6 Minutes

Introduction: Why lymph nodes matter beyond staging

For decades, surgeons have removed lymph nodes during cancer operations to check whether tumours have spread and to reduce the risk of metastasis. Lymph node dissection has been a cornerstone of oncologic surgery for many solid tumours because the presence of cancer in regional nodes is one of the strongest predictors of recurrence. However, recent laboratory research is prompting a careful re-evaluation of this longstanding practice.

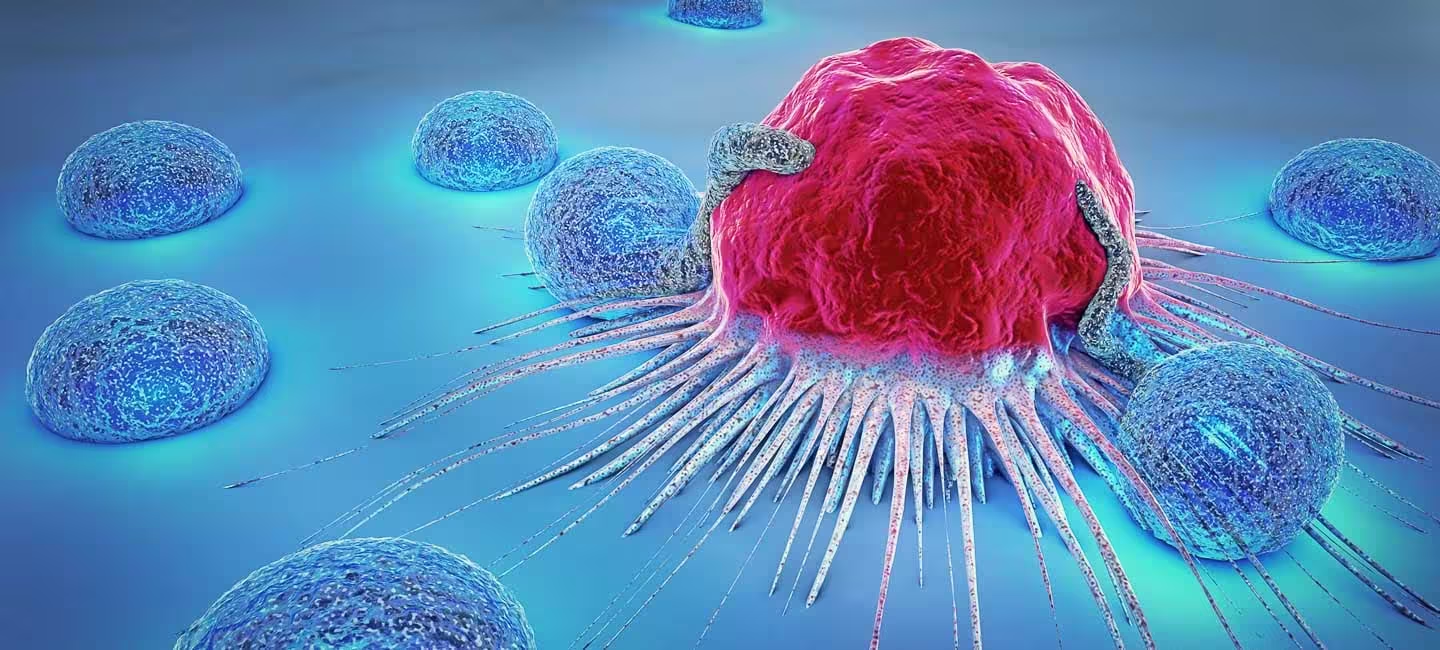

Lymph nodes act as biological filters where immune cells gather, exchange information and mount responses. In immunological terms, they are secondary lymphoid organs that organise the activity of T cells, B cells and antigen-presenting cells. New experimental evidence suggests lymph nodes do more than passively trap migrating tumour cells: they actively prime and sustain specialised anti-cancer immune populations, including CD8+ T cells that can kill tumour cells. This raises a key clinical question: does removing lymph nodes sometimes impair the patient's long-term immune defence against cancer?

How lymph nodes shape anti-cancer immunity

Immune architecture and function

Lymph nodes provide the microenvironment where dendritic cells present tumour antigens to naïve T cells, enabling clonal expansion and differentiation into effector and memory cells. CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes are crucial for recognising and destroying cancer cells. In preclinical studies, components of the lymph node microenvironment—stromal cells, specialized antigen-presenting cells and chemokine gradients—help maintain populations of tumour-specific CD8+ T cells that can be reactivated during immunotherapy.

