4 Minutes

New study links residential SO2 exposure to increased ALS risk

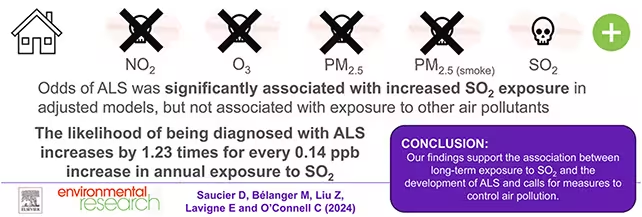

A Canadian case-control study has found a statistically significant association between long-term exposure to sulfur dioxide (SO2)—a common component of fossil fuel emissions—and an elevated risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The research paired 304 people diagnosed with ALS to 1,207 healthy controls of the same age and sex, estimating each participant's pollutant exposure from environmental records tied to their primary residence.

Methods and key findings

Study design and pollutant assessment

The investigators used residential air-quality data to estimate individual exposure histories for several pollutants, with a particular focus on sulfur dioxide produced by the combustion of coal and oil-based fuels. They also evaluated nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and other traffic- and industrial-related emissions commonly linked to neurological and respiratory harms.

After adjusting for socioeconomic and other confounding factors, SO2 emerged as the only pollutant in this analysis with a robust, statistically significant association with ALS. The study notes that higher ambient SO2 levels in the years immediately prior to symptom onset were more strongly linked to ALS than exposures recorded further in the past, implying that harmful processes may accelerate in a relatively short window before clinical diagnosis. The authors reference previous links between NO2 and ALS risk but did not find a meaningful association for NO2 after covariate adjustment in this dataset (Saucier et al., Environ. Res., 2025).

While observational, the link is notable because the regions studied were generally within existing air-quality guidelines, suggesting that even 'legal' concentrations of some pollutants could have previously unrecognized neurological impacts.

Scientific context and implications

ALS is a rare but devastating neurodegenerative disease that destroys motor neurons and leads to progressive paralysis; global incidence is roughly 1–2 new cases per 100,000 people per year. The causes of most ALS cases remain poorly understood: some are associated with genetic mutations and intense physical activity, but a majority arise without a clear family history. Current evidence increasingly supports a multifactorial etiology in which genetic susceptibility interacts with environmental exposures—air pollution among them—to trigger disease mechanisms such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and protein misfolding.

This new analysis strengthens the case for air pollution as one environmental contributor. The study's authors conclude the findings "support the association between long-term exposure to air pollutants, particularly sulfur dioxide, and the development of ALS," and call for tighter pollution controls and prevention strategies to protect public health.

Public health, policy and next steps

From a public-health standpoint, these results argue for revisiting ambient air quality standards and improving emissions controls on fossil-fuel combustion. They also point to priorities for future research: longitudinal cohort studies, finer-scale exposure monitoring (including indoor and occupational sources), and mechanistic laboratory work to clarify how SO2 or its secondary products might damage motor neurons.

Practical measures include expanding community air monitoring, deploying personal exposure sensors in vulnerable populations, and accelerating transitions away from coal- and oil-fired power to cleaner energy sources. As the authors note, prevention strategies and regulatory interventions are essential to reduce population exposure.

Conclusion

The Canadian study adds to growing evidence that air pollution may play a role in neurodegenerative disease risk. Although association does not equal causation, the finding that residential SO2 exposure correlates with higher ALS risk—at concentrations within current regulatory limits—underscores the need for further investigation and precautionary public-health measures. (Saucier et al., Environ. Res., 2025)

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment