation of the relationship between ancient culture, ritual, and science—and pave the way for further exploration into the microscopic worlds preserved in history’s vessels.

Source: pubs.acs

Comments