5 Minutes

Behind the door: a small moment, a big take

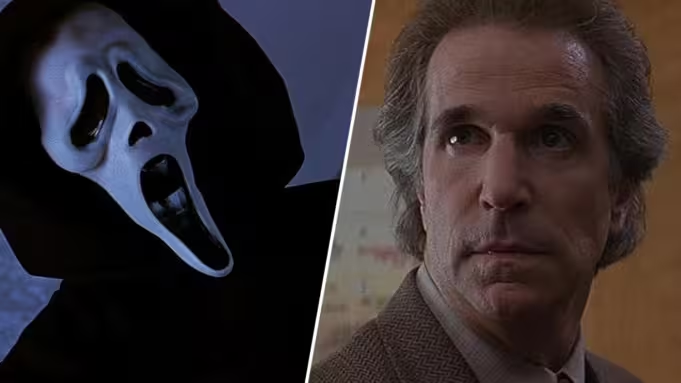

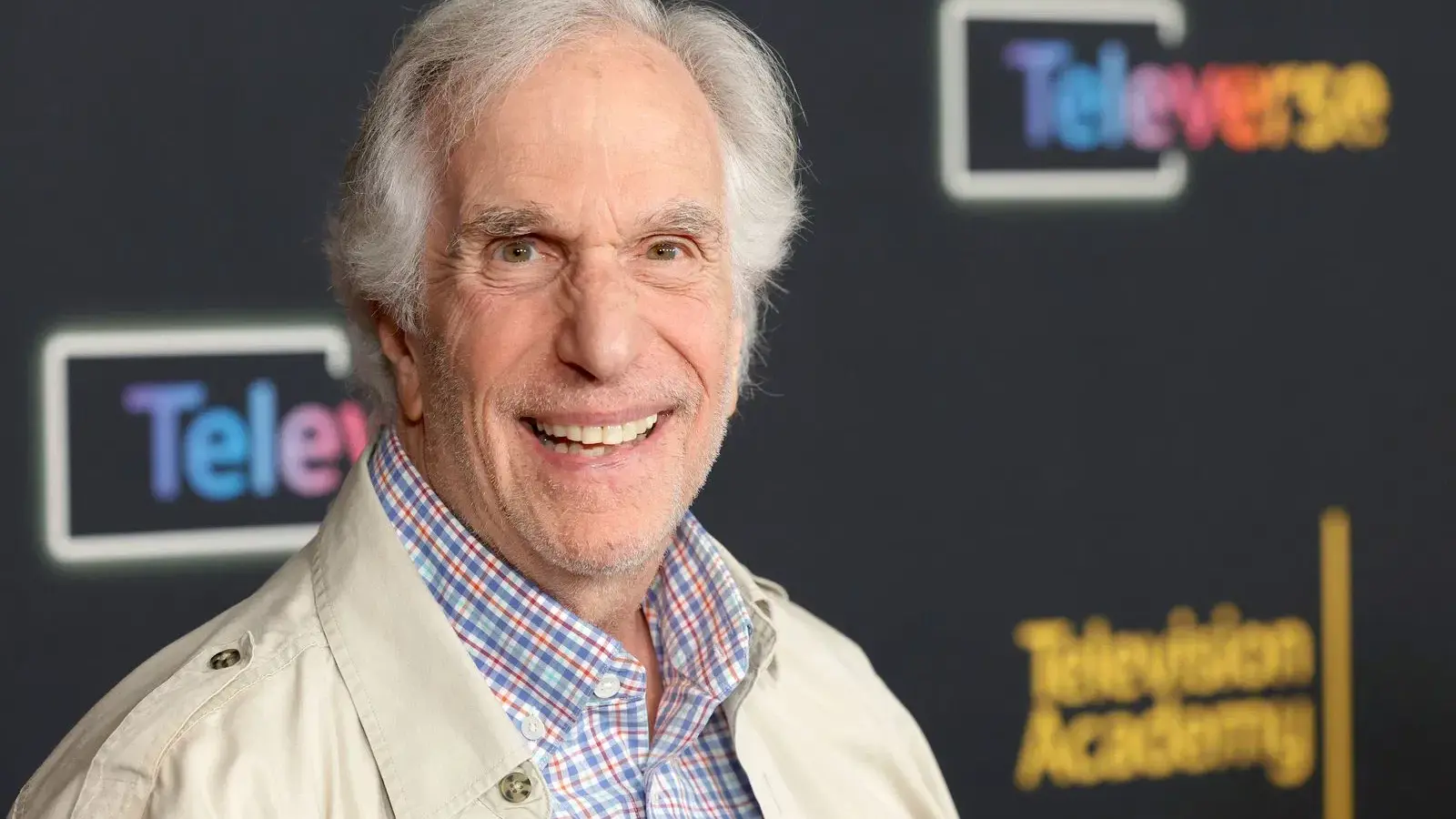

One of the most memorable, if briefly seen, confrontations in Wes Craven and Kevin Williamson's 1996 Scream didn't rely on special effects or elaborate camera tricks. It hinged on a tiny, human interaction: Henry Winkler — forever associated with The Fonz — goading a fanboying stuntman into delivering the exact burst of menace the scene needed.

Stunt performer Lee Waddell, who wore the Ghostface costume for several kills in the original Scream, recently recounted the exchange during a GalaxyCon Q&A. Waddell admitted he was starstruck on set; he grew up with Happy Days and says he 'geeked out' around Winkler. That enthusiasm, he confessed, curbed the intensity he brought to a key stabbing scene. Instead of an instantaneous reaction from Winkler's Principal Himbry, the takes were soft and Waddell was running out of options.

Winkler's solution was improvisational and old-school. He pulled Waddell aside, stepped fully into the hateful principal persona, and began needling him physically and verbally. According to Waddell, Winkler lightly hit his shoulder and swaggered into character, telling him 'I'm gonna suspend you' and getting in his face. The jab flipped a switch. Waddell says he snapped into Ghostface — furious, focused — and finally gave Winkler the violent energy the scene required. That charged exchange made it into the final cut.

It's a small anecdote, but it illuminates two larger realities about cinema: the invisible choreography between actors and stunt performers, and the value of veteran instincts on set. Winkler's riff was part coaching, part performance, part provocation — and it worked.

Beyond the anecdote itself, the story is also a reminder that Scream's success came from a blend of affection for horror conventions and skilled, on-the-ground filmmaking. Wes Craven's direction always left room for actor impulses, and Kevin Williamson's script leaned on real emotions — fear, anger, humiliation — that actors could mine. In that sense, Winkler's intervention is very much in the Craven tradition: subtle, human, and occasionally mischievous.

