9 Minutes

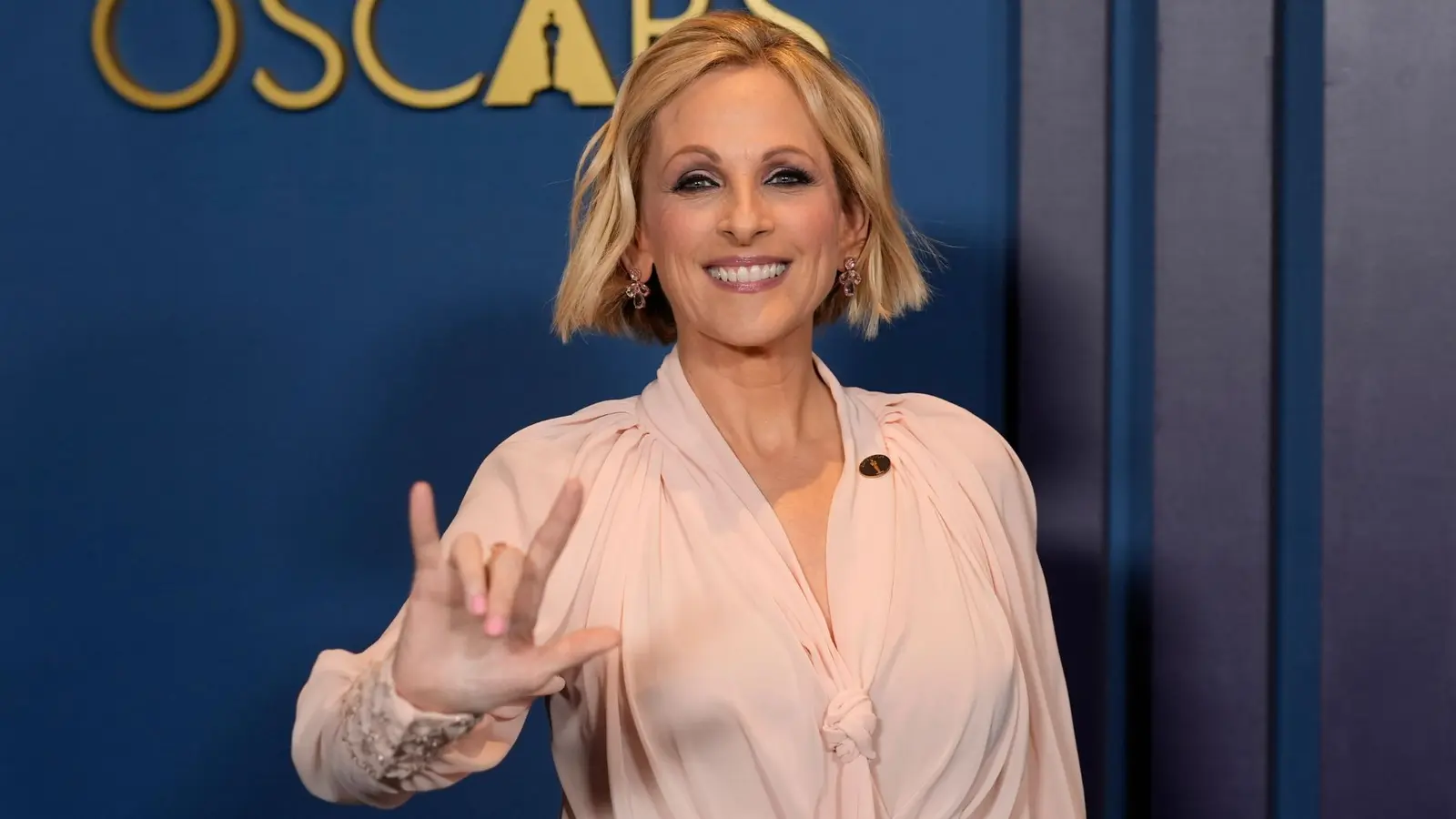

When Marlee Matlin agreed to let filmmakers chronicle her life, she laid down one non-negotiable condition: the director must be Deaf. That demand shaped every choice behind Marlee Matlin: Not Alone Anymore, a documentary that treats intimacy, memory and representation with a deliberate, deaf-centered craft. The result is not only a portrait of an Oscar-winning performer and activist, but also a manifesto for how to make films about marginalized lives with dignity and nuance.

Shoshannah Stern — a Deaf actor, writer and now director — was Matlin’s pick. Stern had looked up to Matlin since childhood: Matlin’s breakthrough performance in Children of a Lesser God made her the first Deaf performer to win an Academy Award and offered an image that many Deaf viewers could finally recognize themselves in. That formative admiration became an asset; Stern brought a fan’s knowledge and a peer’s empathy. She could point archivists precisely to interviews and gestures that mattered, not merely for their star power but for what they signified to Deaf audiences.

Producer Justine Nagin framed Stern’s appointment as both practical and emotional: Matlin saw in Stern the strength of her writing and the capacity to hold difficult moments. The creative shorthand that exists between two artists who share similar lived experiences allowed the film to attempt a rare level of trust.

On-camera intimacy: the couch as a practice

One of the documentary’s most striking formal choices is its recurring image of Matlin and Stern on a couch — feet up, close, conversing rather than interrogating. Stern insisted from the outset that these exchanges be conversations, not interviews, giving Matlin the autonomy to steer the narrative. That decision matters on camera: seeing two Deaf women constructing memory in real time reverses the usual documentary dynamic where an outsider extracts trauma for the viewer’s consumption.

Stern described the couch as a practical and symbolic measure: “I’m feeling what she’s feeling,” she explained. The effect is visceral. The viewer is invited into a private space where consent, both emotional and cinematic, is continually negotiated. For documentary fans, it’s a reminder that method matters — that style can be ethics.

Facing pain on her own terms

Matlin’s career has always carried a double burden. After winning the Oscar at 21, she was suddenly cast — by industry and public alike — as the spokesperson for the Deaf community. The film lets her explore that pressure honestly: the loneliness of being the “first,” the cost of visibility, and the complicated aftermath of fame.

Crucially, the documentary also gives Matlin space to confront a fraught chapter of her personal life: her relationship with William Hurt, whom she met on Children of a Lesser God. Hurt famously handed her the Best Actress envelope at the Oscars, and Matlin has alleged abuse in past memoirs. The film allows her to address this history on her own terms, contextualizing it within larger conversations about domestic violence and the ways that Deaf women are uniquely vulnerable. Stern, who shared her own survivor experience, carefully situates Matlin’s testimony within generational change: the vocabulary and public accountability of the #MeToo era did not exist for Matlin when she first told her story.

Sound, or the lack of it: design as empathy

One of the most talked-about technical achievements in the film is its immersive sound design. The creative team enlisted Skywalker Sound and received a Dolby grant to craft mixes that let hearing viewers inhabit Matlin’s sonic world. In some couch conversations the choice is radical — there is almost no conventional sound, save for the rustle of breaths and the ambient noise of hands signing. In scenes with Matlin’s extended, hearing family, the mix tilts the way a cutting-room argument would: overlapping chatter, heard but not intelligible, locates us in Matlin’s experience of being left out.

This use of sound is both an aesthetic gesture and an accessibility commitment. It refuses to translate every utterance, instead sometimes insisting that viewers negotiate absence the way Matlin has for decades. It’s a technique that aligns this film with other recent works exploring sensory perspective — from the tactile intimacy of some contemporary arthouse films to the way CODA flipped assumptions about access and voice.

Comparisons and context

Comparisons to Children of a Lesser God are inevitable, but this film is less about rehashing a landmark role than about reexamining the costs of being that role. Where the 1986 feature brought Deaf presence to mainstream narrative cinema, Not Alone Anymore interrogates the human fallout behind such milestones.

The film also arrives in a richer ecosystem of Deaf-led storytelling. Troy Kotsur’s Best Actor win for CODA signaled that the Academy was finally recognizing Deaf performers again — and that Matlin did not have to be the only name in that history anymore. Alongside CODA and recent Deaf creatives’ rising profiles, this documentary participates in a growing trend: the push for authentic storytellers behind the camera as well as in front of it.

Behind-the-scenes and production notes

The filmmakers leaned on archivists, editors and an empathetic post-production team. Editor Sara Newens and lead producer Robyn Kopp worked closely with Bonnie Wild at Skywalker. The Dolby grant helped pay for an immersive mix that the team says lingers with audiences. During a shoot in Chicago, Stern and the crew carefully staged family interactions to balance respect for Matlin’s relatives with the film’s thematic goals — a tightrope walked with sensitivity.

Critics and community reaction

Early festival screenings and the documentary’s inclusion in discussions like Deadline’s For the Love of Docs series have prompted strong reactions. Deaf communities have been especially vocal: many praised the film for its centering of Deaf authorship and for the way it reframes Matlin’s narrative beyond celebrity. Some critics, however, raised questions about the ethics of representing trauma on film and whether documentary teams can ever fully insulate subjects from the public consequences of disclosure. That debate is an important part of the film’s afterlife: how to tell hard stories without exploiting them.

A critical perspective

It’s worth noting that the film’s greatest achievement is also its most modest: it doesn’t try to be an exhaustive biography. It’s a curated conversation, intentionally partial — and that partiality is framed as a virtue. By refusing to exoticize Matlin’s Deafness, the film instead places it in a continuum: a child’s fan memory, a mid-career crisis of expectation, an elder’s quiet reckoning. The documentary’s restraint is its argument: being seen fully requires time, consent and the right company.

Expert view

"Not Alone Anymore demonstrates how authorship changes the story you’re allowed to tell," says film critic Anna Kovacs. "Stern’s perspective reshapes archival moments into emotional truth, not just biographical footnotes. The film is both a corrective and an elegy for the loneliness that accompanies being 'first.'"

Why this matters for cinema

This documentary contributes to an industry-wide conversation about representation on and off camera. It argues that authenticity is not merely casting Deaf actors but also placing Deaf directors, editors and sound designers at the center of production. As streaming platforms and festivals continue to amplify diverse voices, films like Not Alone Anymore set a blueprint: give subjects sovereignty, design access into the form, and let marginalized artists tell their own stories.

For viewers who love movies and care about equity in the arts, this film offers both pleasure and provocation. It’s a reminder that the language of cinema — framing, sound, editorial rhythm — can be remade to reflect a broader range of human experience. In doing so, it enlarges what mainstream audiences expect from documentaries about identity, fame and survival.

Short note on legacy

Marlee Matlin’s life is emblematic of both the breakthroughs and the burdens of representation. Not Alone Anymore doesn’t claim to settle all debates about representation or trauma; it offers instead a model of care. By centering Deaf authorship and prioritizing consent, the film shows how documentary can be a space of repair as much as revelation.

If you follow awards season, disability representation, or documentary craft, this is a film to watch — not only for its subject, but for its method.

Source: deadline

Leave a Comment