6 Minutes

Why running’s high impact isn’t necessarily bad for knees

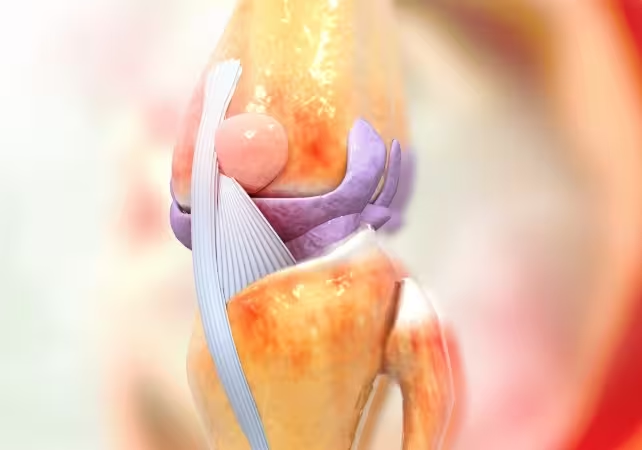

Running is often labeled as hard on the knees, but that simple portrait misses how the musculoskeletal system actually responds to load. Each foot strike while running generates forces roughly two to three times bodyweight. The knees do absorb more load during running than walking—commonly cited at around three times the load—but the presence of load alone is not synonymous with damage.

Human bone, cartilage, and connective tissue are living, adaptive tissues. Under regular, appropriate mechanical stress they remodel and strengthen. When mechanical load is removed—during prolonged bed rest, immobilization, or microgravity exposure—bone density and cartilage health decline. By the same logic, moderate, repeated impact from activities like running can stimulate positive adaptation in knee structures, provided the load is managed thoughtfully.

What the science says about running, cartilage and bone

Short-term loading from a run temporarily reduces cartilage thickness measured by imaging, but this compression is transient: thickness typically returns to baseline a few hours after exercise. Researchers interpret that cyclical compression and decompression as a healthy transport mechanism—mechanically driven fluid flow and nutrient exchange—helping maintain cartilage nutrition and resilience.

Longer-term observational studies suggest runners, on average, have thicker knee cartilage and higher bone mineral density than non-runners. Both factors are associated with reduced fragility and may lower risk factors for degenerative joint disease. Some epidemiological work has even proposed a dose–response trend: habitual runners show lower incidence of knee osteoarthritis than sedentary controls. However, causation is not fully established; confounding factors (body mass index, running history, and training load) complicate interpretation and more longitudinal randomized trials would strengthen the evidence base.

The positive effects on cartilage and bone also fit broader physiological principles: mechanical loading stimulates osteogenesis (bone formation) and promotes matrix turnover in articular cartilage—processes beneficial to joint longevity when exposure is progressive and balanced.

Starting or returning to running: practical guidance for safety and progression

If you’re thinking about beginning running—or restarting after a break—age alone is not an absolute barrier. A 2020 study of adults aged 65+ found that supervised plyometric (jump) training improved strength and function and was both safe and well-tolerated. Because plyometrics impose higher instantaneous joint loads than steady running, these findings support the idea that older beginners can adapt safely to impact exercise when progression is sensible.

General recommendations to reduce injury risk and support adaptation:

- Progress gradually: avoid sudden spikes in distance or frequency. A conservative weekly increase—adding only a small number of kilometres or minutes—helps tissues adapt.

- Use run–walk intervals to build tolerance: brief walking breaks interspersed with jogging reduce peak fatigue and distribute load during early training phases.

- Prioritize strength training: stronger hip, thigh and calf muscles improve shock absorption and alignment, lowering knee stress.

- Fuel recovery: adequate calories, carbohydrate and protein assist tissue repair. Low energy availability elevates risk for stress injuries.

- Support bone health: sufficient dietary calcium and vitamin D are linked to lower risk of stress fractures and better bone mineral density.

- Surface choice matters: softer surfaces (grass, well-maintained trails) reduce peak impact compared with concrete; alternating surfaces can moderate cumulative loading.

These measures address the most common running injuries—overuse syndromes caused by poor load management rather than inherent harm from running itself.

You're never too old to take up running. (MixMedia/Getty Images Signature/Canva)

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Marquez, a sports medicine researcher and physiotherapist, explains: “Joints are dynamic organs. Repetitive, progressive loading—applied prudently—stimulates adaptation in cartilage and bone. The real problem is abrupt overload: rapid mileage jumps, insufficient recovery, or compounding risk factors like low bone density or inadequate nutrition. With staged progression, strength work and sensible fueling, many people, including older adults, can gain musculoskeletal benefits from running.”

This practical perspective reflects current multidisciplinary evidence from biomechanics, imaging studies and clinical trials: running can be an effective stimulus for joint health when combined with gradual progression, conditioning and proper recovery.

Implications and future directions

The emerging consensus reframes running from a presumed cause of knee degeneration to a potential protective activity for many people—when practiced intelligently. Future research priorities include randomized controlled trials that track cartilage and bone changes in new runners across age groups, dose–response studies to define optimal training volumes, and investigations into individual risk modifiers such as prior injury, body composition and genetics.

Technology and monitoring tools—wearable impact sensors, smartphone gait analysis and accessible bone-health screening—may also help personalize training plans and reduce injury risk. Translating current findings into public health guidance means balancing enthusiasm for running’s cardiovascular and musculoskeletal benefits with clear messaging about gradual progression, strength training and nutrition.

Conclusion

Running is a high-impact activity, but impact is not inherently harmful. Scientific evidence indicates that controlled, progressive running can stimulate cartilage nutrition and bone density, potentially supporting knee health and longevity. Most running injuries are due to overuse and rapid increases in load, not running itself. Start slowly, prioritize strength and recovery, fuel adequately, and choose softer surfaces while building tolerance. Under these conditions, running’s benefits for joints—and for cardiovascular and metabolic health—appear to outweigh the risks for many people.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment