19 Minutes

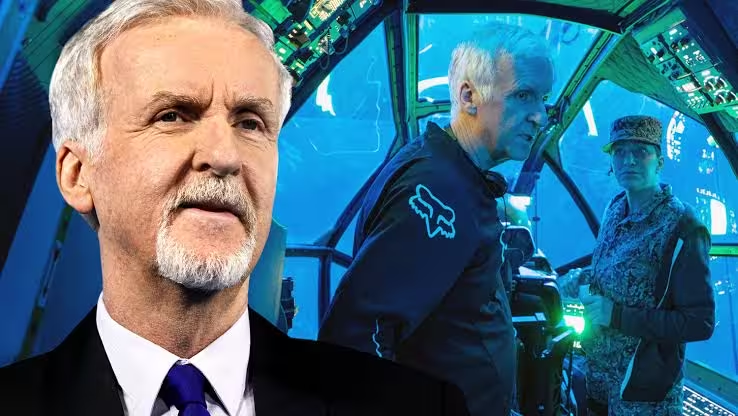

Why James Cameron broke his own rule — and why you should re-watch Avatar: The Way of Water

James Cameron is famously protective of his films in the months and years after they premiere. He often imposes a moratorium on revisiting finished work, preferring the clean distance that lets him be more of an audience member than a hyper-critical director. This time, however, he made an exception. With Avatar: Fire and Ash scheduled to arrive in December, Cameron has been re-watching 2022's Avatar: The Way of Water and preparing its re-release on October 3 — a strategic prelude designed to sharpen audience memory and build momentum ahead of the trilogy's next chapter.

The re-release of Avatar: The Way of Water is more than a marketing play. It’s an invitation to re-engage with the film’s emotional core, to notice the details that set up Fire and Ash, and to appreciate how Cameron and his teams stitched together sprawling family drama, environmental spectacle, and cutting-edge visual effects. The 2022 sequel earned $2.3 billion worldwide; for many viewers it represents an immersive return to Pandora’s oceans, cultures, and conflicts. For Cameron it was a living blueprint that needed revisiting — thematically and technically — to keep continuity across the expanding franchise.

What to watch for on a re-watch: relationships, grief, and the seeds of the next film

If you go back to Avatar: The Way of Water, watch differently. Cameron wants viewers to notice the small narrative signals that pay off in Fire and Ash. Central to his approach is character: Jake Sully and Neytiri are no longer the lone heroes from the 2009 original. They are parents — guardians of a blended family that includes biological Na'vi children, an adopted daughter, Kiri, and a quasi-adopted human boy, Spider. Cameron treats the family dynamic as the beating heart of the saga. Unlike many blockbuster franchises that treat grief as a plot speed bump, he lets sorrow reshape relationships. The death of Jake and Neytiri's eldest son is not a mere trope; it provokes authentic marital strain and long-term consequences that ripple into the third film.

On a technical level, keep an eye on the setups: small camera moves, musical cues, and visual motifs that cue the arcs of Kiri and Spider. Cameron told press he rewatched the film to ensure "thematic consistency about the way music was used and underscore during dialogue scenes." That attention to sonic and visual motifs pays dividends in Fire and Ash, where earlier choices about tone, rhythm, and the emotional palette get amplified.

VFX as storytelling: building a creative culture

One of Cameron’s most striking recent commitments has been reframing visual effects not as a purely technical discipline but as a storytelling craft. He describes an effort to cultivate a "creative culture" among effects supervisors, animators, and lighters: to prompt them to ask not just "how" but "why" a shot exists. The goal is that artists who previously focused on technical fidelity internalize narrative purpose — to think in flow rather than in disconnected shots.

That method produced what Cameron calls "first look finals": VFX shots so complete and narratively resolved that the director can call them finished at a single viewing. For an industry accustomed to 100 or 400 iterations, that’s remarkable. It’s also an argument against a purely automated future in film creation. Cameron has been blunt: generative AI is a tool, but it will not replace artists. He insists artists must be in control of the process — using technology, not being subsumed by it.

This is part of a larger conversation in cinema today. As studios look for ways to reduce costs, AI-driven pipelines promise speed and scale. But the tradeoff — the loss of subtle human decision-making about emotion, rhythm, and cultural nuance — is what filmmakers like Cameron and many VFX supervisors worry will fundamentally change storytelling. For Cameron’s team, the solution has been to blend high-end simulation and novel software with a director’s sensibility and a collective creative approach on the ground.

From technical obsessiveness to narrative empathy

Cameron’s day-to-day VFX instincts are famously granular: the way a foot brushes a fern, the flicker of light on water, the particular way a breath fogs an underwater helmet. Yet stepping back, he says, reveals a larger unconscious driver that determines whether a scene lands emotionally. That paradox — microscopic control married to macro emotional intuition — is one reason Avatar remains a case study in how technical innovation and classical storytelling can coexist.

How the sequels were filmed: an 18-month undertaking and long arcs

Most of the footage for Avatar: The Way of Water and Avatar: Fire and Ash was shot almost simultaneously between September 2017 and mid-2019. Cameron and his cast committed to an intensive 18-month schedule that captured roughly 95% of the material for both films. This marathon approach allowed him to plan multi-film arcs for characters like Kiri (played by Sigourney Weaver’s Na'vi avatar) and Spider (Jack Champion), giving actors room to sustain a trajectory across several installments.

Shooting two films in parallel is a logistical and creative gamble. It ensures continuity of performance — younger characters act as through-lines between films — but it also means the filmmaker sits for years before completing the puzzle. Cameron says the time gap creates "weird cognitive dissonance." Scenes that felt immediate on set may be five or six years old by the time the director returns to them in editorial and VFX review. Actors aged naturally, yet Cameron reports the cast still brings the same passion to press and to new productions.

Reworking scenes midstream: the Toruk example

Even with extensive planning, the sequels were not set in stone. Cameron recounts rewriting and re-shooting when narrative holes revealed themselves during post-production. One vivid example: the Toruk, the great red airborne predator Jake rides in the first film, was something Cameron had been saving for another installment. While watching Fire and Ash cut, he realized Jake needed that mythic moment earlier in his journey. So he rewrote and added two or three scenes, expanding the runtime and restoring a mythic beat. The result lengthened the film — to the surprise of some — but Cameron argues it was the right emotional decision.

The ability to revisit, rewrite, and re-film shows Cameron’s iterative method: make bold long-term plans, but stay flexible enough to course-correct when a character’s truth demands it. That kind of revision is a hallmark of treatment-heavy, director-driven epics — think of the rewrites and rescoring Peter Jackson did across The Lord of the Rings or the decades-long evolutions of Ridley Scott’s science-fiction projects.

What Fire and Ash promises (and how The Way of Water sets it up)

Trailers for Avatar: Fire and Ash highlight Spider and Kiri as central players, indicating a shift toward generational storytelling. Cameron has described the second and third films as telling "one big story" together; the fourth and fifth films are meant to form another paired arc should they get made. This structural planning means that motifs, character beats, and visual language established in The Way of Water will be paid off — sometimes in cathartic triumphs and sometimes in heartbreaking losses.

Cameron’s technique emphasizes nuance over repetition. Instead of two antagonists being locked in endless combat, he enriches conflict by inserting emotional stakes: Quaritch’s resurrection into a Na'vi avatar creates not just a physical enemy for Jake but a competing father figure for Spider. That dynamic turns what could be a flat good-vs-evil struggle into a layered, sometimes morally ambiguous relationship. Cameron has said as much: without Spider in the middle, Jake and Quaritch would be "two guys trying to kill each other for six hours of two movies," which would be thin storytelling. The child bridges the schism; he’s the emotional fulcrum.

Where Avatar sits in the modern blockbuster landscape

Avatar’s focus on family, grief, and indigenous-inspired cultures of Pandora sets it apart from many contemporary tentpoles that rely more heavily on spectacle than on sustained emotional development. When compared with other recent VFX-heavy epics — Denis Villeneuve’s Dune, for instance, or the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s interconnectedness — Cameron is intentionally making something that feels operatic and intimate at once. Where Dune leans into political allegory and the MCU prioritizes kinetic set pieces and serialized payoff, Avatar’s defining characteristic is its worldbuilding coupled with a family drama that asks whether love can survive extreme trauma.

