6 Minutes

New international research links maternal exposure to PFAS — the long-lasting "forever chemicals" — with subtle structural and connectivity differences in the brains of five-year-old children. The study measured PFAS levels in pregnant mothers’ blood and then compared those concentrations with MRI scans of their children, revealing distinct associations between specific compounds and brain regions.

How the study was done: from prenatal blood tests to childhood MRIs

Researchers from Finland, Sweden and Canada followed 51 mother–child pairs. During pregnancy they measured concentrations of several per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in maternal blood. When the children reached about five years of age, the team performed detailed brain scans to map grey and white matter volumes and to assess connectivity between brain regions.

That paired design — prenatal exposure data matched to later neuroimaging — allowed the scientists to ask whether different PFAS compounds showed unique patterns of association with brain structure. It’s a small cohort, but carefully measured, and the imaging detected several reproducible differences linked to maternal PFAS levels.

Distinct chemical fingerprints in the brain

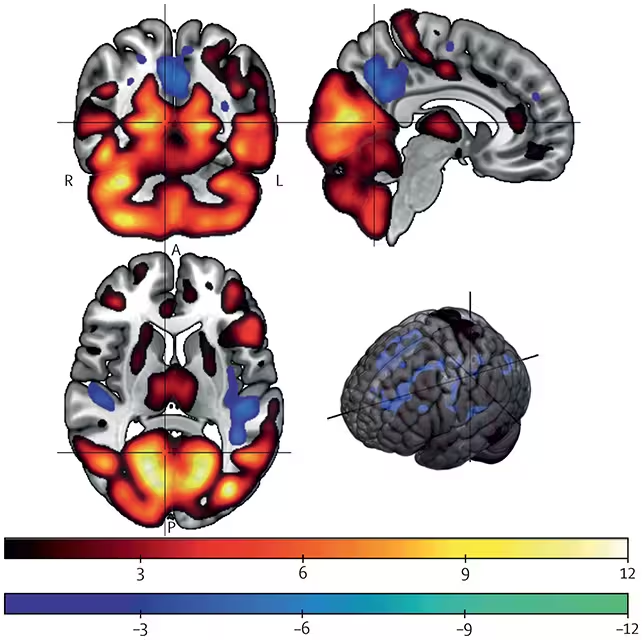

The scans revealed multiple region-specific associations. Two chemicals in particular — perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) — were tied to changes in the corpus callosum, the major white-matter tract that connects the brain’s left and right hemispheres. Other associations appeared in deep brain structures such as the hypothalamus, which regulates metabolism, stress responses and many autonomic functions.

Researchers also reported differences in the volume and surface area of posterior grey matter in the occipital lobe, the brain’s primary visual-processing region. Importantly, not all PFAS behaved the same way: individual compounds had distinct, sometimes opposite, links to the same brain region depending on their chemical structure.

The researchers identified brain changes in children associated with higher levels of PFAS in their mothers' bloodstream. This image shows grey matter volume. (Barron et al., Lancet Planet. Health, 2025)

Why these findings matter — and what they don’t yet prove

PFAS are known to cross the placenta and have been detected in human brains; experimental studies also show they can affect developing brain cells. Still, the current data show associations, not causation. As Hasse Karlsson of the University of Turku notes, "It's unclear whether PFAS are directly affecting brain development — and if so, whether the observed changes lead to harmful, neutral, or even compensatory outcomes."

Tuulia Hyötyläinen, a chemist involved in the study, emphasized the chemical specificity: "We were able to measure seven different PFAS in this study, and found that individual compounds had specific associations with offspring brain structure. In some cases two different PFAS had opposite relationships with the same brain region."

Because the functional consequences are not yet known, experts call for larger cohorts, longitudinal follow-up into school age and adolescence, and combined studies that pair imaging with cognitive and behavioral testing. Only then can researchers determine whether structural differences translate into measurable effects on learning, attention, or other neurodevelopmental outcomes.

PFAS everywhere: persistence, exposure routes and public health

PFAS have been used since the 1950s for properties that repel water, grease and heat. They turn up in nonstick cookware, rain jackets, dental floss, cosmetics and food packaging. Their chemical stability means they can persist in the environment for centuries, accumulating in water, soil, wildlife — and people. Studies have detected PFAS in rainwater, beer and in the blood of nearly all adults sampled in large national surveys.

Exposure pathways include drinking water, food, household dust and occupational contact. "Humans consume PFAS from drinking water, food, or in some cases exposure through occupation," says neuroscientist Aaron Barron. "They are ubiquitous in our blood, and our bodies do not break them down." That ubiquity makes reducing population exposure a major challenge; regulators and engineers are actively testing techniques to remove or destroy PFAS in contaminated water.

What scientists will do next

Future research priorities include expanding sample sizes, tracking developmental outcomes across childhood, and studying mechanisms at the cellular level. Researchers will also probe whether particular PFAS types — for example, longer-chain vs shorter-chain molecules — differ in how they distribute in fetal tissues or disrupt signaling pathways during brain growth.

For clinicians and parents, the immediate takeaway is awareness: PFAS are widespread and can cross the placenta. Public health measures that limit contamination of drinking water and food remain among the most effective ways to reduce exposure at the population level while science continues to clarify health risks.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Rios, a pediatric environmental health specialist (commentary): "This study adds an important imaging perspective to PFAS research. It doesn't yet tell us whether a measured structural difference will impact a child's behavior or learning, but it flags specific brain regions for closer follow-up. Policymakers should take note — reducing PFAS releases and cleaning up contaminated water supplies are sensible precautionary steps while longitudinal research catches up."

The new findings underscore both the scientific complexity and the public-health urgency surrounding PFAS. They show how prenatal chemical exposures can leave detectable fingerprints in a child’s developing brain, and they lay out a roadmap for the larger, longer studies needed to understand what those fingerprints mean for real-world neurodevelopment.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

Armin

Is this even true? 51 mother-child pairs sounds tiny, could be random. Still PFAS are everywhere so worth tracking, but cautious with headlines. more data pls

bioNix

Wow, kinda freaky to see these 'forever chemicals' leave fingerprints in kids' brains… makes me anxious as a parent. Small sample tho, need bigger follow-up, fast!

Leave a Comment