6 Minutes

Discovery and archaeological context

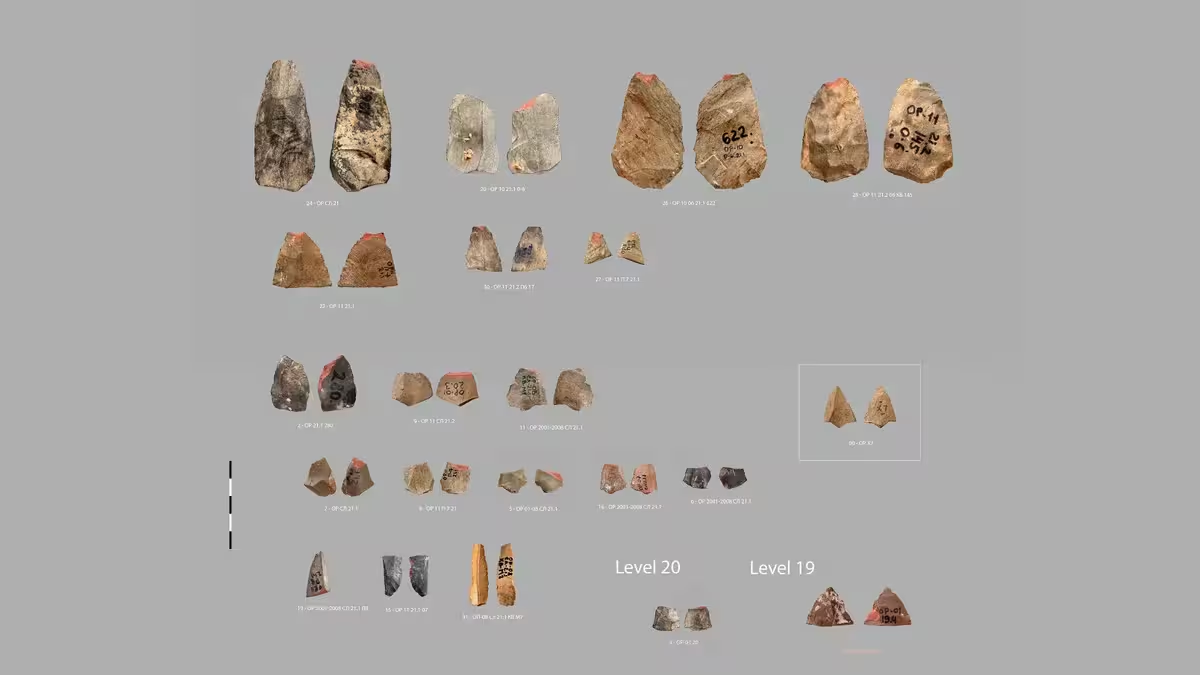

Researchers working at Obi-Rakhmat, a Paleolithic site in northeastern Uzbekistan, have reexamined thousands of stone artifacts and identified a set of tiny, triangular stone points that may represent the world's oldest arrowheads. The finds — described in a study published Aug. 11 in PLOS One — consist of small, narrow microliths or "micropoints" that had previously been overlooked or dismissed because many were fractured. Careful analysis now suggests these pieces are too slender to have functioned as spear tips or cutting tools and instead are compatible in form and damage patterns with hafted arrow tips mounted on lightweight shafts.

Obi-Rakhmat has long yielded diverse stone tool types including broad blades and smaller bladelets. During renewed study, archaeologists documented numerous diminutive points whose dimensions, edge wear and fracture morphology align with the functional expectations for projectile tips. The assemblage is radiometrically dated to roughly 80,000 years ago, making these micropoints approximately 6,000 years older than previously proposed early arrow evidence from Ethiopia at ~74,000 years. If confirmed as arrowheads, the Obi-Rakhmat micropoints would extend the known antiquity and geographic distribution of bow-and-arrow technology deep into Central Asia.

Analyses, methods and dating

The argument that these microliths functioned as arrow tips rests on three main lines of evidence: their narrow cross-sections and triangular profiles, diagnostic impact fractures and micro-wear consistent with high-velocity impact, and the absence of alternative hafting geometries that would accommodate such small points. The authors applied standard lithic-analysis protocols: metric comparison with known projectile point typologies, microscopic edge-wear assessment, and fracture-pattern classification used to infer ballistic events. Contextual dating derives from stratigraphic associations and previously published chronologies for Obi-Rakhmat, placing the micropoint-bearing horizons near ~80,000 years before present.

The preservation environment at the site has not retained perishable components such as wooden shafts or bow constructions, so interpretation relies primarily on the morphology and damage signatures recorded on the stone implements. Study co-author Hugues Plisson, an associate scientist at the University of Bordeaux, emphasized that the narrow form factor of the micropoints strongly constrains plausible functions; in his view they are most consistent with being hafted on arrow-like shafts and used in hunting.

Implications for Paleolithic technology and subsistence

If the micropoints from Obi-Rakhmat are confirmed as arrowheads, this discovery changes our understanding of the spatial and temporal spread of advanced hunting technologies such as bows and arrows. Christian Tryon, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the University of Connecticut who was not part of the study, noted that the evidence suggests "complicated early weapons and hunting technologies were more geographically widespread at an earlier date than previously supposed." The presence of microlith technology at this time could have aided human groups in exploiting a wider range of prey and habitats, offering improved hunting efficiency and competitive advantages in landscapes shared with other hominin populations.

Who made these tools?

At present, the makers of the Obi-Rakhmat micropoints are not conclusively identified. Human remains recovered at the site include teeth and skull fragments from a juvenile dated to the same general period. The dental morphology was reported to resemble Neanderthal features, while cranial details were ambiguous, leaving open possibilities that the individual belonged to Homo sapiens, a Neanderthal, or an interbreeding hybrid involving Denisovans or Neanderthals. Central Asia, during the interval around 80,000 years ago, was a mosaic of hominin populations, and the region may have seen arrivals of anatomically modern humans dispersing from the Levant into Eurasia.

Study co-author Andrey Krivoshapkin, director at the Siberian branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences' Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, acknowledged likely skepticism: neither bows nor shafts preserve well archaeologically, so some colleagues may question the arrow interpretation. Nevertheless, the researchers suggest the microlith technology could plausibly have been introduced by migrating modern humans from the eastern Mediterranean and subsequently supported successful subsistence strategies in Central Asian settings already occupied by other hominins.

Broader scientific significance and future research

This discovery has several broader implications for archaeology and human evolution. First, it supports the notion that complex weapon systems — including small-stone projectile tips compatible with arrows — may have evolved earlier and in more regions than the traditional, Africa-centered narratives imply. Second, it raises new questions about cultural transmission, innovation, and intergroup competition in Pleistocene Eurasia. The Obi-Rakhmat team plans further excavations and interdisciplinary analyses, including attempts to recover genetic material and to seek archaeological linkages to Levantine populations. They also intend to reexamine nearby and potentially older sites in Central Asia in search of even earlier evidence for microlithic projectile technology.

Expert Insight

Dr. Laura Mendel, a fictional archaeologist specializing in prehistoric weapon systems, comments: "These micropoints from Obi-Rakhmat are a notable addition to the global record of projectile technology. The morphological and impact-wear data are convincing for a hunting function; however, without organic preservation of shafts or direct hafting traces, we must approach the arrow interpretation cautiously. If subsequent work confirms an arrow-based hunting strategy, it will force us to revisit models of how and when bow technology emerged and spread among Pleistocene hominins."

Her assessment highlights both the significance of the find and the need for further corroborating evidence such as residue analysis, microwear replication experiments, and targeted searches for hunting locales where arrows were likely used.

Conclusion

The small triangular micropoints recovered from Obi-Rakhmat, Uzbekistan, represent a potentially transformative discovery in Paleolithic archaeology: dated to about 80,000 years ago, they may be the oldest known arrowheads. While key organic components such as bows and shafts are absent and the identity of the toolmakers remains unresolved, lithic morphology and fracture patterns support a projectile interpretation. These findings expand the possible geographic and chronological range of advanced hunting technologies and underline how reassessment of previously excavated collections can yield major insights. Ongoing excavations, genetic studies, and comparative analyses will be necessary to confirm whether these microliths reflect an early and widespread adoption of bow-and-arrow technology in Pleistocene Eurasia.

Source: livescience

Leave a Comment