5 Minutes

Recent research has strengthened an unsettling hypothesis: Alzheimer's disease may involve infectious processes that originate outside the brain, including the oral cavity. Multiple studies now point to Porphyromonas gingivalis—the bacterium most closely associated with chronic periodontitis (gum disease)—as a potential contributor to Alzheimer's pathology. This idea challenges the conventional view of Alzheimer's as purely an intrinsic neurodegenerative disorder and opens new avenues for diagnosis and treatment.

Scientific background and why P. gingivalis matters

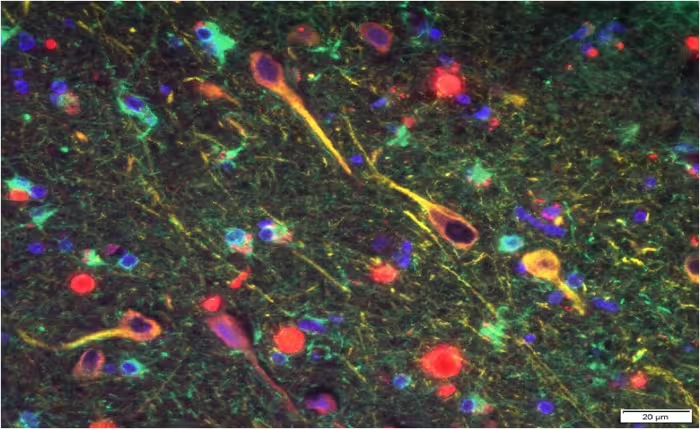

Porphyromonas gingivalis is a Gram-negative, anaerobic bacterium implicated in chronic periodontal inflammation. Long-term periodontal infection drives systemic inflammation and can release bacterial components and toxins into the bloodstream. In the context of Alzheimer's research, investigators have focused on two linked phenomena: the emergence of hallmark proteins in the brain—amyloid beta (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylated tau—and the presence of microbial antigens or enzymes that might trigger or exacerbate this pathology.

A key finding published in 2019 identified P. gingivalis DNA, bacterial proteins, and toxic proteases called gingipains in the brains of deceased people with Alzheimer’s disease. The study further detected gingipain antigens in brains of individuals who showed Alzheimer’s pathology but had not been diagnosed with dementia during life. That pattern suggests bacterial invasion might precede clinical cognitive decline rather than being a secondary consequence of poor oral hygiene in people with dementia.

Study details and main discoveries

In laboratory experiments coordinated by Cortexyme and led by researchers including Jan Potempa and Stephen Dominy, investigators combined human postmortem brain analyses with animal models. Core observations included:

- Detection of P. gingivalis genetic material and gingipain enzymes in Alzheimer’s brains, associated with tau and ubiquitin markers.

- In mice, oral infection with P. gingivalis produced brain colonization, increased Aβ production, and neuroinflammatory changes consistent with Alzheimer-like pathology.

- A small-molecule inhibitor developed by Cortexyme, COR388 (atuzaginstat), reduced bacterial load in mouse brains, lowered amyloid-beta production, and decreased neuroinflammation in preclinical models.

These results do not by themselves prove causation for human Alzheimer's, but they satisfy several biological plausibility criteria: a plausible route of infection (oral to systemic circulation to brain), identification of microbial components within diseased tissue, and modulation of both microbial presence and disease-associated markers when the bacterial proteases were targeted.

Markers and mechanisms

Gingipains are proteolytic enzymes secreted by P. gingivalis that can degrade host proteins and modulate immune responses. Their presence correlated with higher levels of tau pathology and ubiquitin tagging—hallmarks of disrupted protein homeostasis in neurons. Amyloid beta, long associated with plaque formation in Alzheimer’s, was also increased in infected mice, supporting the hypothesis that Aβ may be produced as part of an innate immune response to microbial invasion.

Implications for treatment and prevention

If oral pathogens contribute to Alzheimer's progression, strategies to reduce periodontal disease and to target bacterial virulence factors could become part of a multi-pronged approach to prevention and early intervention. Therapeutics aimed at neutralizing gingipains or clearing chronic oral infections may complement existing research into amyloid-targeting drugs and anti-inflammatory strategies.

"Infectious agents have been implicated in the development and progression of Alzheimer's disease before, but the evidence of causation hasn't been convincing," Stephen Dominy and collaborators noted. "Now, for the first time, we have solid evidence connecting the intracellular, Gram-negative pathogen, P. gingivalis, and Alzheimer's pathogenesis." David Reynolds from Alzheimer's Research added that, while benefits so far have been limited to animal studies, exploring many approaches is essential given the long drought of new dementia treatments.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Morales, neurologist and microbiome researcher, comments: “This body of work highlights the interconnectedness of systemic health and brain health. Oral pathogens like P. gingivalis can create a chronic inflammatory state that, over decades, might push a susceptible brain toward neurodegeneration. It does not single-handedly explain all cases of Alzheimer's, but it suggests practical prevention steps—improved periodontal care and targeted antimicrobial strategies—that could reduce risk. Crucially, large-scale clinical trials are needed to determine whether interventions that reduce oral infection alter dementia trajectories in humans.”

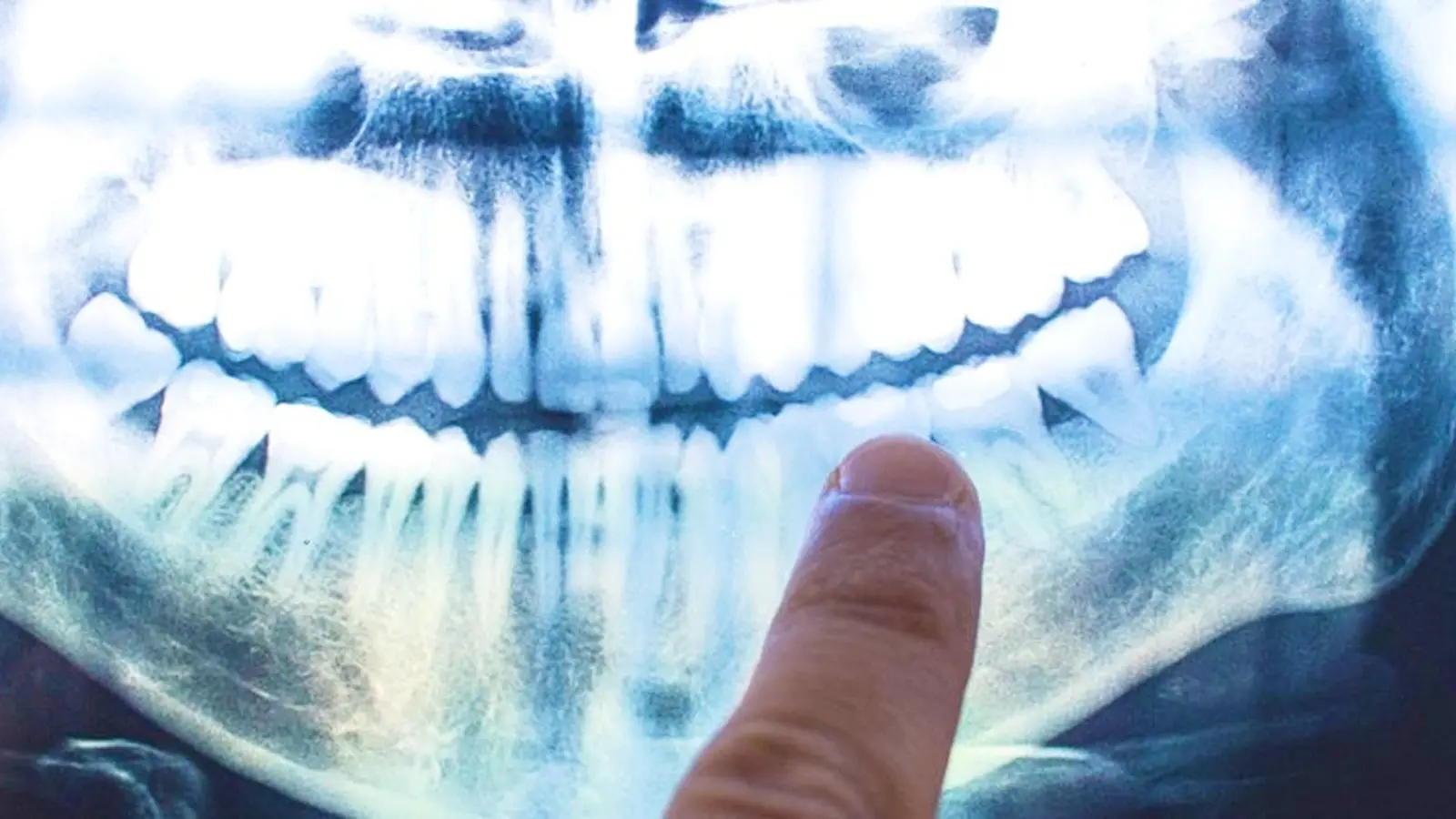

Does gum disease cause Alzheimer's, or could those with dementia be at greater risk of poor dental hygiene? (Jonathan Borba/Unsplash)

Conclusion

Evidence linking oral pathogens—especially Porphyromonas gingivalis—and Alzheimer’s-related brain changes has shifted the field toward considering infection and chronic inflammation as contributors to neurodegeneration. While causation in humans remains unproven, the detection of gingipains and bacterial signatures in Alzheimer’s brains, together with supportive animal data and early-stage therapeutic candidates like COR388, justify further clinical research. Meanwhile, good oral hygiene and periodontal care represent low-risk measures with potential long-term benefits for systemic and brain health.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment