4 Minutes

Surgeons Pioneer Revival of Non-Beating Donor Hearts for Infant Transplantation

Scientific Context: Overcoming Barriers in Pediatric Heart Transplants

Pediatric heart transplantation remains one of modern medicine’s most challenging frontiers. In the United States, as many as 20 percent of infants awaiting heart transplants die before receiving a suitable organ, largely due to an extreme shortage of viable donor hearts. Traditional transplant protocols require donors to be declared brain dead, and only a tiny fraction—around 0.5 percent—of pediatric heart donations occur after what is known as circulatory death, where the heart and blood circulation have both ceased.

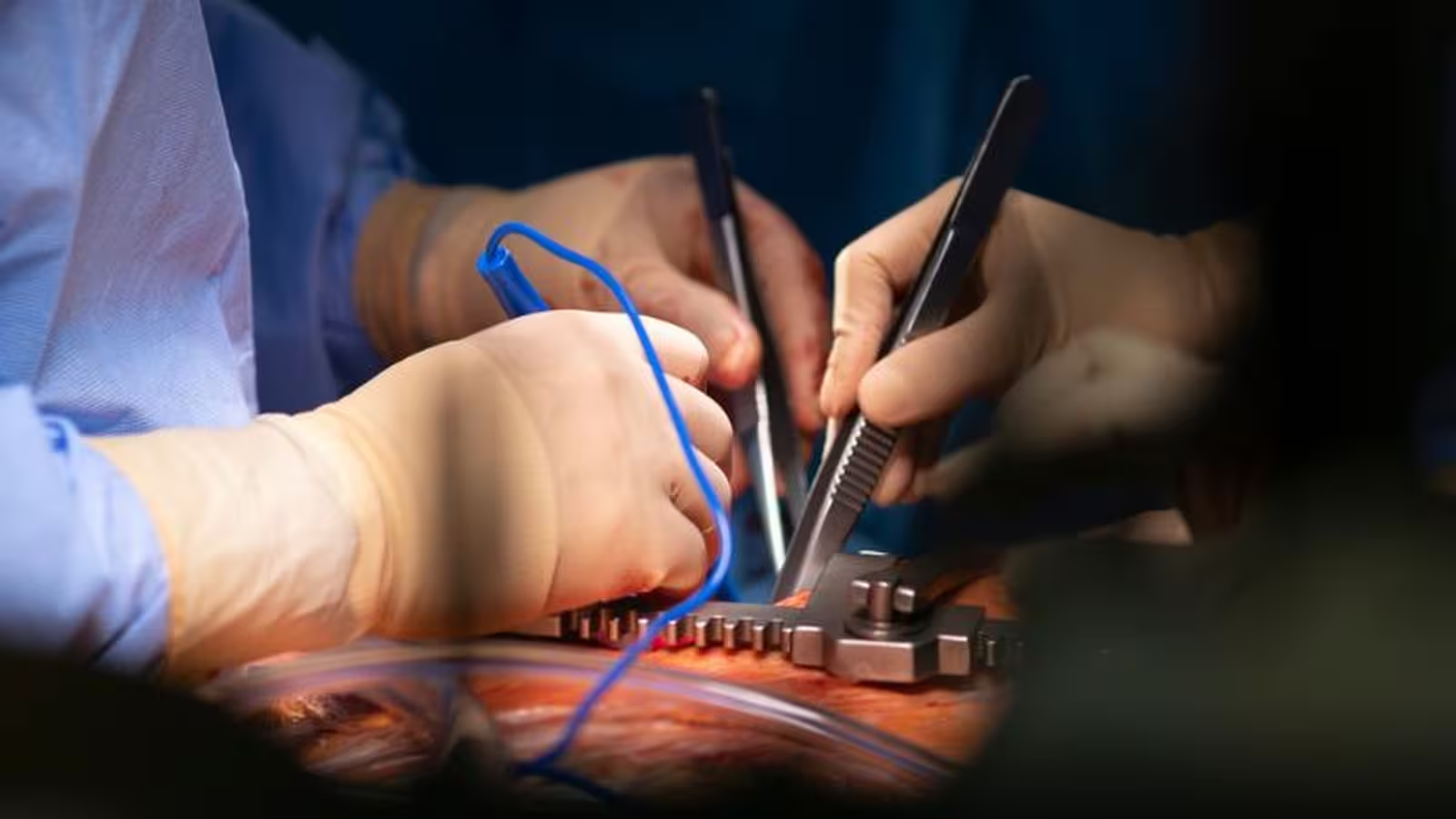

Groundbreaking Operation at Duke University: 'On-Table Reanimation' in Action

A surgical team at Duke University has achieved a breakthrough in pediatric cardiac medicine by successfully resuscitating a 'dead' heart on the operating table and transplanting it into a three-month-old infant. The donor heart had stopped beating for over five minutes—but with the consent of the donor’s family, surgeons utilized a custom-built system featuring an oxygenator, a centrifugal pump, and a blood reservoir to revive and support the infant-sized heart. This tailored machinery was essential, as standard organ care systems are often too large for neonatal organs. Following transplantation, the child showed normal heart function and no signs of organ rejection six months post-surgery, providing strong clinical evidence that 'on-table reanimation' can be a viable strategy for saving the youngest and most vulnerable patients.

Ethical Debates: Navigating Complex Moral Terrain

Transplant surgeons and ethicists have long debated the correct protocols for utilizing organs following circulatory death. Critics of resuscitating organs after death argue it may blur the critical definitions of death and raise concerns about the ethical removal of life support. Some fear restarting a heart in a donor’s body undermines the determination of circulatory death, thus crossing ethical lines. In contrast, Duke’s approach—reviving the heart externally, outside the donor’s body—has sparked interest for its potential to reduce these ethical dilemmas. Proponents estimate that expanding heart recovery methods to include circulatory death donations could increase the donor pool by up to 30 percent, drastically impacting pediatric survival rates.

Alternative Approaches: Vanderbilt’s Preservation-Based Method

While Duke’s team focuses on reanimation, researchers at Vanderbilt University are exploring technique variations that avoid immediate revival of donor hearts. Their innovative method clamps the heart’s circulation and uses a cold, oxygenated preservation solution to keep donor hearts viable for transplantation, while ensuring that no blood or perfusion reaches the brain. This approach intentionally avoids reanimation, minimizing ethical issues tied to definitions of death and organ retrieval.

Initial surgical outcomes using Vanderbilt’s method have been promising, with three successful infant heart transplants reported, each showing excellent early cardiac function. "Our technique flushes oxygenated preservation solution to the donor heart only, without reanimation and without systemic or brain perfusion," the Vanderbilt team explained in recent medical findings. They believe this preservation-based strategy could broaden the application of heart recovery from circulatory death donors far beyond pediatric cases.

Future Implications and Technological Innovation

Both on-table reanimation and advanced preservation technologies highlight the rapid evolution of transplantation science. They address pressing ethical, technological, and biological questions that have historically limited pediatric heart transplantation. As these innovations progress and clinical outcomes are monitored, the prospect of increasing the availability of life-saving organs for infants and children appears highly promising.

Conclusion

The successful revival and transplantation of a non-beating infant heart underscore remarkable advances in medical engineering, ethics, and pediatric care. Pioneering protocols from institutions such as Duke and Vanderbilt are expanding the donor pool and improving transplant outcomes while prompting important ethical conversations. Continued refinement of these techniques could transform pediatric organ transplantation, offering new hope for families and potentially saving thousands of young lives in the years ahead.

Source: nejm

Comments