Comparisons to other on-set moments are natural. Directors and seasoned actors have long used provocation to sharpen performances — from method techniques of the classic era to contemporary actors who still push each other to find authentic reactions. But there's a fine ethical line: what works in one setting can feel abusive if misapplied. Winkler's approach, as Waddell tells it, was playful and consensual enough to produce a great take without crossing that line.

For fans of Scream and horror history, there are nice trivia points here. Waddell returned to don the Ghostface costume again in Scream 2 (1997), a fact that underscores how often stunt performers become repeat fixtures in horror franchises. Winkler — better known for comedic warmth — showed the range that made his cameo as the despised principal memorable, and the fan community still cites this moment as an example of casting against type paying dividends.

Film craft enthusiasts will also note a broader industry trend: while CGI and VFX have expanded what's possible, the raw interaction between performers remains irreplaceable. Stunt performers and practical actors still supply immediacy that effects can't replicate.

Film historian Elena Marquez offered a quick take on the exchange: 'This moment shows how performance is collaborative. A single improvisation can elevate a scene from adequate to iconic, especially in a genre that thrives on jolts and surprise.' She adds, 'It's also a reminder that horror often depends less on spectacle than on tiny, human-powered beats.'

Waddell's anecdote about Winkler is a small backstage jewel — a peek at how seasoned actors, stunt performers, and directors create the pulse of a scene. It may be a brief episode in Scream's long afterlife, but it captures the movie's mix of reverence for horror tradition and kinetic, down-to-earth filmmaking.

Source: deadline

Leave a Comment