5 Minutes

Archaeologists working at El Mirador cave in the Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain, have uncovered compelling taphonomic evidence that at least 11 people were processed and consumed in a single late Neolithic event roughly 5,709–5,573 years ago. The assemblage includes children and adolescents and displays a suite of modifications—cut marks, thermal alteration, smoothing of bone ends and punctures—consistent with systematic skinning, disarticulation, fracturing, cooking and consumption. Radiocarbon dating and isotopic work indicate these individuals were local and appear to have been butchered within the same narrow timeframe, suggesting a one-off episode rather than long-term funerary or subsistence cannibalism.

Archaeological context and scientific methods

The El Mirador bones were analyzed using standard archaeological and bioarchaeological techniques: macroscopic taphonomy, microscopic cut-mark analysis, radiocarbon dating, and strontium isotope ratios. Taphonomy is the study of processes that affect remains after death; here it distinguishes postmortem butchery and cooking from natural damage. Radiocarbon dating provides calibrated calendar age ranges, while strontium isotope analysis helps determine whether individuals were local or non-local by comparing ratios in bone to local geological baselines.

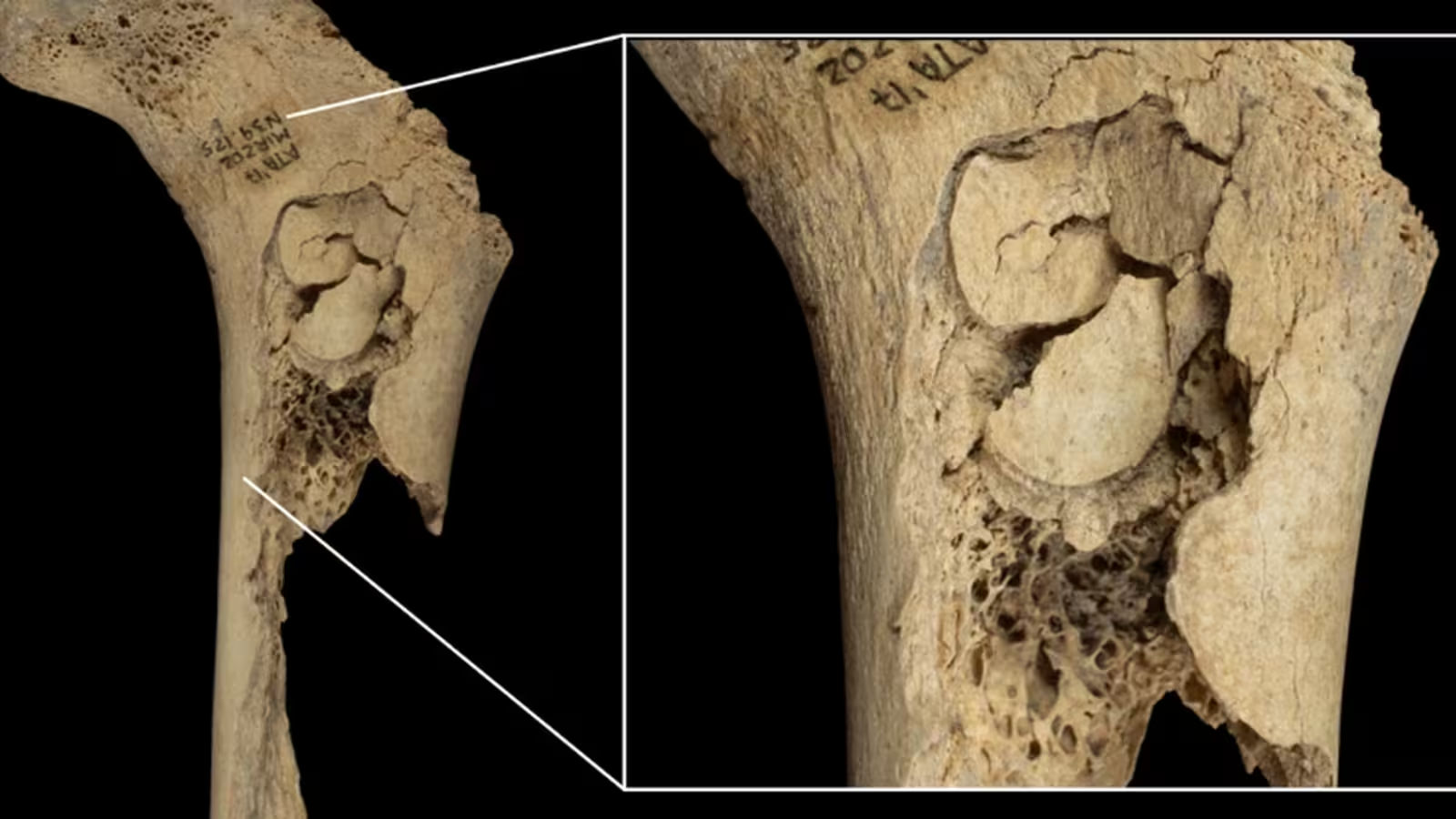

Researchers documented 650 human bone fragments showing deliberate postmortem processing. Specific indicators included so-called "pot-polishing"—rounded and smoothed bone extremities typical of prolonged contact with boiling liquids—discoloration and calcination from heating, and 132 bones bearing cut marks attributable to defleshing, skinning, disarticulation, evisceration and dismemberment. Some elements displayed peeling, a form of cortical alteration that can result from perimortem force or tooth removal; in several cases the patterning is consistent with gnawing by human teeth.

Key discoveries and interpretations

Two lines of chronological and geochemical evidence were critical. First, multiple radiocarbon determinations cluster tightly, indicating the victims were killed and processed within a limited interval that may have spanned a few days. Second, strontium isotope values show the individuals were local to the Atapuerca region, arguing against a long-distance funerary rite involving outsiders.

Taken together, the taphonomic signature and dating argue against interpretations such as nutritional cannibalism during famine or a routine ritual practice like transumption (the ingestion of relatives as part of funerary rites). "This was neither a funerary tradition nor a response to extreme famine," says Francesc Marginedas, evolutionary anthropologist and quaternary archaeologist at IPHES. Instead, the team interprets the evidence as pointing to a single episode of interpersonal or inter-group violence that culminated in the processing and consumption of defeated people, perhaps as an extreme form of social elimination or display of dominance.

Why this matters for Neolithic Iberia

The Atapuerca sequence is already pivotal for understanding European prehistory; the El Mirador assemblage adds nuance to a growing dataset that documents episodes of inter-group violence during the Neolithic on the Iberian Peninsula. Increased competition for fertile land, water, and resources as populations rose and migrated into new territories is a plausible background for episodic conflict. The presence of processed human remains alongside domestic refuse and animal bones suggests cannibalism in this instance functioned as part of a broader toolkit of violence rather than as an isolated cultural tradition.

Scientific background and broader implications

Cannibalism in prehistoric contexts can reflect diverse motivations: survival during famine, funerary rituals such as transumption, symbolic practices, or violent elimination of rivals. Interpreting which motive applies requires combining taphonomy, chronology, isotopic provenancing, and contextual archaeology. At El Mirador the combination of local origin, rapid timing, and butchery patterns favors an interpretation linked to conflict and social control.

Palmira Saladié of the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES) stresses the interpretive challenges: "Cannibalism is one of the most complex behaviors to interpret, due to the inherent difficulty of understanding the act of humans consuming other humans. Moreover, in many cases we lack all the necessary evidence to associate it with a specific behavioral context. Finally, societal biases tend to interpret it invariably as an act of barbarism." The El Mirador case, however, provides a rare combination of data that reduces interpretive ambiguity.

Related techniques and future prospects

Future work at El Mirador and comparable sites will benefit from high-resolution methods: micro-CT imaging to differentiate cut-mark microstriae, residue analysis to detect cooking media, ancient DNA to assess kinship between victims and local groups, and spatial GIS analyses to reconstruct depositional patterns. Advances in isotopic baselines and Bayesian modeling of radiocarbon dates will sharpen the temporal resolution of these events and improve our ability to distinguish episodic violence from recurrent practices.

Conclusion

The bone assemblage from El Mirador cave provides strong, multi-proxy evidence for a single late Neolithic event in which at least 11 local individuals were butchered and consumed. Radiocarbon dating, strontium isotope data and detailed taphonomic markers point away from famine or funerary ritual and toward an episode of violent social conflict—possibly a deliberate strategy of elimination or social deterrence between neighboring farming groups. While some questions remain, El Mirador is a key site for understanding the complex and context-dependent ways prehistoric communities treated human bodies, and it underscores how bioarchaeological methods can reveal episodes of interpersonal violence embedded in the archaeological record.

Source: nature

Comments