From an industry perspective, Cameron’s approach has become more expensive to sustain. Production and VFX costs have soared in recent years, prompting studios and creators to debate scale versus sustainability. Cameron acknowledges this crossroads. He has other projects in mind — notably an adaptation of Ghosts of Hiroshima — and whether he dives immediately into Avatar 4 and 5 or pauses to explore smaller, personal films will hinge on box-office performance and how the economics of large-scale VFX filmmaking evolve.

Re-release strategies and box office mechanics

Why re-release a recent blockbuster? Studios increasingly use re-releases to refresh public memory and extend the theatrical lifecycle, especially when a high-profile sequel is imminent. Re-releases can stimulate ticket sales, renew interest in franchise merchandising, and generate free press. For Disney and 20th Century Studios, putting The Way of Water back in cinemas ahead of Fire and Ash is a low-risk, potentially high-reward strategy — one that feeds into global awareness and prepares fans for a major December launch.

From a fan’s perspective, re-releases are also communities in motion. Avatar screenings often attract cosplayers, repeat-viewers, and newcomers eager to experience the film on the largest screen possible. That communal energy matters in an age where home streaming offers convenience but not the immersive scale of a theater. If you loved The Way of Water on first viewing, seeing it again in IMAX or Dolby Cinema will likely reveal subtleties in color treatment, sound mix, and motion that a home TV can’t reproduce.

Gen AI, performance capture, and the human element

A recurring theme of Cameron’s comments is his resistance to the idea that generative AI can replace human artistry in cinema. He argues that while AI will be a powerful tool for speeding workflows or generating ideas, the creative choices about what a shot should mean — the emotional weight and narrative intent — remain fundamentally human. The debate around AI has also expanded into ethics and performance: how will we treat digital likenesses, especially of living actors? The controversial cases in the industry over AI-generated performances have underscored the importance of consent, authorship, and creative control.

Cameron’s position is not Luddite; rather, it’s a call to center artists in a tech-augmented future. In practice, that looks like a VFX pipeline that uses simulation and machine learning for grunt work, while designers, animators, and directors continue to make interpretive choices. The "creative culture" he’s cultivating aims to make those interpretive stewards more autonomous and literate in storytelling, so technology amplifies rather than replaces human sensibility.

Behind the scenes: practical choices, performances, and trivia

Fans often ask for set lore. Here are a few behind-the-scenes notes and trivia tidbits that enrich a re-watch:

- Sigourney Weaver’s Na'vi avatar Kiri is written as a teenager across two films; shooting both movies in that 2017-2019 window allowed Weaver to sustain a single arc across the pair, which Cameron says "worked great."

- The production used extended performance-capture techniques underwater — a technological challenge that required training actors to emote while fully kitted in breathing rigs and motion-capture suits.

- Jack Champion’s Spider is the franchise’s human hinge: a character who allows Cameron to explore cross-cultural identity, belonging, and the responsibilities of surrogate fatherhood.

- The Toruk sequence’s late addition shows Cameron’s willingness to reshape scale set pieces when the story calls for it; this willingness is part of what elevates the franchise from a sequence of visually arresting moments to a mythic saga.

Critical perspectives: what works, what doesn’t, and why it matters

No film is beyond critique. Some viewers find Avatar sequels long — Cameron has embraced runtime as a trade for depth. Others critique the franchise for leaning on visual spectacle, arguing that no matter how strong the VFX, a blockbuster must still deliver crisp pacing. Cameron’s counter is that emotional attunement and worldbuilding require time; trimming those layers risks reducing complex characters to archetypes.

There’s also a cultural conversation about representation. Cameron draws inspiration from indigenous cosmologies and environmental themes, but the franchise has faced scrutiny over its approach to cultural borrowing and allegory. These critiques are part of a larger industry reckoning about authorship, appropriation, and the responsibilities of blockbuster filmmakers when they depict cultures inspired by—but not identical to—real-world peoples.

Additionally, the economics of huge VFX films have sparked a debate: can studios keep greenlighting projects with massive budgets and extensive post-production needs? Cameron hints at this dilemma, noting that spiraling costs might necessitate pauses, budget innovation, or new production methodologies to make future Avatar films feasible.

A film historian’s take

"Cameron’s work on Avatar is a rare hybrid of technological daring and old-fashioned storytelling," says Elena Marquez, a cinema historian. "The director’s insistence on artistic control — even through miles of pixels and thousands of VFX layers — ensures that human experience remains central to the spectacle. That’s why re-watching the Way of Water is more than nostalgia; it’s a primer for the emotional logic of Fire and Ash."

How Fire and Ash could shape Cameron’s other projects

Cameron has long said he wants to direct a film adaptation of Ghosts of Hiroshima, a project he insists he will helm at some point. But whether that happens immediately after Fire and Ash will depend on several factors: box-office performance of Avatar 3, profit margins, and Cameron’s ability to innovate cost-effective VFX pipelines. He’s weighing options: take a hiatus to make smaller, personal films; push straight into Avatar 4 and 5 if Fire and Ash is a runaway success; or find a hybrid path where he alternates large-scale epics with more intimate projects.

That crossroads is emblematic of the current industry landscape. Filmmakers who rose in the pre-streaming era must adapt to new financial models, evolving audience behaviors, and the relentless pressure to monetize IP across theme parks, merchandise, and streaming. Cameron’s decisions in the next few years could influence not only his own filmography but also how studios approach multimovie sagas that demand deep VFX investments.

Fan culture and communal viewing

Avatar fans are a vocal community. The re-release will likely reignite forums, fan art, theorycrafting, and cosplay culture. Community reception matters: repeat viewings, especially in premium formats, boost opening weekend numbers for the sequel and signal to studios that a property has staying power. Cameron knows this; the re-release is as much about honoring the fan community as it is about prepping casual audiences for the narrative stakes of Fire and Ash.

Comparisons to Cameron’s previous epics and modern franchise-building

Comparisons are inevitable. Titanic and the original Avatar were both watershed moments for Cameron: Titanic for its emotional sweep and box-office dominance, Avatar for its technological revolution and worldbuilding. With the current Avatar cycle, Cameron attempts to fuse those strengths: the emotional intimacy of Titanic with the immersive technological reach of Avatar (2009). In that sense, the franchise is less about repeating past formulas and more about marrying the director’s lifelong obsessions: epic scale, human feeling, and technical innovation.

Against other modern franchises, Avatar is unusual for its emphasis on continuity and paired arcs. Cameron’s plan to tell stories across multiple paired films (2+3, then 4+5) follows a serialized logic but with the self-contained ambitions of classical epics. If Fire and Ash succeeds critically and commercially, it could reinforce a model where large-scale sagas are crafted as interlocking duologies rather than endless serialized universes.

Practical takeaways for viewers heading back into Pandora

If you’re planning to see Avatar: The Way of Water again in theaters, here are a few tips to get the most from the experience:

- Watch for the emotional cues: music, close-ups, and lingering beats that set up future payoffs.

- Notice Spider and Kiri’s small interactions — they often foreshadow major character decisions in Fire and Ash.

- Experience it in a premium format if you can. Cameron’s films are engineered for scale: immersive sound and larger-than-life screens reveal the micro-details of VFX work and the full breadth of the sound design.

- Bring other fans along. There’s a social pleasure in decoding motifs and sharing immediate reactions after a big scene.

Conclusion

James Cameron’s decision to revisit Avatar: The Way of Water and shepherd its re-release underscores a broader philosophy: blockbuster filmmaking is both craft and community. The biggest technical advances mean little without human direction, and Cameron’s insistence on a creative VFX culture reflects a belief that artists must remain authors even as tools evolve. Whether you return to Pandora for the story or the spectacle, re-watching now promises a richer understanding of the trilogy’s emotional stakes and a sharper anticipation for what Fire and Ash will deliver.

If nothing else, the re-release is an opportunity: to see how modern visual effects can serve nuance, how grief can be cinematic fuel, and how even amid technological change, films still need artists making bold, human choices.

Source: variety

Leave a Comment