5 Minutes

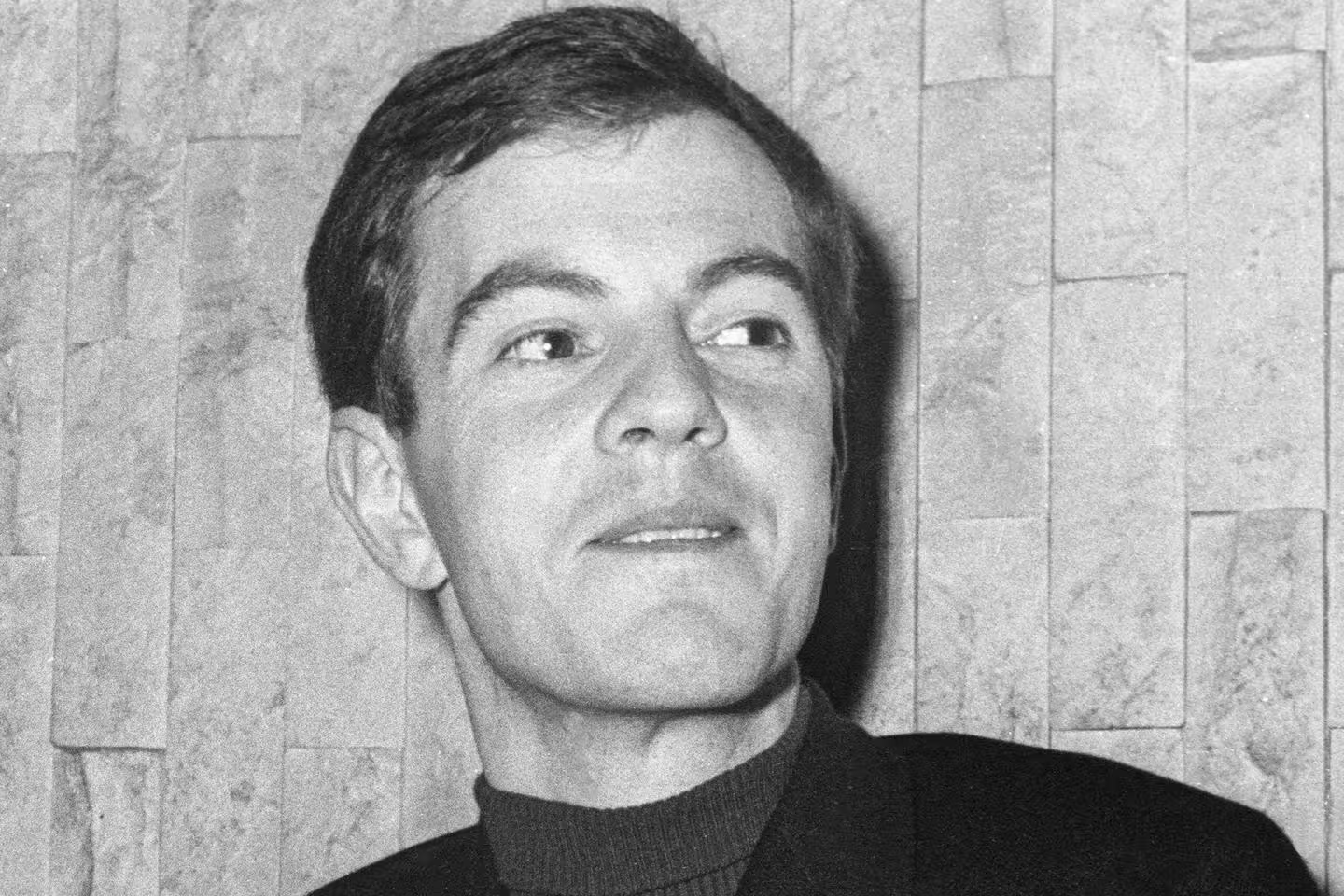

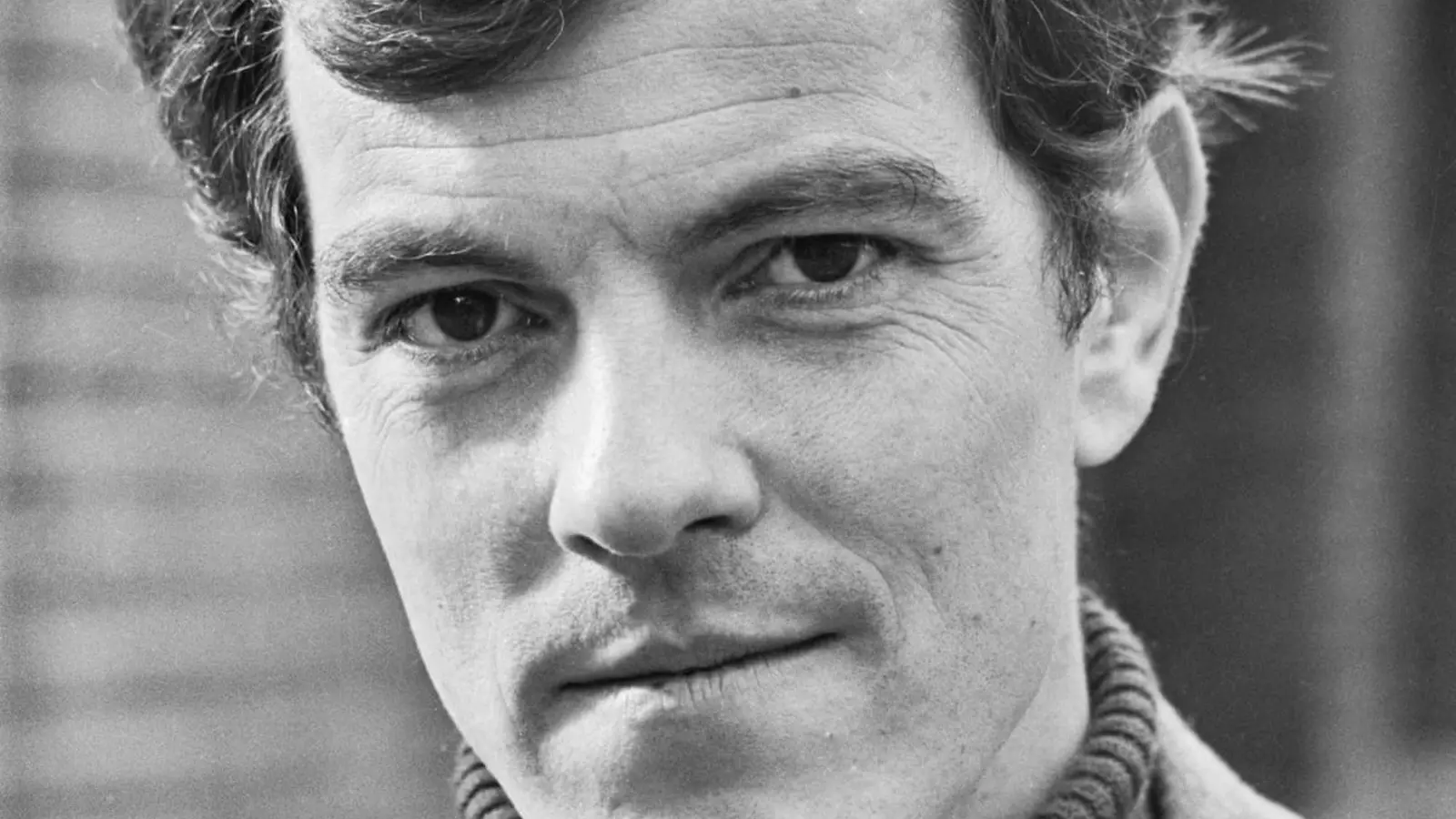

Peter Watkins, a voice that refused to be silenced

Peter Watkins, the dissenting British filmmaker whose uncompromising docudramas reshaped how television and cinema could alarm and educate audiences, has died at 90. His family confirmed he passed away in a hospital in Bourganeuf, central France, where he had lived for the past 25 years. For generations of viewers, Watkins was less a conventional director than a civic provocateur — using documentary techniques, non‑actors and staged realism to confront viewers with political truths they might rather avoid.

Watkins’s best-known work, The War Game (1965), remains a touchstone. Conceived as a quasi-documentary about a nuclear strike on the English city of Canterbury, it was famously withheld from broadcast by the BBC for two decades; the corporation judged it "too frightening" for public viewing. The film nevertheless won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 1967 and continues to be cited alongside later nuclear dramas such as Threads (1984) for its harrowing, documentary-style realism. American critic Roger Ebert called some sequences "among the most terrifying in film history," and viewers still report the same stunned silence after a first viewing.

Career highlights and an adversarial relationship with the BBC

Watkins began with shorts and topical documentaries — his Faces of Forgetting about the Hungarian uprising drew early attention — before joining the BBC in 1962. The Battle of Culloden (1964) used non‑professional actors and a reporter’s immediacy to recast a historical event as contemporary reportage, influencing later docudramas and historical reconstructions for TV.

After the BBC’s decision on The War Game, Watkins turned outward, making films abroad and embracing projects that interrogated media, power and spectacle. Privilege (1967) explores pop stardom as state propaganda. Punishment Park (1971), his controversial examination of political repression and ritualized violence set in an America that stages a “game” to hunt dissenters, remains unsettling for its ethical provocations and prescient in its questions about state power and spectacle.

Watkins’s Edvard Munch, a four‑hour cinematic study of the Norwegian painter, was broadcast in Norway and later screened in cinemas; The Guardian lauded it as "a four‑hour film of extraordinary beauty." During later decades he produced sprawling works in Scandinavia, including Free Thinker (about August Strindberg) and the 873‑minute Journey (1983–87), which is often cited as the world’s longest non‑experimental documentary, investigating public attitudes toward nuclear arms.

Beyond awards and controversy, Watkins’s methods mattered: nonlinear timelines, handheld cameras, and the use of everyday people as carriers of political freight made his films feel palpably immediate. His distaste for sanitized television narratives and centralized media power led him to say that he spent decades trying to shift the balance of influence from the broadcasters back to ordinary people.

"Watkins’s work forced television to reckon with moral responsibility," says cinema historian Anna Kovacs. "He refused to let viewers stay comfortable. Even when his films were banned or marginalized, they incubated a different public language for political cinema."

Watkins’s final film, Commune (2000), revisited the Paris workers’ uprising of 1871 in a televisual form that underlined his lifelong preoccupation with popular revolt and historical memory.

Trivia and legacy notes: many film students point to Watkins’ use of non‑actors and improvised dialogue as a precursor to later mockumentary and reality‑TV aesthetics. His disputes with establishment broadcasters also helped fuel debates about censorship, public-service broadcasting and the duties of documentary filmmakers.

Watkins remains a polarizing figure: admired by critics and film historians for daring and craft, criticized by some for didacticism or moral bluntness. Yet his influence on documentary drama, political cinema and the aesthetics of televised realism is indisputable.

In an era when streaming platforms and documentaries continue to test the boundaries of politics and entertainment, Watkins’s films are essential viewing: reminders that form and ethics can be weaponized to awaken public conscience.

Comments

Marius

Is it true BBC banned The War Game for 20 years? feels like modern platforms would never hide that now, right? hmm.

atomwave

wow didn't expect that. his War Game still floors me, silent in the room, then anger. visceral, needed.

Leave a Comment