12 Minutes

At the Foreign Investors Annual Summit 2025 in Vilnius—hosted by the American Chamber of Commerce in Lithuania (AmCham Lithuania) and staged in the main ballroom of the Radisson Blu Hotel—a five-speaker panel tackled one of the thorniest questions for any competitive economy: how to turn education, health, and talent into durable growth. Moderated by Nicholette Ross (Site Selection Consultant, Global Location Strategies), the session gathered perspectives from central banking, pharmaceuticals, international education, digital engineering, and location strategy. What followed was an unusually frank, highly practical conversation about skills, procurement of people, health as productivity, and the policy plumbing that either accelerates or slows everything down.

A global problem that is felt locally

Moderator Nicholette Ross set the terms right away: talent is the No. 1 filter in site selection, but the conversation can’t stop at “how many engineers exist right now.” Investors ask about pipelines, conversion, stickiness—and, increasingly, health and quality-of-life infrastructure that keeps people productive and willing to stay.

Elias van Herwaarden—who has helped more than 800 corporate projects choose locations for manufacturing, R&D, IT, and headquarters—added a dose of scouting realism. For shared services and tech, talent volume and growth are decisive. For manufacturing, the first two questions are often painfully simple: Do you already have a prepared industrial site? and How many people in the surrounding labor shed can we actually hire? “Spreadsheets matter,” he said, “but speed to start and labor depth decide outcomes.”

His sharper challenge landed later: Where are the young people in this conversation? In rooms where policymakers and executives design talent systems for the future, he argued, youth voices are under-represented. “Everywhere in the world people say ‘we don’t have enough talent.’ It’s a global diagnosis. But if you want to fix it, bring the next generation to the table. Companies that listen to the young are the ones that hire them.”

