6 Minutes

In July 2024 a powerful earthquake centered beneath Calama, northern Chile, challenged long-standing ideas about how deep earthquakes behave. New research led by scientists at the University of Texas at Austin reveals a hidden sequence of processes inside the subducting plate that dramatically amplified shaking at the surface. These findings change the way seismologists think about intermediate-depth events and could shift hazard assessments in subduction zones worldwide.

Scientists investigating the unusual 2024 Calama earthquake uncovered a hidden process deep within the subducting slab that allowed the rupture to intensify far more than expected for its depth. Their findings point to little-known thermal and mechanical forces that may reshape how researchers evaluate future seismic hazards in subduction zones.

A rupture that broke the rules

Most of the most destructive earthquakes—like the 1960 9.5-magnitude megathrust off central Chile—originate near the top of subduction megathrusts at relatively shallow depths. But the Calama event began roughly 125 kilometers below the surface inside the descending tectonic plate. Intermediate-depth earthquakes at these depths typically generate weaker surface shaking than shallow ruptures. The Calama quake, magnitude 7.4, did not fit that pattern.

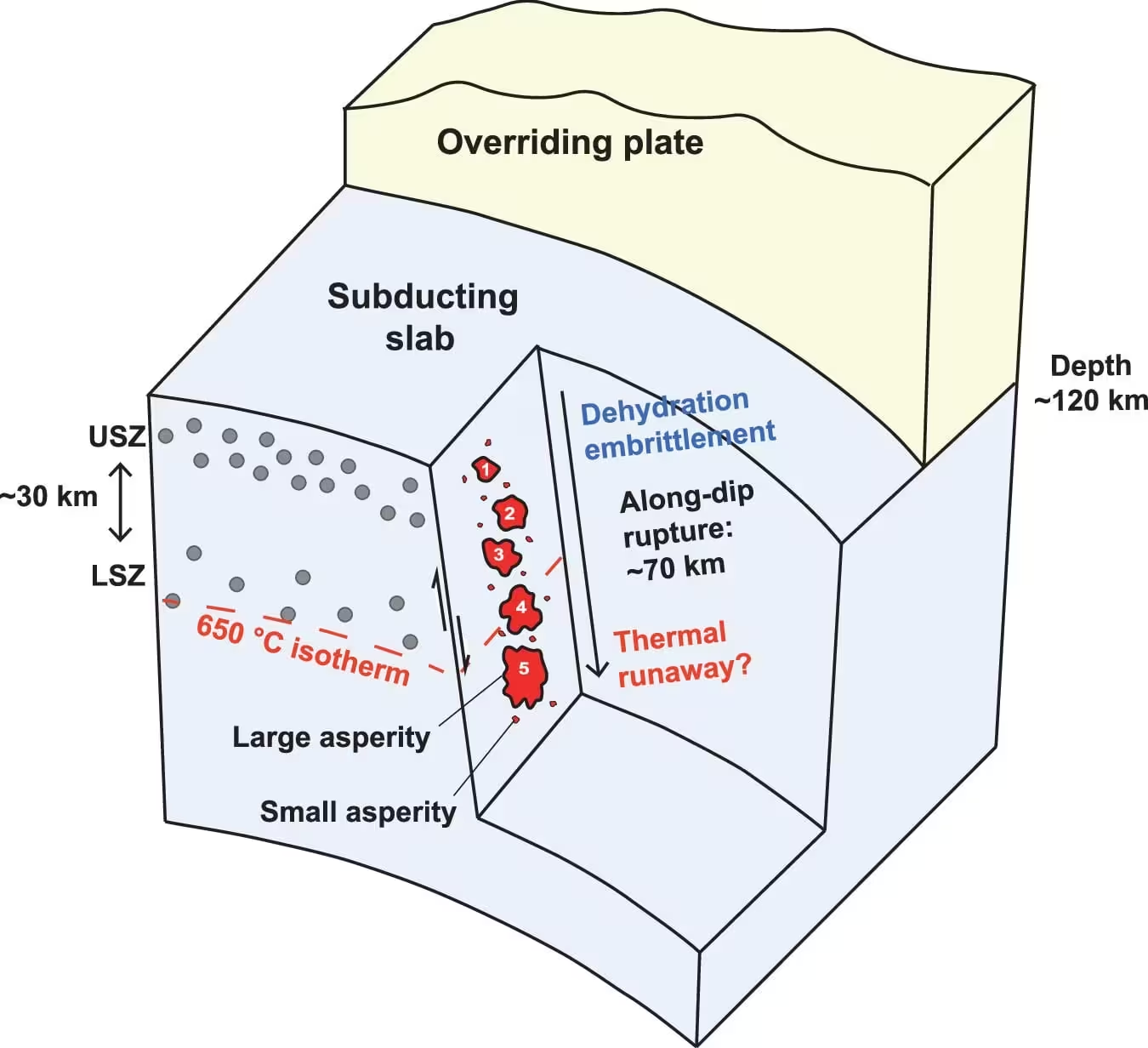

Lead author Zhe Jia and colleagues analyzed seismic waveforms, GPS-derived ground motion, and computational models to reconstruct the rupture in unprecedented detail. Instead of a single, simple failure driven by one process, the rupture sequence in Calama appears to have switched mechanisms mid-rupture—moving from classical dehydration embrittlement into a regime dominated by intense frictional heating called thermal runaway.

Two mechanisms, one powerful quake

Dehydration embrittlement is a widely accepted explanation for many intermediate-depth earthquakes. As a slab sinks deeper, pressure and temperature force mineral-bound water out of hydrous minerals. The expelled water increases pore pressure and weakens rock, promoting brittle failure even at relatively high pressures. This process typically ceases where temperatures climb above ~650°C.

What made Calama unusual is that the rupture did not stop at the expected thermal limit. Instead it propagated another ~50 kilometers into hotter zones where dehydration embrittlement should no longer operate. According to the UT Austin team, the initial rupture generated intense frictional heating at its tip. That locally elevated temperature and reduced rock strength, triggering a thermal runaway: a positive feedback in which slip produces heat, heat weakens the rock, and the weakening allows faster slip and more heat.

A figure from the study illustrating the two rupture mechanisms described in the paper, dehydration embrittlement and thermal runaway, and how they may have increased the force of the Calama earthquake. Credit: Jia et al.

How scientists pieced the story together

Reconstructing a deep rupture requires multiple datasets. The research team combined high-resolution seismic records from Chilean and international networks to track rupture propagation speed and direction. They used Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) data to measure fault slip and crustal deformation from the event. Finally, coupled physics-based simulations allowed the team to estimate temperature, mineralogy, and frictional heating along the fault plane at depth.

A team from The University of Texas at Austin and the University of Chile servicing a UTIG seismometer near Calama, Northern Chile, in 2024. UT graduate student Sabrina Reichert is in the background. U of Chile, Santiago researcher Bertrand J. M. Potin is in the foreground. Credit: Thorsten Becker/UT Austin

That integrated approach showed a rupture that accelerated and travelled unusually fast when it crossed into a hotter portion of the slab—consistent with a transition from dehydration-driven failure to thermally driven weakening. The result was far stronger shaking at the surface than expected from an earthquake at that depth.

Why the finding matters for seismic hazard

The implication is clear: intermediate-depth earthquakes are not always low-impact. When a rupture can tap into thermal runaway, its potential to produce severe ground shaking increases. For Chile—one of the most seismically active countries on Earth—this means hazard models and emergency planning must consider not just where quakes start, but how rupture processes can evolve at depth.

"These Chilean events are causing more shaking than is normally expected from intermediate-depth earthquakes, and can be quite destructive," Jia said in the publication. He and co-author Thorsten Becker emphasized the practical value of the work: improved rupture models can inform infrastructure resilience, early warning calibration, and rapid response priorities.

Expert Insight

"The Calama case highlights how dynamic the deep Earth can be," says Dr. Elena Márquez, a seismologist at the Southern Andes Geoscience Institute. "We often treat depth as a proxy for hazard, but mechanism matters. If a rupture can self-heat and transition into thermal runaway, its effective hazard footprint changes. This research gives us testable signatures to look for in other subduction zones."

Broader implications and next steps

The new study raises questions that researchers will pursue next. How common are mechanism transitions like the one inferred in Calama? Which slab compositions, thermal profiles, or stress states make thermal runaway more likely? Answering these questions will require denser seismic and GNSS monitoring, laboratory measurements of rock friction at high pressure-temperature conditions, and improved thermo-mechanical rupture simulations.

For policymakers and engineers, the take-away is that seismic hazard assessments should incorporate a richer range of rupture physics. In practical terms, that means revisiting building codes and emergency plans where intermediate-depth earthquakes are possible, and expanding monitoring in regions where subducting slabs carry hydrous minerals and steep thermal gradients.

Imagine a future seismic map that not only marks where earthquakes start, but also where a rupture might evolve into a more dangerous state. The Calama earthquake is a reminder: deep Earth processes can surprise us, and the best defense is better science and preparedness.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

DaNix

Is this even true? The thermal runaway idea sounds dramatic, maybe models overfit the data, or missing alternative explanations. skeptical but intrigued.

labcore

Wow didnt see that coming. A deep quake that basically self-heated into something way worse? Chile gotta rethink hazards, if true…

Leave a Comment