5 Minutes

Ancient giants under microscopic threat

New research shows that some of South America's largest dinosaurs suffered from a destructive bone infection roughly 80 million years ago. Paleontologists examined six sauropod skeletons recovered from the Vaca Morta site in São Paulo state, Brazil, and found pathological lesions consistent with osteomyelitis — an inflammatory bone disease caused today by bacteria, fungi, viruses, or parasites.

Osteomyelitis is well known in modern vertebrates, affecting mammals, birds and reptiles worldwide. The new study, published in The Anatomical Record (2025), provides the clearest evidence yet that this illness also afflicted large dinosaurs during the Late Cretaceous and may have been an active cause of morbidity and mortality among sauropods that occupied wet, floodplain ecosystems.

Fossil evidence and site context

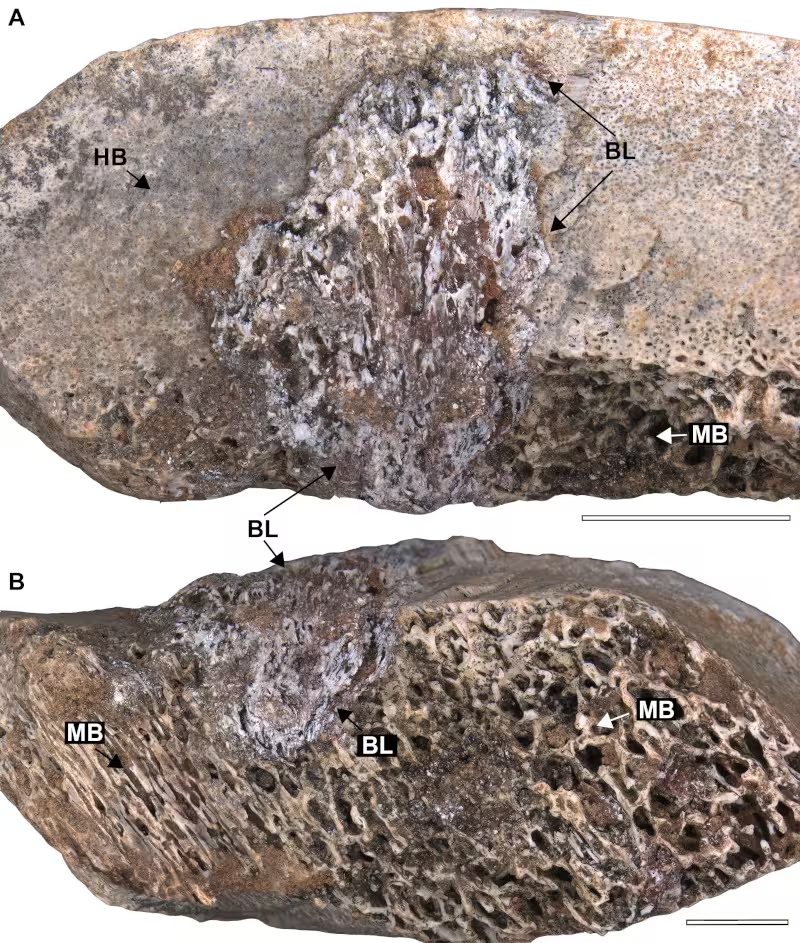

The fossils were collected between 2006 and 2023 at the "Vaca Morta" locality. Many of the affected bones show no signs of healing, indicating the infections were ongoing when the animals died and might have contributed to their deaths. Some specimens show internal-only lesions, while others display external, rounded protrusions and complex, chaotic bone architecture not attributable to bite marks or non-infectious trauma.

The palaeoenvironment reconstructed for this region consisted of shallow, slow-moving rivers and standing pools — habitats that can concentrate pathogens and the invertebrate or vertebrate carriers that spread them. Footprints and other sauropod remains from Brazil frequently come from floodplains and swampy sediments, suggesting these giants regularly used the very ecosystems that supported disease transmission.

"The bones we analyzed are very close to each other in time and from the same palaeontological site, which suggests that the region provided conditions for pathogens to infect many individuals during that period," notes lead author Tito Aureliano of the Regional University of Cariri (URCA), summarizing the spatial and temporal clustering of the finds.

Pathology, progression and implications

Microscopic and macroscopic analysis of the lesions led the research team to conclude the infection progressed rapidly in some animals. The lesions' irregular, 'chaotic' internal structure distinguishes them from healed wounds or simple fractures and is consistent with aggressive osteomyelitic processes seen in modern vertebrates.

Different bones and different sauropod individuals exhibit a spectrum of lesion morphologies, which may reflect variation in host immune response, infection route (e.g., direct wound contamination vs. blood-borne spread), or the identity of the pathogen. The study does not identify a specific microbial agent — ancient DNA or protein evidence is rarely preserved in such fossils — but the pattern is compatible with bacterial osteomyelitis, the most common form in extant animals.

These findings nuance our understanding of dinosaur life: while megafaunal size and widespread distributions are often emphasized, disease ecology could have been a significant, but underappreciated, force shaping dinosaur populations and behaviour.

Expert Insight

Dr. Isabel Moreno, a fictional paleopathologist with two decades of experience studying vertebrate bone disease, comments: "This research is important because it links palaeoenvironmental reconstructions with direct pathological evidence. When large herbivores repeatedly visit wetland habitats, they increase exposure to vector-borne and waterborne pathogens. For sauropods, chronic or acute osteomyelitis could have reduced mobility, made them vulnerable to predators, and impacted reproductive success — factors that matter in population dynamics over geological timescales."

The team’s multidisciplinary approach — integrating field stratigraphy, comparative pathology, and modern infection models — demonstrates how paleontology and disease ecology can intersect to reveal previously hidden pressures on ancient ecosystems.

Conclusion

A cluster of sauropod fossils from Brazil provides compelling evidence that osteomyelitis affected large dinosaurs about 80 million years ago. The pattern of lesions, their lack of healing, and the floodplain setting of the Vaca Morta site together suggest that aquatic and wetland habitats facilitated pathogen transmission. While the specific causative organisms remain unidentified, the study highlights disease as an important ecological factor in dinosaur communities and underscores the value of paleopathological research for reconstructing ancient life and environments.

The 80-million-year-old fossilized bone of a sauropod showing lesions caused by osteomyelitis (BL arrow). (Aureliano et al., The Anatomical Record, 2025)

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment