3 Minutes

Ozone Recovery and Climate: New Model Results

A recent modeling study finds that healing of the stratospheric ozone layer will contribute more to global warming this century than previously estimated. Researchers, led by Professor Bill Collins at the University of Reading, used atmospheric computer simulations to project changes through mid-century under a scenario with limited new air pollution controls but continued phase-out of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) in line with the Montreal Protocol of 1987. The models show that, although banning CFCs and HCFCs protects the ozone layer, the recovering ozone will increase radiative forcing and partially offset the climate benefits of removing those gases.

What the models simulated

The scenario assumed low adoption of additional clean-air policies while CFCs and HCFCs were removed as required by international treaty. Over the period 2015 to 2050, the simulations attribute roughly 0.27 watts per square meter (W m-2) of additional positive radiative forcing to changes in ozone. By comparison, carbon dioxide is projected to contribute about 1.75 W m-2 over the same interval, making ozone the second-largest simulated driver of additional warming by 2050 in this scenario.

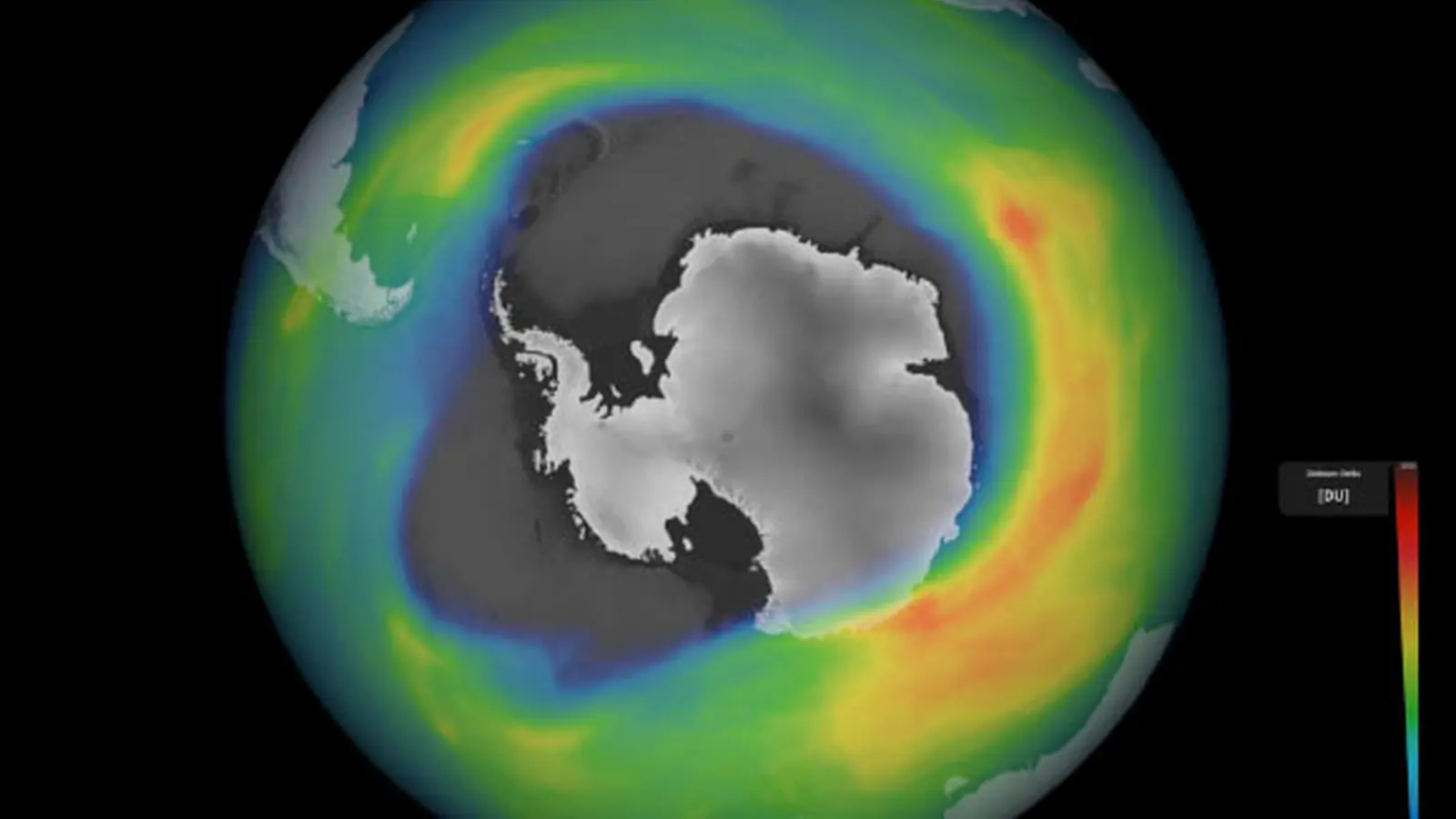

The researchers emphasise two distinct roles for ozone: stratospheric ozone, which shields the planet from harmful ultraviolet radiation, and tropospheric or ground-level ozone, which forms from air pollution and damages human health and ecosystems. While reductions in surface pollution will curb some ground-level ozone formation, the stratospheric ozone layer will continue to repair itself for decades regardless of local air-quality actions, producing an unavoidable component of warming.

Implications for climate policy and public health

These findings do not undermine the importance of preserving the ozone layer; protecting stratospheric ozone remains essential for preventing skin cancer and shielding ecosystems from intense ultraviolet radiation. However, the study suggests climate mitigation plans should explicitly account for ozone recovery when calculating future warming, greenhouse gas budgets, and adaptation needs. Policymakers may need to reassess expected benefits from removing certain ozone-depleting substances and integrate the dual roles of ozone into climate and air-quality strategies.

Conclusion

The study underscores a complex interaction between historical emissions controls, ongoing ozone recovery, and future climate forcing. CFC and HCFC bans remain vital for human and environmental health, but their unintended climate consequence — additional warming as the ozone layer heals — should be incorporated into updated climate projections and policy frameworks to ensure accurate risk assessment and effective mitigation planning.

Source: sci

Leave a Comment