Recent laboratory experiments in animal models and ex vivo human tissue suggest that removing regional lymph nodes can reduce the pool of these primed T cells and blunt responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Checkpoint blockade (for example, anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies) relies on reinvigorating exhausted T cells; if the lymph node reservoir that sustains those T cells is absent or disrupted, therapeutic benefit may be diminished. Importantly, most of these findings come from controlled laboratory settings—mouse models and tissue studies—and require careful translation before changing clinical standards.

Surgical practice: balancing oncologic control and immune preservation

Why nodes are still removed

Surgeons remove lymph nodes for two primary reasons: staging and local disease control. Pathologic assessment of nodes provides indispensable information for prognosis and therapy selection. For example, sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer identifies the first node(s) draining the tumour and reduces the need for extensive dissections. Removing only the sentinel node(s) lowers rates of lymphoedema (chronic swelling), infection risk and mobility impairment compared with complete nodal clearance.

Yet the new immunology-focused data argue that clinicians must weigh immediate oncologic benefits against potential impacts on the patient's systemic immunity. Lymph node removal can produce well-documented complications—lymphoedema, recurrent infections in the affected limb, and chronic pain—that adversely affect quality of life. The additional concern raised by recent studies is that extensive node removal might weaken long-term immune surveillance, especially when modern cancer treatment includes immunotherapy.

Current trends and risk-reduction

Over the past decade, surgical oncology has shifted toward less invasive, more targeted approaches. Sentinel node biopsies and selective nodal dissections aim to minimise disruption to the lymphatic and immune systems. Where appropriate, non-surgical staging with imaging and percutaneous biopsies can spare patients from node removal altogether. These strategies reduce short-term morbidity and may preserve immune capacity, which could be important when combining surgery with systemic immunotherapies.

Key discoveries and clinical implications

Laboratory teams have identified specific cell types within lymph nodes that support a reservoir of tumour-specific CD8+ T cells. These nodes maintain the cells’ readiness to respond and can seed effector populations that travel to tumours. If translated to patients, the implication is clear: removing nodal tissue indiscriminately might reduce the effectiveness of immunotherapies that depend on these reservoirs.

However, clinical practice cannot be reshaped on preclinical data alone. Randomised trials and observational studies will be needed to assess outcomes for patients who undergo limited versus extensive node removal, particularly in the era of checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T cells and therapeutic cancer vaccines. Meanwhile, multidisciplinary teams must make individualized decisions that consider tumour biology, stage, patient comorbidities and available systemic therapies.

Expert Insight

"Surgery has always been about removing disease while preserving function," says Dr. Maria Alvarez, a surgical oncologist and cancer immunology researcher. "That balance is shifting as we learn more about how the immune system is organised. When feasible, targeted approaches that spare portions of the lymphatic network may improve long-term outcomes by maintaining the compartments that generate anti-tumour T cells."

Dr. Alvarez adds: "We need prospective clinical data to determine which patients benefit from conservative nodal approaches without compromising cancer control. Combining surgical precision with immunotherapy and targeted drugs will be the next frontier in personalised cancer care."

Future directions: personalised node mapping and immune-preserving surgery

Emerging technologies promise more personalised surgical planning. Molecular mapping of lymph node activity—using single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics and advanced imaging—could identify which nodes are essential for immune priming and which are most likely to harbour metastases. Such mapping could enable surgeons to spare immunologically valuable nodes while removing those at highest oncologic risk.

Concurrently, systemic therapies are evolving. Immunotherapies, targeted agents and therapeutic vaccines can potentially compensate for lost nodal tissue by re-educating the immune system or amplifying effector responses. For patients who already have extensive node removal, these treatments may restore some degree of immune surveillance.

Conclusion

The decision to remove lymph nodes during cancer surgery remains complex. Lymph node dissection can be lifesaving and is still a central component of staging and local control for many tumours. But mounting experimental evidence shows that lymph nodes also play an active role in sustaining anti-cancer immunity—especially CD8+ T cell populations that underpin responses to immunotherapy.

The future of oncologic surgery will likely be more nuanced and personalised: combining refined nodal mapping, less invasive surgical techniques and integrated systemic therapies. In the meantime, care teams should discuss the risks and benefits of node removal with patients, considering both short-term oncologic goals and long-term immune health.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment