6 Minutes

Michèle Burke: a life in faces and film

Michèle Burke, one of cinema's most respected makeup artists and the first woman to win an Academy Award in makeup, died on September 26 in Los Angeles at the age of 75. Her career spanned more than five decades and more than 50 feature-film and television credits, from prehistoric epics to gothic horror and high-budget blockbusters. Burke's work helped define the look of some of the most memorable characters in modern film — and changed how the industry viewed makeup as a storytelling tool.

Early years and the rise from Dublin to Hollywood

Born on December 29, 1949, in Dublin, Burke emigrated to Canada in the 1970s amid economic uncertainty at home. What began as a job in fashion and as a Revlon demonstrator in department stores evolved into a passion for cinematic transformation. After unpaid work experience with Montreal makeup artist Mickey Hamilton, Burke found her feet in the city's busy film scene — a scene buoyed at the time by tax incentives that brought horror and genre shoots to Canada.

Her first solo film credit was the 1980 slasher Terror Train, starring Jamie Lee Curtis. But it was Jean-Jacques Annaud's Quest for Fire (1981) that brought international attention. Sharing the 1983 Oscar for Best Makeup with Sarah Monzani for Quest for Fire, Burke became the first woman to win in that category — an important milestone in a craft historically dominated by men.

Signature films and collaborations

Burke's credits read like a tour of late 20th-century cinema: Interview with the Vampire (1984), Cyrano de Bergerac (1990), Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992), The Cell (2000), and Austin Powers: The Man Who Shagged Me (1999), among others. She shared a second Oscar in 1993 with Greg Cannom and Matthew W. Mungle for Francis Ford Coppola's Bram Stoker's Dracula, a film whose elaborate prosthetics and period styling helped reassert practical makeup effects as an art form in the age of emerging digital tools.

A through-line in Burke's career was long-term collaboration. Her work with Tom Cruise began in Neil Jordan's Interview with the Vampire, where she created Lestat's distinct, pallid, and aristocratic vampire look. That initial collaboration led to decades of trust: she later worked with Cruise on Jerry Maguire, Vanilla Sky, Minority Report, Mission: Impossible III and Ghost Protocol, Oblivion and more. Burke also applied her craft to actors as diverse as Sharon Stone, Penélope Cruz and Brad Pitt, always tailoring technique to actor and story.

Craft and philosophy

Burke described her approach succinctly: she looks at the "totality" of a performer — hair, skin tone and the narrative the director wants to tell. Her work balanced subtle character shading with show-stopping prosthetics. In an era when CGI was becoming more prevalent, Burke remained an advocate for the tactile truth that practical makeup brings to performances and camera work.

Behind-the-scenes stories from shoots underline that philosophy. On Quest for Fire she helped create convincing prehistoric aesthetics with limited materials; on Dracula the team mixed traditional prosthetics with theatrical lighting and costume to produce the film's now-iconic, baroque visage. Fans of genre cinema have long praised those looks, and Bram Stoker's Dracula continues to be a reference point in discussions about gothic makeup design.

