5 Minutes

Uncovering Evolutionary Insights Through Tooth Enamel

Although tooth enamel might seem an unusual medium for studying human evolution, it serves as a valuable record of our ancient relatives and their lineage. A breakthrough study published in the Journal of Human Evolution reveals that small, shallow pits discovered in fossilized hominin teeth may not indicate illness or malnutrition, as previously assumed. Instead, these features could represent inherited evolutionary traits, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of human ancestry.

The Mystery of Uniform Enamel Pitting

For decades, scientists examining fossil teeth—predominantly from early human ancestors in Africa—believed these consistent, circular pits resulted from developmental stress, such as poor nutrition or disease during childhood enamel formation. However, a comprehensive survey of fossil teeth from both eastern and southern Africa challenged this view.

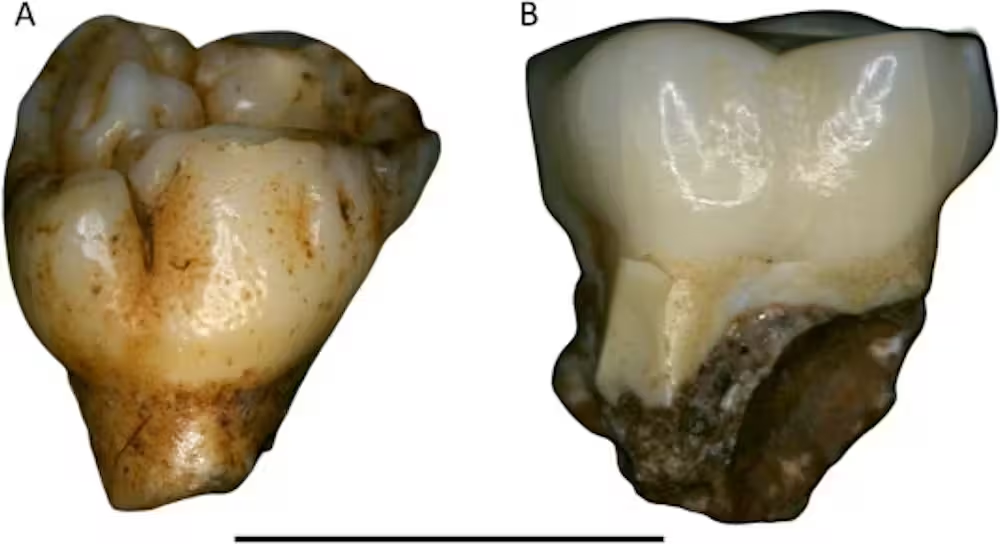

The shallow pits, first observed in Paranthropus robustus, a species closely related to modern humans, reveal remarkable uniformity. These pits are consistently circular, shallow, and often patterned together on the crown of the tooth. The latest research demonstrates they are present not only in Paranthropus robustus but also in eastern African Paranthropus boisei, as well as some early Australopithecus individuals—potential ancestors of both Homo and Paranthropus.

Beyond Defects: Patterns Across Millennia

Enamel pitting has traditionally been classified as a defect tied to stresses from early development. However, the regular shape and distribution of these pits, along with their occurrence across species, vast geographic regions, and a timespan exceeding two million years, hint they are far more than coincidental or pathological. The pits usually cluster in particular areas of the tooth crown and do not coincide with other signs of dental or systemic disease.

Mapping Evolutionary Branches Using Fossil Teeth

To trace the phenomenon, researchers examined teeth from hominin fossils spanning the Omo Valley in Ethiopia—a site chronicling over two million years of evolutionary history—and compared findings with teeth from key southern African sites such as Drimolen, Swartkrans, and Kromdraai. These collections span three major hominin genera: Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and Homo.

Their findings were profound: uniform enamel pitting recurs in Paranthropus from both East and Southern Africa, and in the oldest Australopithecus fossils from Ethiopia, dating to about three million years ago. Notably, this pattern is absent in southern African Australopithecus africanus and in every Homo specimen examined from these key sites, indicating a restricted evolutionary distribution.

Rethinking Dental Markers: Trait or Malfunction?

Were these pits caused by stress or disease, one would expect to see a relationship with tooth size, enamel thickness, and a spread across both front and back teeth. Yet, these factors show no strong correlation. Additionally, stress-related defects generally produce horizontal bands and impact all teeth developing at that period, unlike these isolated, uniform pits.

The pattern instead suggests a heritable genetic trait that may arise from differences in how enamel is formed. The evolutionary function of this trait, if any, remains undetermined, but it surfaces in ways consistent enough to signal a new marker for tracing hominin relationships.

Modern Comparisons: Amelogenesis Imperfecta and Evolutionary Significance

A rare genetic condition in modern humans, amelogenesis imperfecta, also produces enamel defects, usually affecting about one in every 1,000 people. However, the frequency and uniformity of pitting in ancient Paranthropus are far greater, seen in up to half of the individuals examined, making it unlikely to be the result of a pathological disorder.

Furthermore, amelogenesis imperfecta often leads to compromised dental health, whereas the ancient pits appear in otherwise robust teeth. This strengthens the argument that these shallow depressions may have held some evolutionary advantage or, at the very least, emerged as a neutral byproduct of genetic change as hominin species adapted to their environments.

Potential as an Evolutionary Marker

Subtle dental traits—such as enamel thickness, cusp patterns, or specific wear—are already invaluable to paleoanthropologists working to classify species and unravel evolutionary relationships. The identification of uniform pitting offers another powerful tool, particularly since its presence or absence divides closely related genera and lines up with emerging theories about hominin family trees.

For example, the persistence of enamel pitting in Paranthropus across geographic boundaries supports its status as a monophyletic group—that is, all its species descend from a single, recent ancestor, instead of arising independently from separate Australopithecus populations. The complete lack of pitting in over 500 teeth attributed to southern Africa's Australopithecus africanus, but not in older eastern African Australopithecus, points to a specific evolutionary moment or region where this trait may have originated.

Intriguing Outliers and Future Research Directions

The discovery raises questions about other unique hominins, such as Homo floresiensis—the so-called "hobbit" from Indonesia. Published images of their dental remains suggest similar pitting, potentially linking them to ancient Australopithecus branches rather than later Homo species. However, the same remains also display possible signs of disease, demanding more study before firm conclusions can be drawn.

To fully unlock the evolutionary significance of shallow enamel pitting, further research is needed, both to understand the genetic mechanisms behind its development and its functional or adaptive implications, if any. Notably, this trait is absent in modern Homo sapiens (apart from the rare cases of amelogenesis imperfecta) and other living primates, highlighting its unique place in the fossil record.

Conclusion

The discovery that shallow, uniform enamel pits are not merely signs of ancient disease or malnutrition but rather a likely inherited trait transforms them into a powerful tool for paleoanthropology. By tracking the presence of this subtle but consistent feature across fossil hominins, scientists gain a new method for mapping evolutionary relationships and investigating how early human lineages diverged. This finding enriches our understanding of teeth as not just tools for eating but as direct records of human evolutionary history, opening up exciting pathways for future genetic, developmental, and evolutionary research.

Source: theconversation

Comments