4 Minutes

In a remote stretch of British Columbia coastline, researchers captured a behavior that challenges assumptions about wolf ingenuity: a female wolf was filmed retrieving a submerged crab trap, hauling it ashore and chewing its netting to access bait. The footage—part of a project to remove invasive European green crabs—may represent the first documented case of potential tool use by a wild wolf.

A deliberate sequence, not a lucky strike

For years, conservation teams working with the Heiltsuk First Nation set crab traps in deep water to catch and remove European green crabs, an invasive species that damages coastal ecosystems. Some traps repeatedly turned up on shore with bait gone, even though they had been deployed in depths that kept them submerged at low tide. Suspecting a marine predator, researchers deployed remote cameras in May 2024 to solve the mystery.

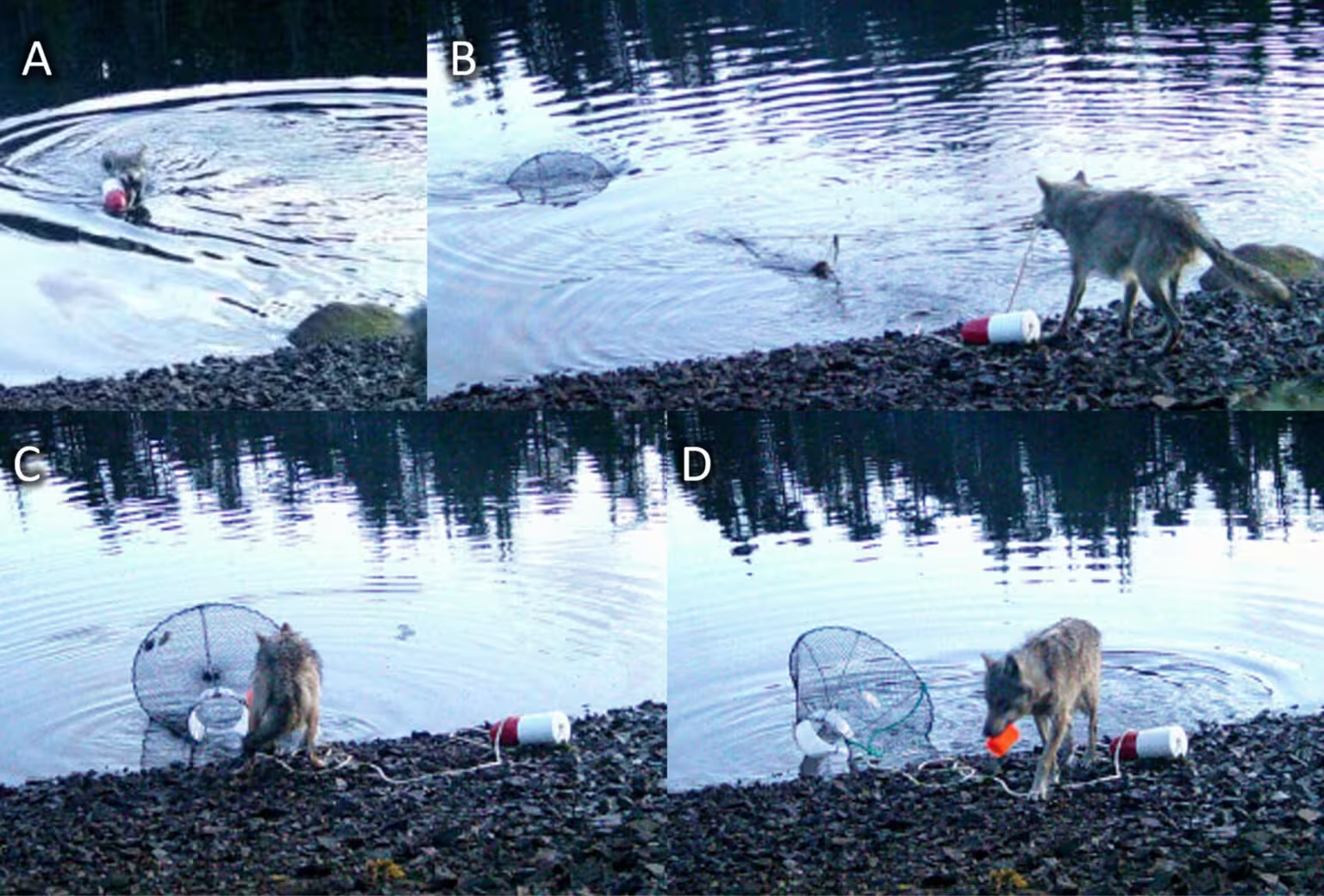

The camera recordings revealed a carefully choreographed chain of actions: a female wolf swam out, seized the buoy attached to a trap, dragged the line and the trap itself onto the beach, then chewed through the netting to reach the baited cup inside.

Stills extracted from remote camera video of a wolf in Haíɫzaqv Territory pulling an initially submerged green crab trap to shore to access the baited cup within. (Artelle & Paquet., Ecology and Evolution, 2025)

Researchers describe the sequence as deliberate and multi-step rather than the rapid pounce we usually associate with predation. Kyle Artelle, an environmental biologist at the State University of New York, said he was stunned when he reviewed the footage, noting that the wolf seemed to recognize the link between float, line and reward and to act accordingly.

Why this could count as tool use

In animal behavior studies, tool use is typically defined as an individual manipulating an object to achieve a goal, such as obtaining food. Classic examples include primates using sticks to extract insects, sea otters using rocks to open shells, and corvids fashioning hooks. If the wolf's actions are interpreted under that framework, towing a trap to shore and exploiting its contents suggests problem solving beyond simple opportunism.

Paul Paquet, a geography professor at the University of Victoria, and colleagues published the discovery in the journal Ecology and Evolution (2025). They are careful to call this the first known potential tool use in wild wolves, emphasizing that more data are needed to determine whether the behavior is learned, widespread, or specific to certain individuals or locales.

Several factors make this setting conducive to such experimentation. Wolves in the remote Haíɫzaqv Territory have limited exposure to humans and fewer immediate threats, which may give them more time for trial-and-error learning. The traps were fixed in deep water and typically inaccessible without deliberate action, so the recorded behavior rules out simple scavenging.

Broader implications for animal cognition and conservation

This observation expands discussions about carnivore cognition and the behavioral flexibility of social predators. It raises questions: Do other coastal wolves exhibit similar tactics? Did the female wolf invent the method, or learn it from conspecifics? And how might such behaviors affect human-led conservation efforts, like invasive species eradication?

Beyond the novelty, the finding is a reminder that wildlife can adapt in unexpected ways when presented with artificial objects in their environments. Researchers suggest continued camera monitoring, collaboration with Indigenous partners, and careful documentation to understand the prevalence and transmission of this behavior among wolves.

The discovery also illustrates the value of combining local stewardship with scientific monitoring: a conservation program designed to protect shoreline ecosystems inadvertently shed light on a new facet of wolf behavior.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment