6 Minutes

Introduction: Unveiling the Secrets of Sauropod Diets

For more than a century, sauropod dinosaurs — the iconic long-necked herbivores such as Brontosaurus and Brachiosaurus — have captured scientific and popular imagination. Paleontologists have widely accepted these prehistoric giants as strict plant-eaters, yet concrete evidence directly confirming their dietary habits had eluded researchers. That has now changed, thanks to an extraordinary find in the Australian outback: the fossilized remains of a sauropod known as "Judy," complete with her last meal preserved within her abdominal cavity. This discovery is not only the first of its kind in Australia, but it also provides unprecedented insights into the feeding behaviors and dietary adaptations of the largest terrestrial animals to walk the Earth.

Background: Sauropod Evolution and Anatomy

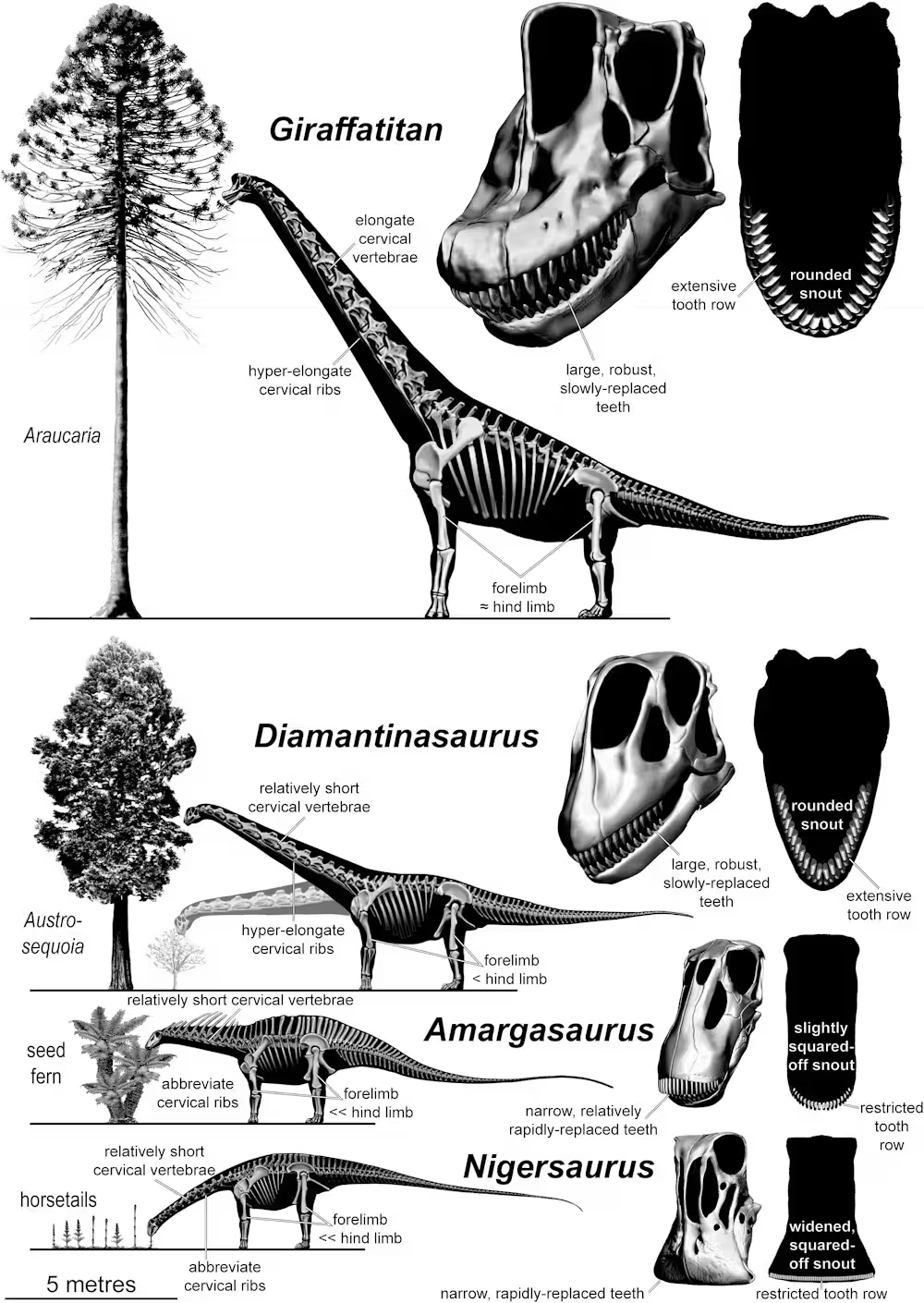

Dominating ecosystems throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, sauropod dinosaurs represented a flowering of herbivorous megafauna. Over a span of 130 million years, they shaped landscapes across ancient continents. Despite their uniform reputation as colossal, four-footed plant browsers with elongated necks and relatively simple teeth, sauropods diversified in important anatomical ways. While most exhibited robust bodies, varied neck flexibility, and different snout and tooth adaptations, these differences influenced which plants they could access and how efficiently