3 Minutes

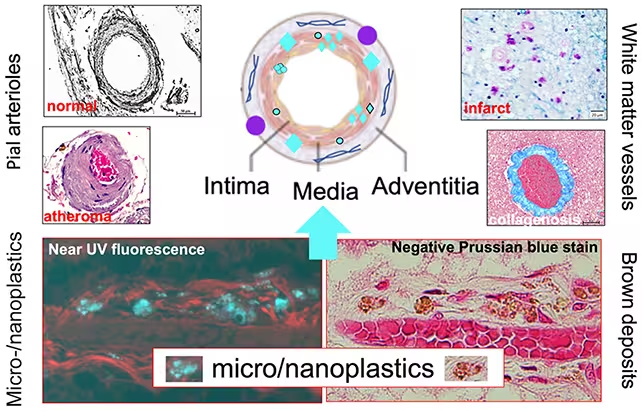

Researchers have detected tiny plastic particles—nanoplastics—inside human brains, and the finding is changing how scientists think about dementia. Early data suggest these pollutants are more common in people with cognitive decline, prompting a fresh look at the biological pathways behind Alzheimer’s, vascular dementia, and other forms of brain disease.

Why this discovery matters

For decades, dementia research focused on hallmark proteins, blood-vessel damage, and genetics. Now, evidence that plastics reach brain tissue introduces a new variable. Lead investigators describe nanoplastics as 'a new player' in brain pathology, and preliminary comparisons show higher concentrations of these particles in people with dementia than in cognitively normal subjects. That correlation, while not yet proving cause and effect, raises urgent questions: do nanoplastics help trigger neurodegeneration, or are they a consequence of tissue damage?

What the science says so far

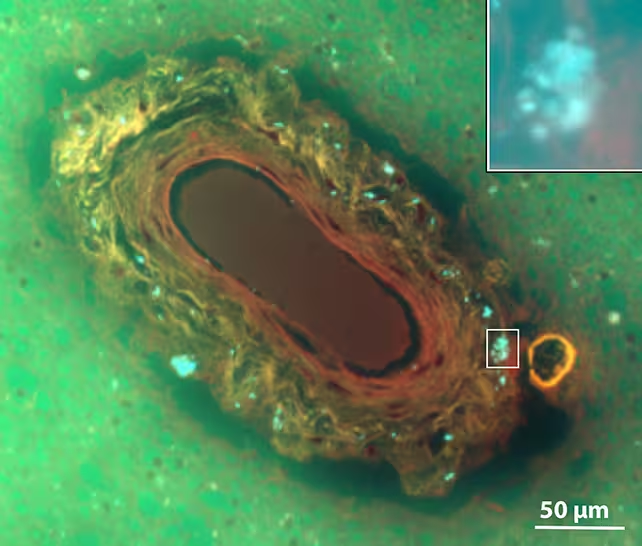

Microscopic plastics originate from breakdown of larger plastic items and from industrial sources. These fragments can circulate in the body, cross biological barriers, and — according to recent pathology reports — accumulate in brain tissue. Researchers note patterns: greater loads of nanoplastics appear to align with certain dementia subtypes and with the severity of disease. This suggests the particles could influence inflammation, vascular integrity, or cellular stress pathways linked to cognitive decline.

Vascular dementia gets re-examined

Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment have been recognized since the late 19th century, but modern diagnostics have shifted attention elsewhere. The presence of nanoplastics offers a new framework for comparing dementia types and for asking why some patients are more vulnerable to brain injury than others.

Implications for research and public health

If nanoplastics play an active role in neurodegeneration, this would affect prevention strategies, environmental regulation, and clinical approaches to dementia. Scientists call for larger studies to map particle types, routes of entry, and biological effects. In the meantime, the finding underscores the need for interdisciplinary work—combining pathology, toxicology, neurology, and environmental science—to understand how pollutants interact with aging brains.

What comes next

Future research will test whether reducing environmental exposure lowers brain burden, and whether therapeutic interventions can reverse particle-related damage. For now, the discovery is a prompt: dementia is more biologically varied than previously thought, and nanoplastics may be a piece of that complex puzzle.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment