9 Minutes

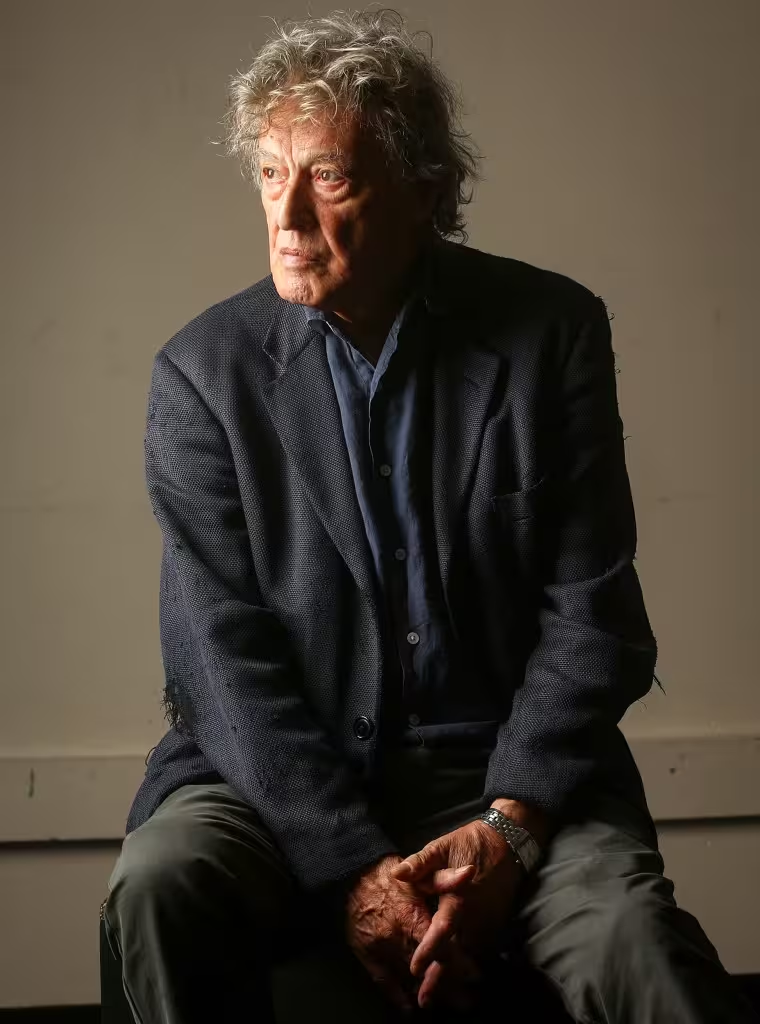

Tom Stoppard: A Life in Language and Drama

Tom Stoppard, the quietly revolutionary playwright and Oscar-winning screenwriter whose razor wit reshaped modern theatre and left an indelible mark on film, has died at 88. Stoppard passed away peacefully at his Dorset home, surrounded by family. Across stagehouses, film festivals and classrooms, the name Stoppard became shorthand for verbal virtuosity, philosophical rigor and the rare ability to make ideas sing.

Born in Zlín, Czechoslovakia, Stoppard’s early life was shaped by dislocation. His Jewish family fled the Nazi invasion in 1939 and eventually reached England by way of Singapore and Bombay. That childhood of exile and cultural translation would seep into his lifelong preoccupations: identity, belonging, political conscience and the precarious comedy of being human.

From Fringe Breakthrough to Theatrical Icon

Stoppard exploded onto the British theatre scene in 1966 with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, a daring, metafictional riff on two minor characters from Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Initially a hit at the Edinburgh Fringe, the play quickly moved to the Old Vic and then Broadway, earning Stoppard his first Tony in 1968. The success of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern announced a singular voice: playful, erudite, and endlessly curious about the mechanics of language.

Through the 1970s and 1980s Stoppard continued to blend intellectual play with theatrical craft. Works like Jumpers and Travesties mixed philosophy, history and satire; The Real Thing (1982) revealed a new emotional depth, prompting critics to reassess the balance between Stoppard’s cleverness and feeling. Arcadia (1993) further fused science, romance and poetic observation; it remains a touchstone in contemporary drama syllabi.

Major Achievements and Awards

Stoppard’s trophy cabinet was extraordinary: four Tony Awards for plays spanning Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, Travesties, The Real Thing and the expansive trilogy The Coast of Utopia; an Academy Award for his screenplay for Shakespeare in Love; and lifetime honors such as the Writers Guild Laurel Award. The Coast of Utopia — a nine-hour trilogy about Russian intellectual life in the 19th century — proved his appetite for ambitious theatrical architecture, and won the Tony for Best Play after its Olivier run.

Stagecraft, Politics and the ‘Stoppardian’ Mind

Critics sometimes used the term 'Stoppardian' to describe work that uses witty, philosophical comedy to probe deeper truths. Early detractors accused him of prioritizing cleverness over social engagement, but as his career progressed, Stoppard layered moral urgency and human vulnerability into his verbal bravura. Plays like Every Good Boy Deserves Favour and Rock ’n’ Roll show his political commitments — from Soviet dissidence to Czech resistance — while works such as The Real Thing and Invention of Love expose the playwright’s surprising tenderness.

Industry observers point out that Stoppard’s influence extends beyond content to craft: his plays remodeled how dialogue can carry both argument and emotion. In an era when British theatre moved between kitchen-sink realism and postmodern experimentation, Stoppard carved out a distinct path, pairing intellectual density with theatrical accessibility.

Transition to Screen: Adaptations and Original Films

Stoppard’s voice translated to the screen with mixed but often brilliant results. He co-wrote Terry Gilliam’s surreal Brazil (1985) and adapted J.G. Ballard for Steven Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun (1987). His collaboration with Marc Norman on Shakespeare in Love earned him an Academy Award and brought his taste for theatrical metafiction to mainstream cinema — a romantic, witty reimagining of Elizabethan backstage life that resonated with awards bodies and audiences alike.

Beyond credited work, Stoppard served as a sought-after script doctor in Hollywood, reportedly polishing scripts from Indiana Jones to Star Wars: Episode III — Revenge of the Sith. Such behind-the-scenes contributions speak to his reputation as a fixer of narrative and dialogue, even on projects very different from his stage fare.

TV and Mini-Series: Parade’s End and Beyond

In the 2010s, Stoppard brought literary adaptation to prestige television with Parade’s End, an HBO/BBC miniseries adapted from Ford Madox Ford’s novels and starring Benedict Cumberbatch. The series, widely praised for its fidelity and cinematic ambition, showcased Stoppard’s skill at translating complex literary voice into screen drama.

He also adapted Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina into a 2012 film that polarized critics for its stylized, stage-like approach — a bold experiment that underscored Stoppard’s willingness to play with form rather than simply reproduce classic texts.

Comparisons and Context

Comparative perspectives help place Stoppard in theatre and film history. Unlike contemporaries such as Harold Pinter, whose silences and menace defined his aesthetic, Stoppard’s theatre often revolved around linguistic excess and intellectual jousting. Compared with playwrights focused on social realism, Stoppard’s work felt more cosmopolitan and intertextual — closer in spirit to Luigi Pirandello or Tom Stoppard’s own playful forebears, while still uniquely modern.

On the cinematic side, Shakespeare in Love sits alongside other meta-Hollywood films that celebrate and interrogate the past — think The Artist’s tribute to silent cinema or Shakespeare adaptations that reframe canonical texts for new audiences. Stoppard’s screenplays favored theatrical conceits adapted for cinema’s visual demands, a balancing act that sometimes delighted and sometimes divided critics.

Criticism, Evolution, and the Human Core

Not all commentators were unreserved in their praise. Some early critics dismissed Stoppard as a dazzling showman whose verbal pyrotechnics left characters underwritten. Over time, however, many reassessed their view as plays like The Real Thing and Arcadia displayed genuine emotional stakes. New York Times critic Ben Brantley observed that Stoppard’s later plays sometimes risked letting ideas overwhelm character, a tension that remained part of his dramatic signature.

Still, friends and colleagues frequently praised his humanity. United Agents summed up his artistic legacy: brilliant, irreverent, generous in spirit and deeply in love with the English language.

Behind the Scenes and Lesser-Known Facts

- Stoppard often revisited political themes connected to his Czech roots; Rock ’n’ Roll intersects music and dissent across decades of Czechoslovak history.

- His 1990 screen adaptation of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern won the Golden Lion at Venice, underscoring his ability to move between mediums.

- He worked uncredited on major studio projects, helping reshape scripts in Hollywood’s biggest franchises.

- The term 'bounced Czech' was Stoppard’s own playful riff on his exile and reinvention as an English artist.

What Critics and Admirers Say

Film historian Marko Jensen offers a concise appraisal: "Stoppard rewired what stage writing could be, marrying philosophical daring with theatrical joy. His screen work brought that same intelligence to movies and television without ever abandoning his love of language."

This kind of verdict captures the paradoxical balance at the heart of Stoppard’s career: an unyielding cerebral appetite offset by an unmistakable tenderness for human contradiction.

Legacy for Theatre and Screenwriters

Stoppard’s influence is visible in contemporary playwrights and screenwriters who mix genre, history and theory — writers who treat dialogue as both argument and revelation. The adjective 'Stoppardian' endures as a shorthand for intelligent, witty drama that uses comedy to explore philosophical problems.

For filmmakers, his career demonstrates a creative route between theatre and film: adaptations need not be literal translations; they can be reinventions that respect source material while embracing cinema’s distinct language. Stoppard’s highs and experiments offer a roadmap for writers who want to bring literary rigor to popular formats.

A Personal Note

Stoppard’s personal story — refugee child turned English dramatist — is woven into his work in subtle ways. He rarely centered autobiography explicitly, insisting that personal truth leaks into work without authorial collusion. Yet his preoccupations with exile, identity and moral choice feel autobiographical in their emotional logic.

He is survived by his wife, Sabrina Guinness, and his four sons, including actor Ed Stoppard and the digital artist Barny Stoppard. The theatre and film worlds will remember him not only for awards and accolades but for the way his sentences could surprise and console at once.

In an era hungry for voices that can combine intellect with heart, Tom Stoppard leaves a body of work that will continue to be staged, studied and adapted. His plays and screenplays remain invitations to think, laugh and feel — a rare and enduring gift.

Source: variety

Comments

bioNix

Stoppard was brilliant, but sometimes ideas crowd the people onstage. still, Arcadia hits different, if that’s real then...

vibe.lt

is it true he worked uncredited on star wars? sounds like hollywood myth, anyone got receipts??

atomwave

wow, didn't expect to feel this sad reading his life. Language was his superpower, truly. RIP but what a legacy, those plays shaped me in college

Leave a Comment