they could consume them. Some species had squared, narrow snouts with quickly replaced teeth, conducive to cropping soft foliage, while others bore rounded jaws with sturdier teeth extending further back. Neck lengths could range up to 15 meters, shaping feeding height and dietary strategy. To sustain their massive frames — some exceeding 70 tons — sauropods required vast quantities of vegetation each day.

The Landmark Discovery of "Judy"

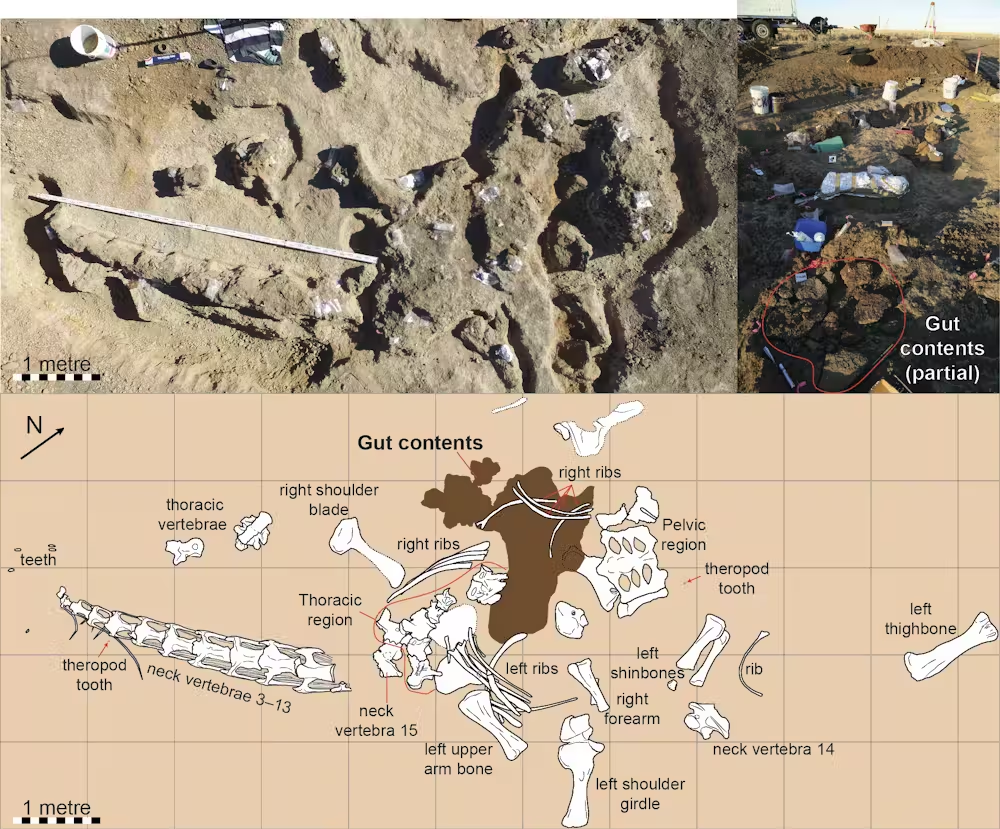

Until recently, the widely held image of the sauropod as a plant-eater rested largely on circumstantial evidence: blunt teeth unsuitable for predation, limited brainpower contrasting with active hunters, and fossilized trackways showing slow, heavy movement. It was not until the 2017 excavation led by the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum in Winton, Queensland, that the first direct evidence surfaced. Paleontologists unearthed "Judy," a 95-million-year-old sauropod recognized as the most complete specimen — and the only one with preserved fossilized skin — ever found in Australia.

During preparation of Judy’s fossil, researchers identified a distinct, plant-rich layer within the abdominal region: a dense, two-square-meter rock deposit, approximately ten centimeters thick, brimming with fossil plant material. Crucially, its confinement inside the boundaries of Judy’s fossilized skin strongly suggested these were gut contents, offering a rare glimpse of the sauropod’s final meal.

Advanced Scientific Analysis

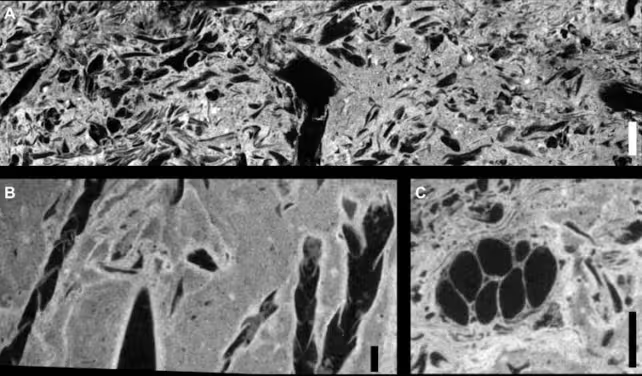

To analyze this precious evidence, experts employed cutting-edge X-ray and neutron scanning technologies at Australian scientific facilities, including the Synchrotron in Melbourne, CSIRO in Perth, and ANSTO in Sydney. These non-destructive imaging techniques allowed researchers to digitally reveal the shapes and structures of preserved plant remains hidden within the rock, while selective sampling enabled chemical and mineralogical study. Results showed that microbial activity in an acidic environment, likely caused by digestive juices, had fossilized the plant material after Judy's death. The minerals that replaced the soft tissues were derived in part from the dinosaur’s own decomposing body.

Key Findings: What Judy Ate and How Sauropods Fed

Judy’s gut contents confirmed several longstanding hypotheses while adding new layers of understanding to sauropod ecology. Analysis identified a diverse plant-based diet: bracts from ancient conifers (related to modern monkey puzzle trees and redwoods), seed pods from now-extinct seed ferns, and leaves of angiosperms (flowering plants) — a group then in the early stages of evolutionary expansion. This varied menu demonstrates both vertical and horizontal feeding strategies.

The presence of conifer bracts, which would have grown high above ground level, aligns with previous interpretations that Diamantinasaurus (Judy’s species) browsed at elevated heights using its long neck. Contrastingly, angiosperms at the time typically grew as lower shrubs or groundcover, indicating Judy also fed closer to the forest floor. Notably, Judy was not fully mature when she died, suggesting that feeding behaviors and dietary preferences may have shifted as individuals aged, with younger sauropods making greater use of low-growing vegetation. Regardless of age, the discovery confirms that sauropods were lifelong vegetarians, relying on vast amounts of plant matter to fuel their bodies.

Interestingly, the fossil record reveals that sauropods did not thoroughly chew their food. Instead, they relied heavily on gut fermentation and microbes to break down fibrous plant material, a process similar to that seen in some modern herbivores such as cows. The mechanical and chemical breakdown took place almost entirely within their voluminous digestive tract.

Broader Implications and Future Prospects

The preservation of both soft tissue and direct gut contents in Judy opens up fertile ground for future research. Such discoveries are rare but invaluable, as they enable scientists to reconstruct ancient diets and ecological relationships with far greater precision. The techniques used in this study — advanced imaging, chemical analysis, and comparative anatomy — set a new standard for paleontological research not only in Australia but globally.

Beyond enhancing our knowledge of sauropod biology, studies like this inform debates on dinosaur metabolism, growth rates, migration patterns, and their interactions with evolving plant communities during the Mesozoic era. As new finds from sites like the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum emerge, researchers will continue to refine our understanding of how Earth's prehistoric giants survived and thrived for millions of years.

Today, Judy’s fossilized skeleton, skin, and gut contents are on public display at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum in Winton. This remarkable exhibit serves not just as a window into a lost world but as a symbol of science’s relentless drive to uncover the hidden stories of natural history.

Conclusion

The discovery of Judy's fossilized last meal provides the most direct evidence to date of sauropod feeding habits and dietary flexibility. Through a combination of state-of-the-art technology and classic field paleontology, scientists have revealed that these ancient giants employed a dynamic feeding strategy, consuming a range of plants from different heights and relying heavily on gut microbes for digestion. Such findings enrich our understanding of dinosaur biology and contribute vital data for reconstructing ancient ecosystems. As more discoveries come to light, the story of Earth's largest herbivores continues to evolve, inspiring both scientific inquiry and public fascination around the world.

Source: theconversation

Comments