8 Minutes

Summary and study highlights

A large Danish observational study tracking more than 85,000 adults reports that people with very low body mass index (BMI) face substantially higher mortality than those in the mid-to-upper end of the conventionally "healthy" BMI range. The research, presented at the Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and not yet peer reviewed, identified a U-shaped relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality: the greatest excess risk occurred at the lowest BMIs, while mortality rose again only at very high BMIs.

Specifically, participants with BMI below 18.5 had nearly three times the risk of premature death compared with a reference group at BMI 22.5–24.9. Individuals in the lower end of the traditionally "healthy" range (18.5–19.9) had roughly double the risk, and even those with BMI 20.0–22.4 showed an elevated risk (about 27% higher) compared with the reference group. By contrast, people in BMI bands generally classified as overweight or mildly obese (25–35) did not show a statistically significant increase in mortality in this cohort; only those with BMI ≥40 experienced a markedly higher risk (about 2.1 times).

These patterns complicate common assumptions that lower BMI is uniformly protective and raise questions about how BMI thresholds should be interpreted in contemporary clinical practice and public health messaging.

Scientific context and what BMI measures

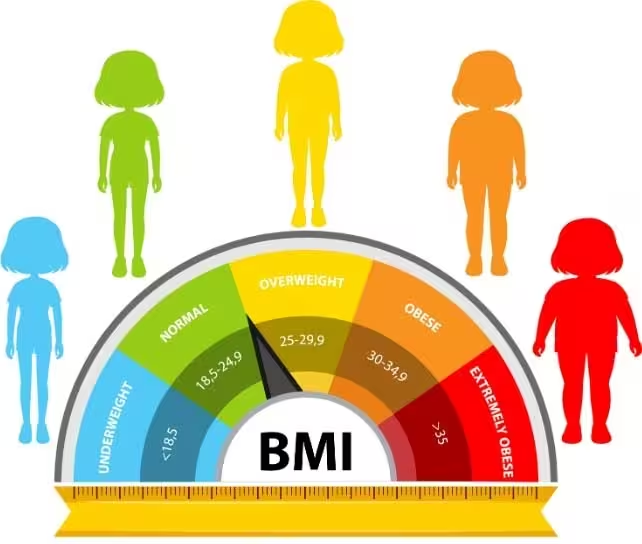

Body mass index is a simple ratio of weight (kg) to height squared (m2) designed as a population-level screening tool for body size categories: underweight, healthy weight, overweight and obesity. BMI is widely used because it is inexpensive and easy to calculate, but it is a blunt proxy that does not distinguish fat mass from lean mass, nor does it capture fat distribution (visceral vs subcutaneous), diet quality, fitness, or other metabolic health markers.

Historically, BMI cutoffs were developed using datasets dominated by white European men. As a result, standard categories can misclassify risk across racial and ethnic groups. Several countries and health services now adjust BMI thresholds for specific populations where evidence supports different risk patterns for diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other outcomes.

Mechanisms: why very low BMI may increase risk

Physiological reserves and illness resilience

Low body mass can reflect limited energy and nutrient reserves. During acute illness, trauma or prolonged stress, the body draws on fat and muscle stores to meet metabolic demands. People with very little adipose and lean mass may have reduced resilience: they can deplete reserves faster, impairing recovery, immune response and ability to tolerate treatments.

Unintentional weight loss as a disease marker

Unintentional weight loss commonly precedes diagnoses of conditions such as cancer, chronic infection, and metabolic disorders including type 1 diabetes. In cohort analyses, low BMI can therefore be both a causal vulnerability and a signal of pre-existing disease that increases short-term mortality risk. The Danish authors acknowledge that some participants likely underwent imaging and body scans for suspected medical problems—introducing potential reverse causation bias.

Key discoveries and implications for clinicians and public health

The primary finding — a U-shaped mortality curve with the highest risk at very low and very high BMIs — reinforces two important points: first, being underweight is not benign, particularly in older adults; second, modestly higher BMI does not always translate to higher mortality in modern, medically managed populations. Advances in treatment of obesity-related conditions (for example, improved blood pressure control, statins, and diabetes therapies) may shift the BMI range associated with lowest mortality.

The authors suggest that, at least in this Danish cohort, the BMI band of 22.5–30.0 may now correspond to the lowest mortality risk. That observation is specific to the studied population and should not be extrapolated uncritically to other demographic groups or used as sole guidance for individual care.

Limitations and methodological considerations

This study is observational and preliminary, with several limitations to consider:

- Confounding and reverse causation: low BMI can reflect underlying disease that drives mortality, rather than BMI being the independent cause of death. The cohort included participants who had clinical scans for suspected health issues, which may bias results.

- Single measure vs longitudinal change: a single BMI measurement does not capture weight history or recent unintentional weight loss, both of which carry different prognostic implications.

- Generalizability: the sample is Danish; genetic, environmental, and healthcare-system differences mean findings may not apply universally.

- BMI as an imperfect metric: reliance on BMI alone omits muscle mass, fat distribution, fitness, diet quality, and socioeconomic factors that strongly influence health outcomes.

Given these constraints, the data are informative for hypothesis generation and reinforce the need to incorporate richer clinical measures (blood biomarkers, imaging, functional status, diet and activity assessment) when making individualized health decisions.

Policy relevance and clinical practice

The study adds to an evidence base prompting re-evaluation of rigid BMI cutoffs for clinical decision-making. Many healthcare systems currently use BMI thresholds to determine access to treatments (for example, eligibility for some surgeries or fertility services). If BMI thresholds do not accurately reflect risk across diverse populations, they can produce inequitable outcomes. The authors and commentators recommend combining BMI with additional assessments when possible, and caution against using BMI in isolation to make high-stakes decisions.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Martin, science communicator and epidemiologist, comments: "This Danish analysis highlights a recurring theme in population health: simple metrics are valuable but inherently limited. BMI is an efficient screen but not a definitive measure of health. Clinically, we need to interpret a low BMI as a potential red flag for frailty or underlying disease, particularly in older adults, and pair it with functional assessments and laboratory tests. For public messaging, it's important to avoid binary framing—thin is not always healthy, and higher weight is not always harmful. Context matters."

Future research directions

To clarify causality and clinical implications, future studies should:

- Use longitudinal designs tracking weight trajectories and intentionality of weight change.

- Combine BMI with measures of body composition (DEXA, bioimpedance), fat distribution (waist circumference, imaging), and metabolic markers.

- Explore heterogeneity by age, sex, ethnicity and comorbidity status to establish population-specific risk profiles.

- Investigate mechanisms linking low BMI to mortality, including sarcopenia, immune dysfunction and treatment tolerability in chronic disease.

Such work can guide refined risk stratification and more equitable policy decisions about BMI-based thresholds in healthcare.

Conclusion

The Danish cohort study underscores that very low BMI is associated with substantially higher mortality, while modestly elevated BMI did not correspond to increased risk in this population except at extreme obesity. These results do not indict or vindicate BMI as a universal health metric; instead, they emphasize its limitations and the need for nuanced interpretation. Clinicians and public health practitioners should treat low BMI as a potential marker of vulnerability, evaluate the broader clinical context, and work toward integrated assessments that combine anthropometry with metabolic, functional and social-health measures. Further research is required to determine how best to adapt BMI cutoffs and clinical guidelines across diverse populations and healthcare settings.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment