5 Minutes

Over the past century, many high-income countries experienced dramatic increases in average lifespan. A new international analysis, however, finds that those gains have already decelerated: while life expectancy will still rise in developed nations, the rate of improvement is about half of what it was during the early 20th century. This change makes it unlikely that recent birth cohorts will reach an average age of 100 without major medical breakthroughs.

Study scope and methods

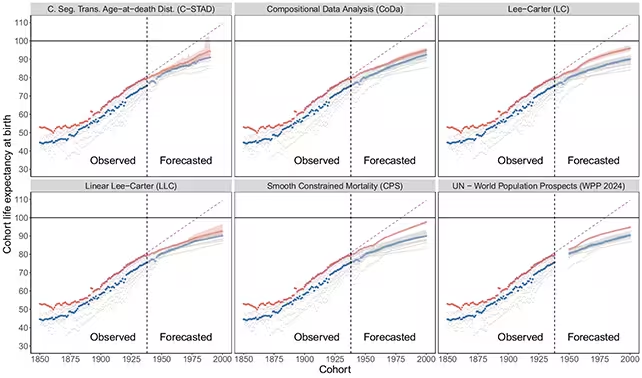

The research pooled historical population records for 23 high-income, low-mortality countries and applied six different forecasting models to project future longevity for cohorts born primarily between 1939 and 2000. By combining empirical demographic data with multiple statistical approaches, the team reduced model-specific bias and estimated generational improvements in life expectancy across the 20th century.

Key finding: cohorts born after the late 1930s show substantially smaller generational gains in average lifespan than earlier cohorts. The analysis reports an average increase of roughly 5.5 months per generation for people born from 1900 to 1938, compared with only 2.5–3.5 months per generation for those born between 1939 and 2000.

Why progress has slowed

Researchers attribute the slowdown largely to the diminishing returns of improvements in infant and early-childhood survival. Much of the 20th-century rise in life expectancy resulted from dramatic reductions in child mortality through vaccines, antibiotics, safer childbirth, and better sanitation. In many wealthy countries, those gains have largely been realized, leaving less room for continued rapid increases from the same causes.

At the same time, improvements in adult survival now face different biological and social constraints: chronic diseases, lifestyle factors, environmental exposures, and complex age-related conditions such as dementia present harder challenges than early-life infectious threats did a century ago. As Héctor Pifarré i Arolas (University of Wisconsin–Madison) noted, absent major breakthroughs that directly extend human lifespan, even large improvements in adult survival are unlikely to restore the early-20th-century pace of gains.

Implications for policy and planning

Slower increases in life expectancy have practical consequences. Governments, pension funds, and healthcare systems base long-term budgeting and infrastructure on demographic projections. Expecting continuous, fast gains in longevity could lead to underfunded pensions or inadequate eldercare capacity. At the individual level, clearer expectations about likely lifespan affect retirement planning, insurance, and personal health investments.

The study also highlights geographic and socioeconomic variation: global averages mask disparities, and life expectancy remains sensitive to public health policy, socioeconomic conditions, and access to medical care. Lifestyle factors—exercise, diet, smoking, pollution exposure and even proximity to coastlines—continue to influence individual outcomes and represent areas where policy and behavioral changes could still yield meaningful benefits.

Research gaps and future directions

The authors stress that their projections assume no unprecedented medical breakthrough. Advances such as effective anti-aging therapies, widespread gene therapies, or major innovations in chronic disease prevention could alter trajectories. The study therefore indicates where research and health-system investments could be most effective, particularly in addressing age-related diseases and widening access to proven preventive care.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Ruiz, a fictional population health scientist: "This study refocuses attention on where the easiest gains were made historically—safeguarding infants and young children. Now the frontier is older ages, which requires different tools: integrated chronic-care models, precision medicine, and social policies that reduce inequality. Slower population-level gains don't mean individual longevity can't improve; they mean the low-hanging fruit is gone and new strategies are needed."

Conclusion

The unprecedented surge in life expectancy during the first half of the 20th century—driven largely by reductions in child mortality—appears unlikely to be repeated soon in wealthy nations. While average lifespans should continue to rise modestly, the rate is expected to remain substantially lower than in past generations. This shift has direct implications for public policy, healthcare planning, and personal retirement strategies, and it highlights the importance of targeted research into age-related diseases and equitable access to medical advances.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment