3 Minutes

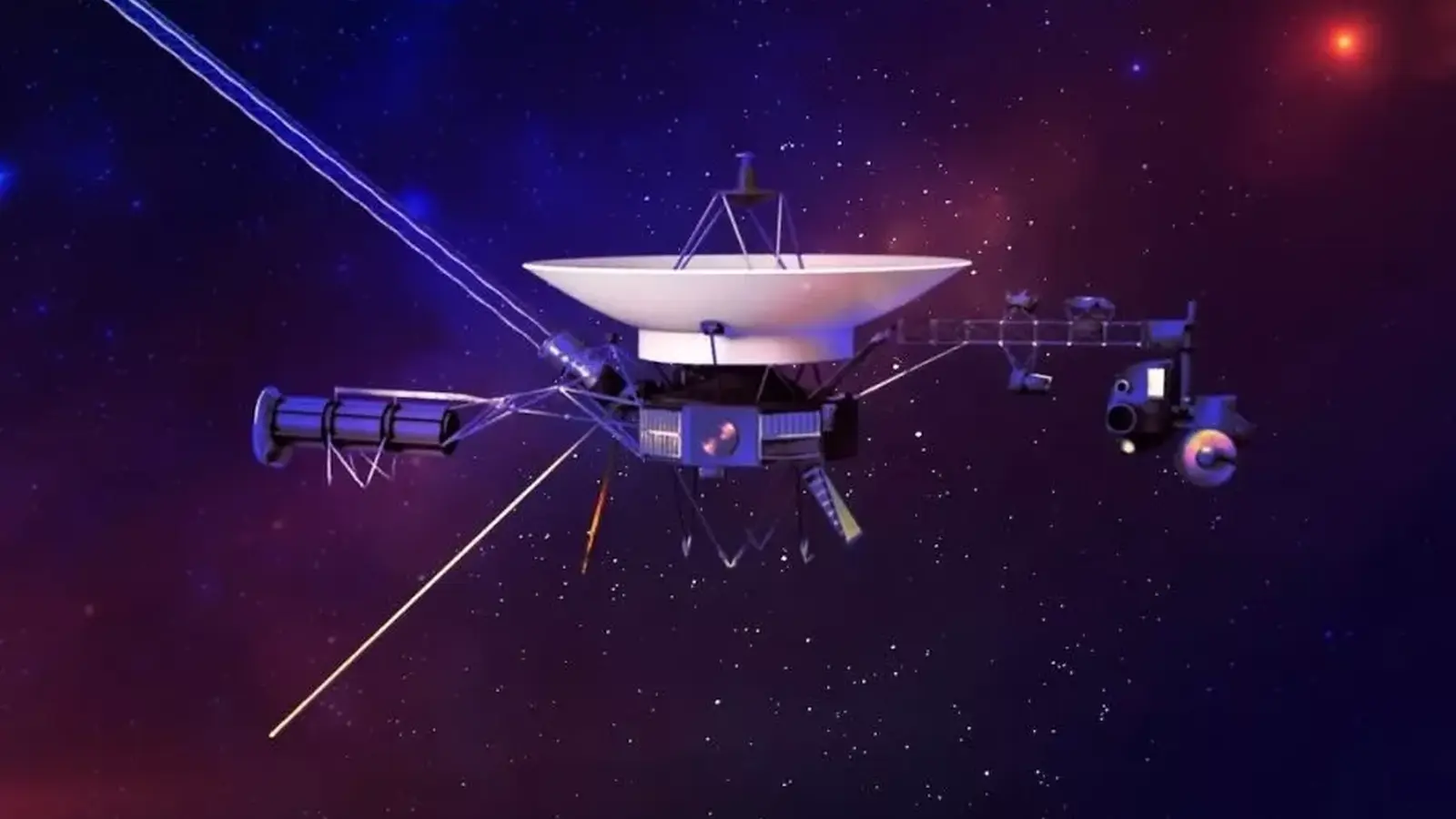

NASA's long-lived Voyager 1 is poised to pass a remarkable milestone in November 2026: it will be the first human-made object to be one light‑day away from Earth. After nearly 50 years in space, the probe will sit so far out that a radio signal traveling at light speed will take a full 24 hours to make the one-way trip.

A simple measure, a cosmic milestone

One light‑day equals the distance light travels in 24 hours—about 25.9 billion kilometers (≈2.59×10^10 km). NASA's trajectory calculations show Voyager 1 will reach roughly 25.9 billion km from Earth around November 15, 2026. Today the spacecraft is already farther than Pluto and drifting deeper into the interstellar medium; current telemetry puts it at about 25.3 billion km away, where one-way radio contact takes roughly 23 hours and 32 minutes.

Why communications become tricky at a light-day

Controllers communicate with Voyager 1 via NASA's Deep Space Network (DSN). Reaching the one light‑day mark transforms routine operations: every command sent to Voyager will take 24 hours to arrive. The probe must then carry out the instruction and transmit an acknowledgment, which takes another 24 hours to return. That means a simple command‑and‑response cycle becomes a 48‑hour wait—two full days—forcing mission teams to plan far further ahead and rely on automated sequences.

How the delay affects science and operations

- Real‑time troubleshooting is impossible; engineers must anticipate outcomes and build robust, autonomous procedures.

- Data downloads remain limited by DSN bandwidth and Voyager's aging transmitter power.

- Long delays change the cadence of science returns—teams will receive updates on a multi‑day schedule rather than hourly exchanges.

From early breakthroughs to a silent ambassador

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 has a legacy of firsts: it was the first human craft to enter interstellar space in 2012, captured the iconic "Pale Blue Dot" image of Earth, and remains NASA's longest-running mission. Its onboard computers and memory are primitive by modern standards—millions of times smaller than a typical smartphone—but they were engineered to be resilient and efficient, and they have delivered decades of discovery.

Voyager's power source, radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), is steadily weakening. NASA estimates the probe will have enough electrical power to run some instruments for roughly one more year or slightly longer before systems are turned off permanently. Even after its instruments fall silent, Voyager 1 will keep coasting through interstellar space as a quiet emissary carrying the Golden Record—an engraved message from Earth bound to drift in the galaxy for eons.

Reaching one light‑day is more than an engineering statistic; it is a reminder of how small our planet is against cosmic distances and of the persistence of human technology. As operations become more constrained by delay and dwindling power, Voyager 1's final active years will demand careful planning and a new kind of patience from the teams on Earth—patience befitting a vessel that has already outlived expectations and become a durable symbol of exploration.

Leave a Comment