Industry recognition and legacy

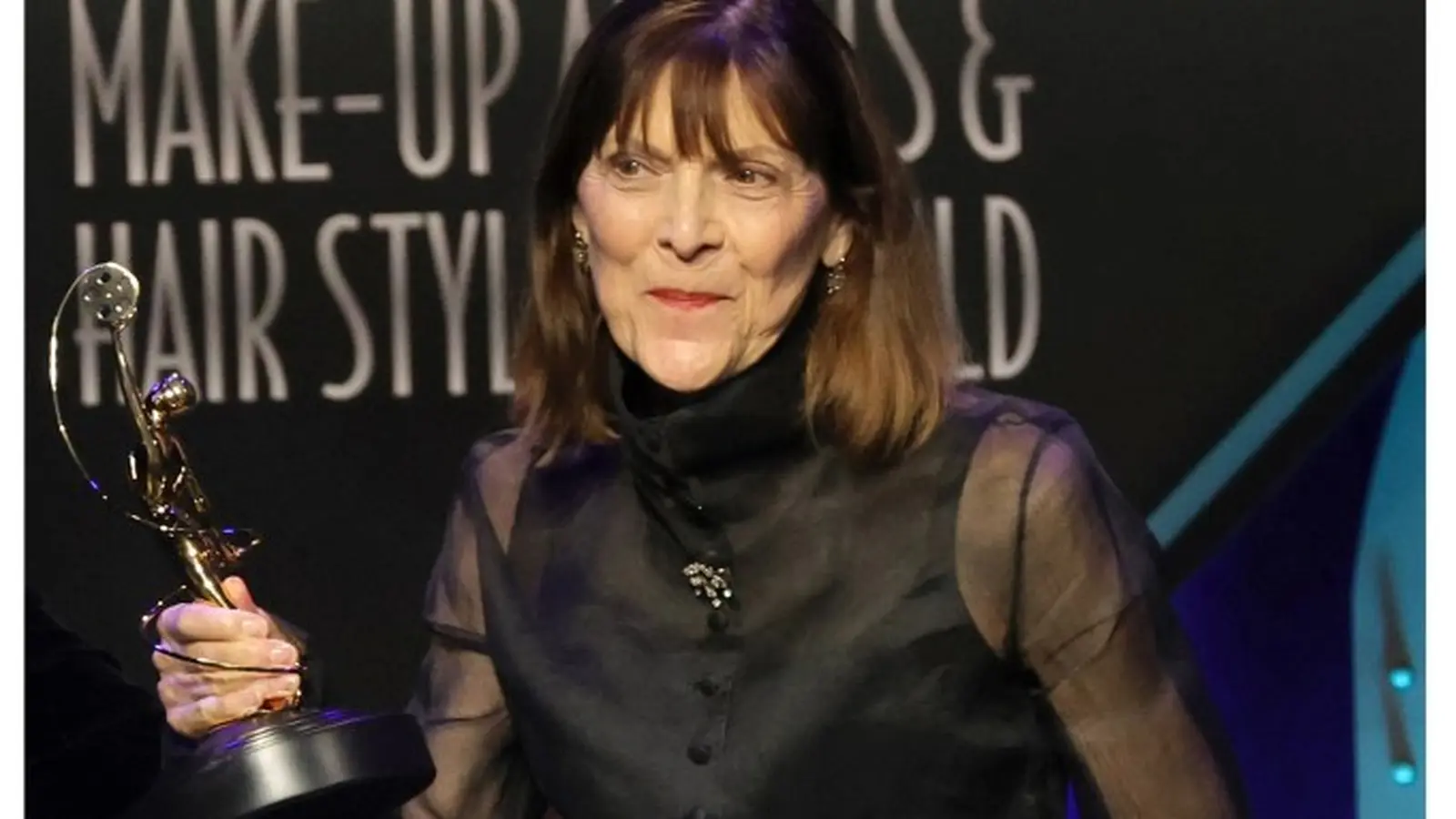

Beyond her two Oscars and multiple nominations (including for The Clan of the Cave Bear, Cyrano de Bergerac, Austin Powers and The Cell), Burke received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Make-Up Artists & Hair Stylists Guild in 2022. Her influence can be traced through contemporary makeup artists who cite her precise color work, careful blending and character-first mindset as guiding principles.

"Burke transformed the idea of screen makeup from mere glamour into character architecture," says cinema historian Lena Morales. "She treated faces like landscapes — every wrinkle, tone and hairline a narrative choice. Her legacy is visible in every film that prioritizes character through craft."

Context and comparison

Burke's position in film history sits alongside other practical-effects legends such as Greg Cannom and Rick Baker. While Baker is often associated with creature work and Cannom with aging and transformation, Burke excelled at marrying period authenticity with theatrical exaggeration when the story demanded it — a balance especially evident in period dramas like Cyrano de Bergerac and genre pieces like Dracula.

Her career also maps onto broader industry shifts: the 1980s and 1990s were a golden era for practical makeup and prosthetics, and Burke's work helped keep that craft prominent even as digital effects gained ground. Today, many productions blend both approaches, but Burke's films remain a masterclass in why practical makeup still matters for performance and texture.

Final note

Michèle Burke's passing marks the loss of a relentless craftsman whose fingerprints are on some of cinema's most recognizable faces. She trained her eye on actors and characters, then used color, prosthetics and restraint to reveal deeper truths about them. For filmmakers and fans who value the tactile, human side of movie magic, her work will continue to instruct and inspire for years to come.

Source: deadline

Leave a Comment