Education’s job: portability, belonging, and versatility

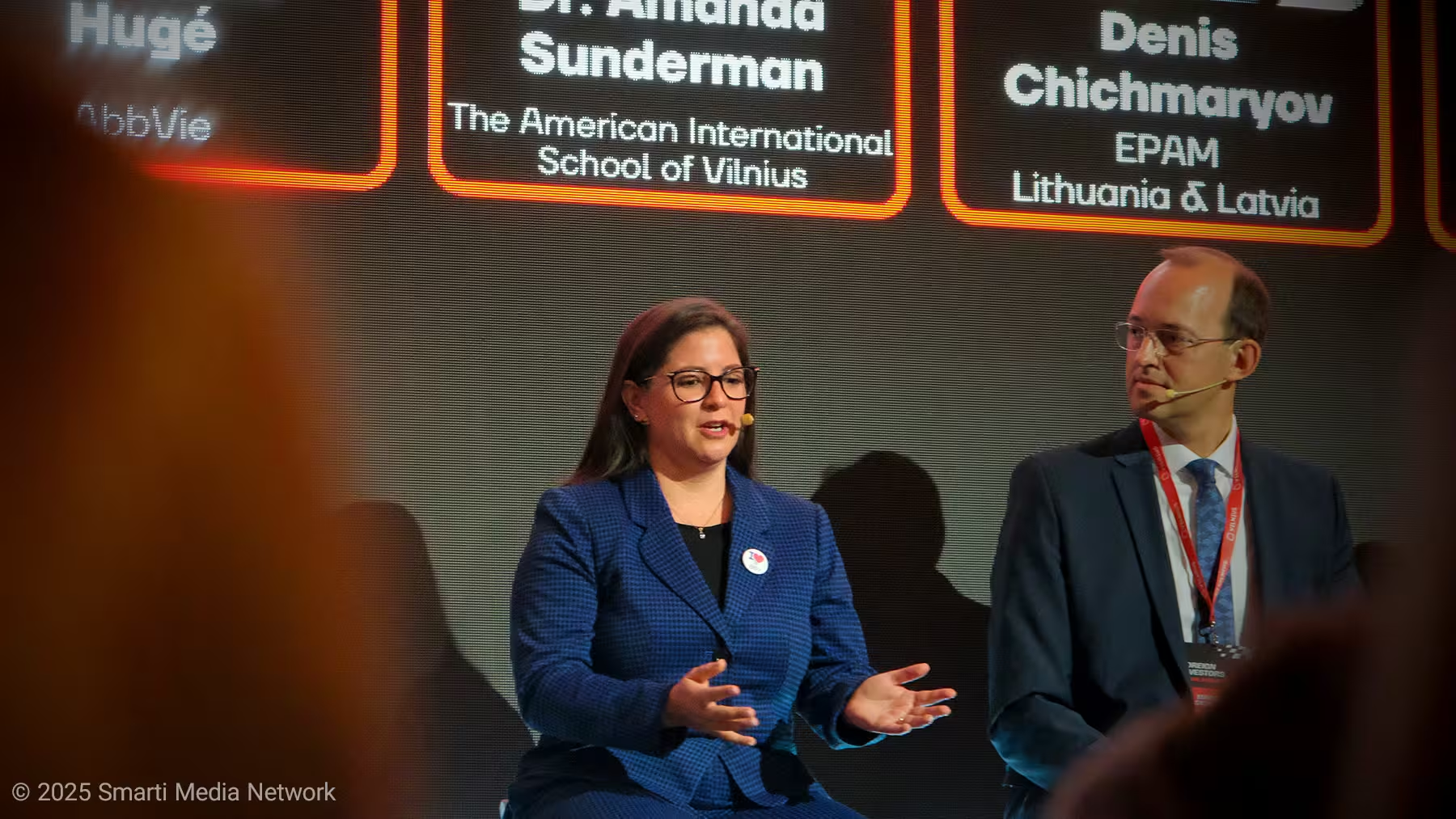

From the vantage point of international education, Dr. Amanda Sunderman explained why portability matters to global families who relocate for work. “A parent thinking about a new assignment is actually thinking about the three-year-old and the eighteen-year-old,” she said. International schools provide transferable curricula, delivered in English, that allow children to slot into new systems without losing momentum. At her school in Vilnius, every student also studies Lithuanian, and day-to-day learning unfolds among 20–30 nationalities. That multicultural fluency is an economic skill in its own right.

Sunderman’s second point connected education to workforce retention: belonging. “Social connections predict how long employees stay with companies,” she said. “We cultivate well-being and community for the whole family. That soft stuff shows up later as lower churn and higher engagement.”

She then described how schools are redesigning learning for volatility: “We are developing versatile learners—comfortable solo and in teams, fluent with technology, and able to distinguish information from expertise. A Google result is not a medical diagnosis. Critical reading and judgment are the future-proof skills.”

Denis Chichmaryov (EPAM) built on that and went straight to the bottleneck: time-to-skills. “Traditional education is slow; industry needs are fast,” he said. The missing bridge is tacit knowledge—the unwritten craft that lives in practitioners’ heads. His proposal: incentivize active professionals to teach, mentor, and co-design micro-curricula with universities. “Lithuania could lead by getting closer to the enthusiasts who spend late nights preparing real trainings and then go deliver them,” he argued. “Let’s stop waiting for someone to change the law. Co-create.”

Marius Skuodis offered a concrete example from the Bank of Lithuania: a quantitative economics program launched with Vilnius University, staffed in part by central-bank experts. The result? A popular, skills-targeted degree that feeds the national financial system with precisely trained talent. “This is what public–private curriculum design looks like when it works,” he said.

Health is not a perk; it’s a productivity platform

Guillaume Hugé reframed health as infrastructure. “Growing economies need healthy people,” he said. Employers can add private coverage and workplace well-being, but the decisive competitive edge comes from system-level access—general practitioners, specialists, and the ability for clinicians to prescribe the latest innovations that keep people at work. He referenced migraine during global awareness week as a cross-generational condition where modern therapies dramatically improve presenteeism. “Countries that speed access to such treatments increase workforce participation,” he said. “That shows up directly in output.”

Sunderman added a relocation-practical detail that often gets missed: in Lithuania, English-speaking medical staff lower friction for global hires. “For a multinational, knowing your people can navigate care easily matters,” she said. From the pharma side, Hugé stressed the complementary piece: research and clinical collaborations with hospitals in Vilnius and Kaunas—the kind of public–private research spine that keeps new therapies and trials close to the talent market.

Government’s new competition: people

Twice during the session the discussion pivoted to a blunt reality: governments also compete for people. Chichmaryov put it crisply: “Every business competes for users. Public services must compete for citizens. Borrow what works—human-centric design, service journeys, feedback loops—and rebuild with the person at the center.”

Several panelists praised International House Vilnius—a “one-stop” hub for foreigners managing residency and related needs—as a model worth replicating in other cities. Sunderman, who recently completed immigration formalities herself, called the experience “professional and humane—strict rules, human touch,” which signals to employers that Lithuania understands the talent on-ramp.

Skoudis added that the state’s role is to clear the runway for high-skill immigration—simple procedures, predictable timelines, and clear information. The market will do the rest: walk through central Vilnius today and you’ll hear “all kinds of languages,” he said. Compared to 15 years ago, the internationalization curve is unmistakable.

The European frame: recruit the continent, not just the country

Van Herwaarden returned to the microphone with a message many in the room nodded along to: think like Europe. “Barcelona didn’t scale because every graduate was a Spaniard with perfect Spanish,” he quipped. “It scaled because Europeans moved there to study and stayed to work. Kraków did the same. Lithuania is equally European—be a talent magnet.”

He tied that logic to internships: bring students in early, test and train them, and convert. “They don’t have to be PhDs,” he said. “Undergraduates and master’s students—normal graduates like me—become your engine if you open the door and invest.”

From knowledge to skills (and how AI changes the math)

A recurring theme—stated by multiple speakers—was the shift from knowledge storage to skills application. “Knowledge is now a service,” Skoudis said, referring to AI’s ability to serve answers on demand. What cannot be commoditized as quickly is critical thinking, adaptability, and the ability to apply insights in messy, real contexts.

Van Herwaarden issued a counter-hype reminder: “Large language models are not intelligence. They connect words; they don’t invent the dot-line between seeds of ideas.” The practical upshot: teach people to reason, to question prompts, to validate outputs, and to compose solutions—not just to retrieve them.

Chichmaryov agreed and translated it into hiring criteria: deep mastery in a home discipline and breadth across adjacent domains—multi-skill sets that can live with uncertainty and still ship. “Speed kills if you don’t have it,” he said, paraphrasing his CEO. Short learning cycles, micro-credentials, and on-the-job upskilling will dominate the next decade.

Sunderman, for her part, pointed out that schools are already aligning: project-based learning, collaborative problem-solving, and digital citizenship are standard, precisely because the future is uncertain and students must be comfortable in ambiguity.

Health access as a competitive differentiator

Returning to health, Hugé made a case for seeing access policy as industrial policy. Allow specialists to prescribe state-of-the-art treatments, reduce time-to-therapy, and you will directly boost output per worker. “The 25–55 cohort is your productivity core,” he said. “If they spend fewer days incapacitated by conditions that modern drugs can control, you’ve created a growth policy without calling it one.”

He also spoke to public–private coalitions that socialize new therapies responsibly, combining payer policy, clinical guidance, and employer programs. The goal is not just compassionate care; it’s a macro-level competitiveness play.

What Lithuania is getting right (and where to push further)

Asked whether Lithuania is on the right path, the panel’s answer was a confident yes—with work to do.

What’s working:

A skilled, multilingual workforce and a visible rise in international hires and returnees.

Early public–private experiments (Bank of Lithuania + Vilnius University; International House Vilnius; research links with Kaunas/Vilnius hospitals).

An ecosystem mindset among companies: internships, internal academies, micro-training, and co-designed curricula.

Where to push:

Speed: shorter procurement-of-people cycles (visas, recognition of qualifications), faster education-to-industry transitions, and micro-credential funding.

Incentives: reward practitioners who share tacit knowledge; co-finance industry-taught modules; expand paid internships.

Health access: upgrade pathways for modern therapies with proven productivity impacts; expand employer–insurer pilots.

Voice: seat youth at the policy table; bring students and early-career workers into FDI strategy discussions.

Practical proposals distilled from the panel

Drawing together the most implementable ideas, here’s a playbook that emerged between the lines:

Stand up a National Micro-Skills Fund

Co-fund short, stackable courses co-designed by employers and universities in AI/ML, robotics, cyber, life sciences ops, and energy transition. Make it easy for workers to stack badges into degrees.Create a “Talent Access SLA” for Lithuania

A published service-level agreement covering visa timelines, qualification recognition, residency steps, and family services (school places, healthcare onboarding). Measure it, publish it, improve it.Pay Practitioners to Teach

Launch Industry Teaching Fellowships that pay engineers, data scientists, clinicians, and product leaders to teach 1–2 courses a year across Lithuania’s universities and colleges.Scale International House

Replicate International House Vilnius in Kaunas, Klaipėda, and Šiauliai. Make it the single front door for relocation, documentation, language support, and spouse employment advice.Health as Growth: Pilot Programs

With payers, hospitals, and employers, pilot fast-track access to therapies with clear productivity gains (e.g., migraine, metabolic disease). Measure presenteeism, publish outcomes, scale what works.Internships at European Scale

Fund pan-European internship funnels to bring EU students to Lithuanian companies for summer placements with conversion bonuses for hires.Youth in the Room

Require each national talent roundtable to include students and under-35 professionals as voting members. Don’t design the future without the future present.

An honest exchange about bottlenecks

Some of the most candid moments came when speakers described the misalignment that still exists between education timelines and industry demand.

Skoudis: “We need to be flexible—modular systems that adapt to shifting needs. LNG taught us that when expertise is built, the world comes calling. Build the next wave in AI, robotics, hydrogen.”

Chichmaryov: “Soft skills for uncertainty and multi-skills are now core. People must stay deep in a craft and broaden across the system. Speed is survival.”

Van Herwaarden: “Let’s teach to think, not only to know. AI doesn’t absolve humans from judgment; it makes judgment more valuable.”

Sunderman: “Belonging is a workforce strategy. Families who feel seen and supported are families who stay.”

Hugé: “Access to modern healthcare is a competitive lever. If you want growth, keep people well and at work.”

Why this matters for investors

For corporate boards and investment committees scanning the Baltics and Central Europe, the panel’s message can be reduced to three investor-centric truths:

Lithuania is building a people-first operating system.

From immigration services to schooling to employer partnerships, the friction around arriving, settling, and growing is steadily dropping. That translates into lower ramp-up risk.The ecosystem already speaks “co-creation.”

Universities and employers are co-teaching; hospitals and companies are co-researching; the city is co-serving newcomers. Investors don’t have to build the bridge alone; they can drive across it and help widen it.Skills are compounding faster than credentials.

Lithuania’s wager—micro-skills, practitioner teaching, internships, and critical thinking—matches what high-velocity firms need. That makes time-to-productivity shorter and retention stronger.

Closing cadence: a country competing on coherence

The panel ended where it began: people. Not abstract headcount, but families, clinicians, teachers, engineers, students—the threads that, woven together, make an economy both resilient and ambitious.

Lithuania’s path is not to out-spend larger neighbors, nor to wait for a demographic miracle. It is to compete on coherence: align education with industry, align health access with productivity, align immigration with on-the-ground services, and align AI’s promise with human judgment. Do those things, and the country won’t just meet investors’ checklists; it will rewrite them.

“Think big. Think Europe. Attract and keep talent,” said Elias van Herwaarden.

“Make the government people-centric,” urged Denis Chichmaryov.

“See health as infrastructure,” pressed Guillaume Hugé.

“Teach for versatility and belonging,” argued Dr. Amanda Sunderman.

“And keep flexibility in the system,” concluded Marius Skuodis.

Smarti.news will continue publishing extended coverage from the Foreign Investors Annual Summit 2025. For speaker interviews, syndication rights, or photo licensing (all images shot exclusively by Smarti.news), contact the Smarti newsroom.

Leave a Comment