4 Minutes

Unveiling a Surprising Connection: Oral Bacteria and Alzheimer’s Disease

Recent advances in neuroscience and microbiology have put forward an unexpected hypothesis about Alzheimer’s disease: instead of being solely a disease of aging neurons and genetics, Alzheimer’s may partly originate from infectious processes—specifically, from bacteria residing in our mouths. This emerging theory, supported by several scientific studies, is challenging traditional thinking about one of the world’s most prevalent neurodegenerative conditions.

The Scientific Background: Alzheimer’s Disease and Its Mysterious Causes

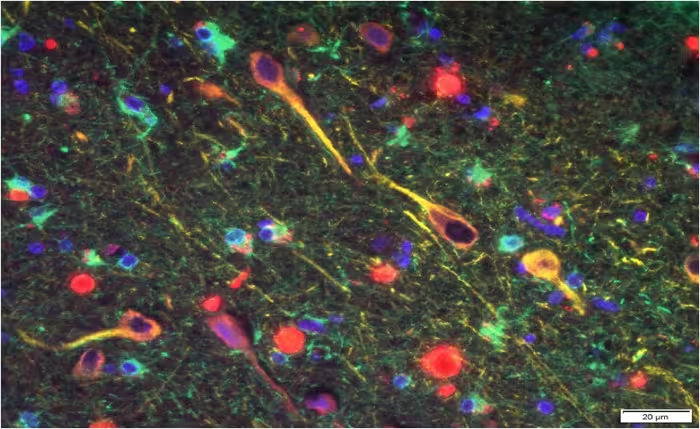

Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, has long been associated with the accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and tau protein tangles in the brain. While age and genetics remain key risk factors, the exact triggers that initiate these destructive processes are not fully understood. Intriguingly, mounting evidence now points to infections as potential contributors to Alzheimer's, intensifying the search for previously overlooked causes.

The 2019 Breakthrough: Linking Gum Disease to Alzheimer’s

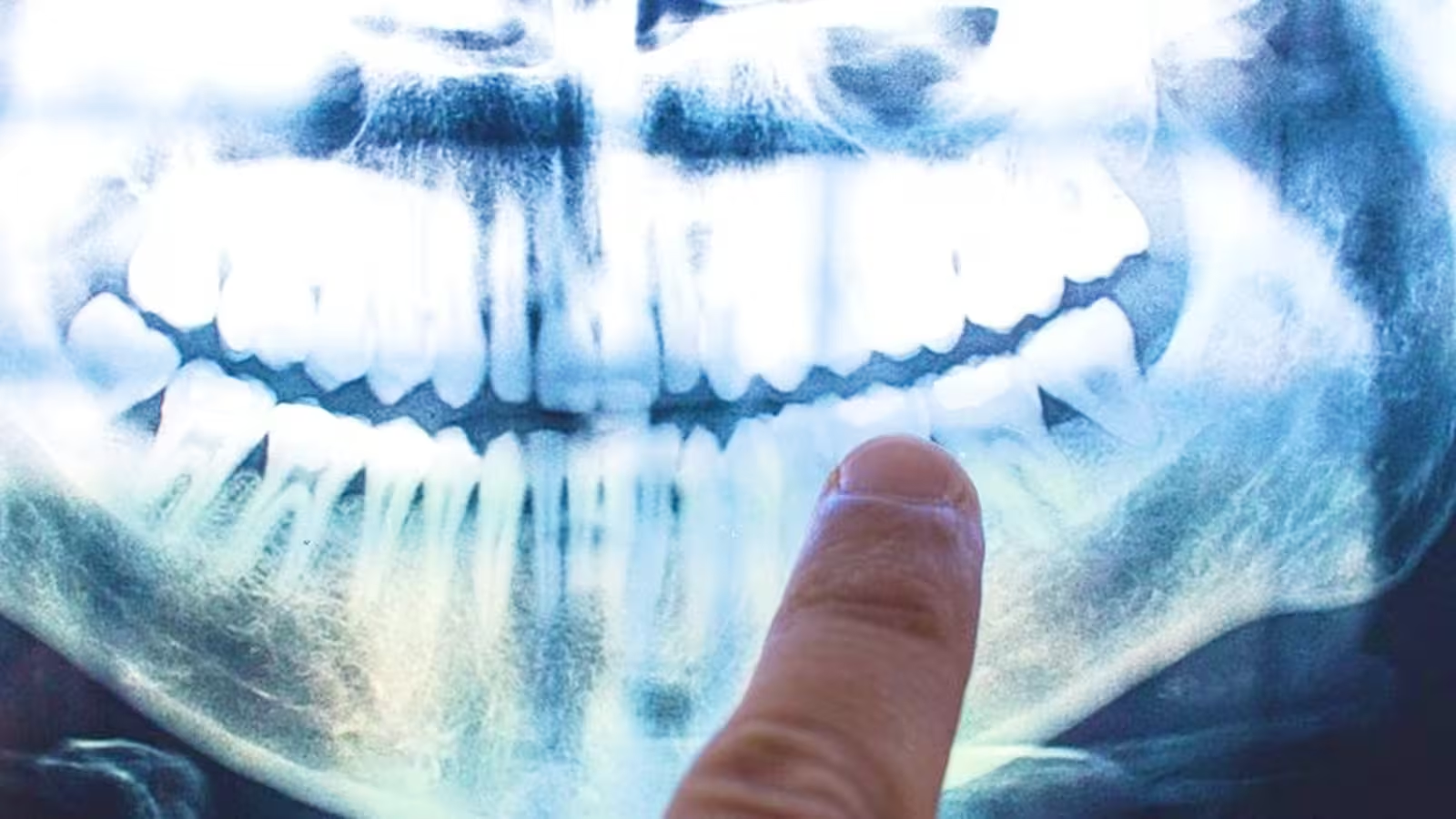

In a landmark 2019 study, a research team led by Dr. Jan Potempa, a microbiologist from the University of Louisville, identified the bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis—the primary agent behind chronic periodontitis (commonly called gum disease)—in the brain tissues of deceased patients who had Alzheimer’s disease. This finding added new weight to the theory that an underlying infection could play a role in the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s.

While earlier research had hinted at a correlation between poor oral health and dementia, Dr. Potempa’s team went further. In their experiments, healthy mice were orally infected with P. gingivalis. Results showed not only that the bacteria infiltrated the mice’s brains, but also that this brain colonization triggered increased production of amyloid beta proteins, hallmark biomarkers of Alzheimer’s pathology.

The Role of Cortexyme and the Discovery of Gingipains

This pioneering research was conducted in collaboration with Cortexyme, a biotechnology company co-founded by Dr. Stephen Dominy. The team’s investigations revealed that P. gingivalis releases toxic enzymes, known as gingipains, in the brain. These enzymes were detected in people who had Alzheimer’s, as well as in those with Alzheimer’s-related brain changes—even if they had never been diagnosed with dementia. This suggests that infection by P. gingivalis and its gingipains can be an early event, possibly preceding observable cognitive decline by many years.

As the authors noted: “Our identification of gingipain antigens in the brains of individuals with Alzheimer’s pathology, even without clinical dementia, suggests brain infection by P. gingivalis is not simply a side effect of poor oral care due to existing dementia, but may be a trigger occurring before symptoms emerge.”

Therapeutic Implications and Future Research Directions

In addition to their compelling findings, the researchers tested a candidate drug called COR388, designed to inhibit gingipain activity. In mice, treatment with COR388 reduced P. gingivalis levels in the brain, lowered amyloid beta production, and decreased inflammation in neural tissues. While these results are preliminary and limited to animal models, they raise hope for new therapeutic approaches targeting the bacterial mechanisms linked to neurodegeneration.

The Alzheimer’s research community is approaching these discoveries with cautious optimism. Dr. David Reynolds, chief scientific officer at Alzheimer’s Research, commented, “Drugs targeting the bacteria’s toxic proteins have so far only shown benefit in mice, yet with no new dementia treatments in over 15 years it’s important that we test as many approaches as possible to tackle diseases like Alzheimer’s.”

Looking Ahead: Rethinking Prevention and Early Detection

These revelations underscore the critical importance of oral health—not just for teeth and gums, but potentially for lifelong brain health. If a causal relationship between P. gingivalis and Alzheimer’s is confirmed in humans, regular dental care and early intervention against gum disease may play a more vital role than ever suspected in reducing dementia risk.

However, experts caution that while the presence of bacterial markers in the brain is highly suggestive, it does not yet amount to definitive proof of causation. It’s also not yet known whether preventing or treating gum disease can halt or reverse the progression of Alzheimer’s in people.

Ongoing clinical trials and future research are needed to explore how this brain–mouth axis might be exploited for early diagnosis, prevention, and new treatments for neurodegenerative disease.

Conclusion

The emerging link between gum disease and Alzheimer’s disease represents a significant shift in our understanding of dementia’s origins. The discovery of oral bacteria and their toxic proteins in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients opens new avenues for scientific exploration and potential breakthroughs in treatment. As researchers continue to investigate, maintaining good oral hygiene may not only protect your smile—it could also prove crucial in safeguarding your brain’s health for the long term.

Source: dx.doi

Comments