4 Minutes

The North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis), one of the planet's most endangered large marine mammals, appears to be making a tentative comeback. After decades of decline, recent surveys show small but meaningful gains in calf production and overall population size — yet the species still faces acute threats from ships and fishing gear.

A modest rebound: what the numbers show

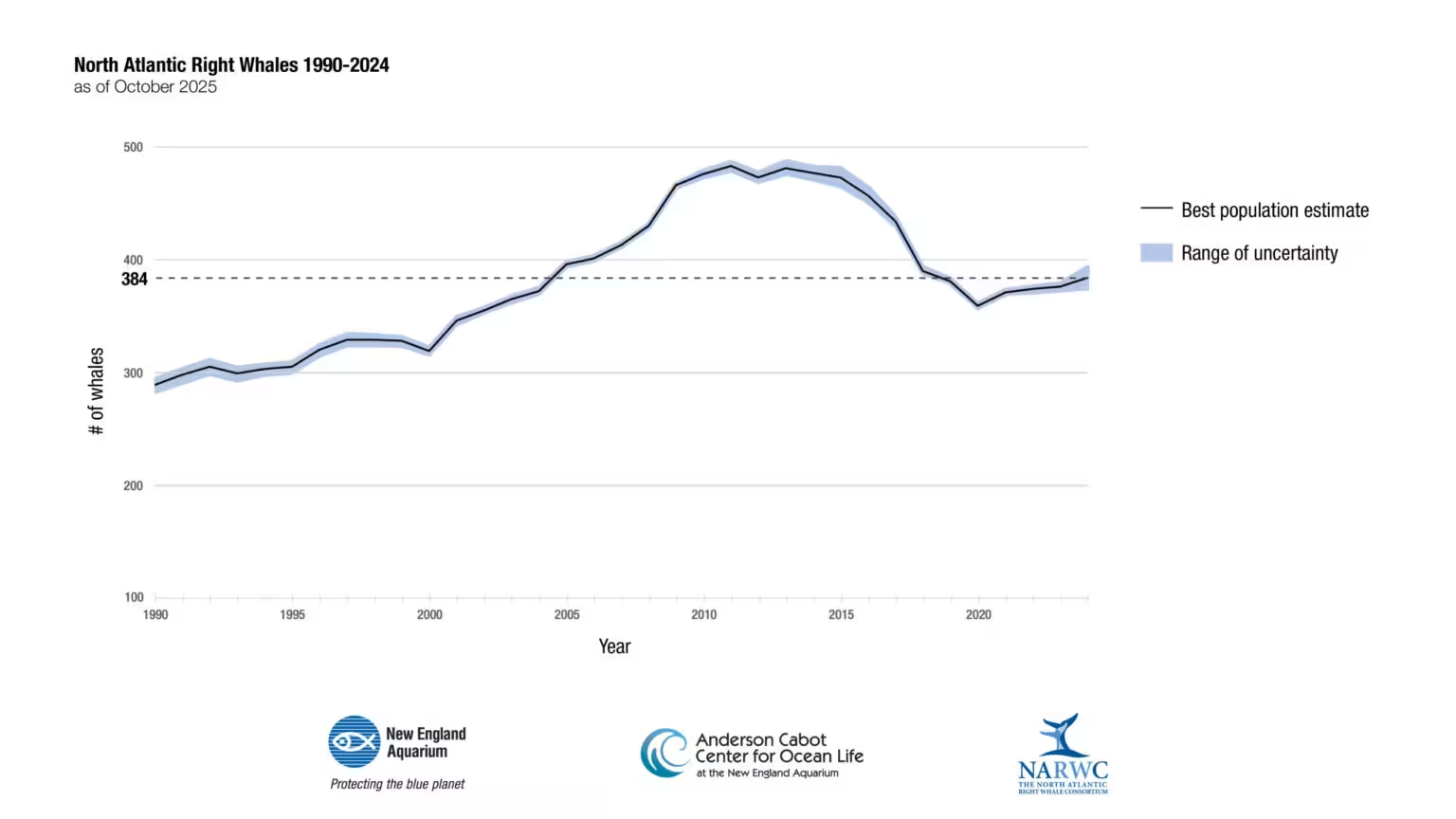

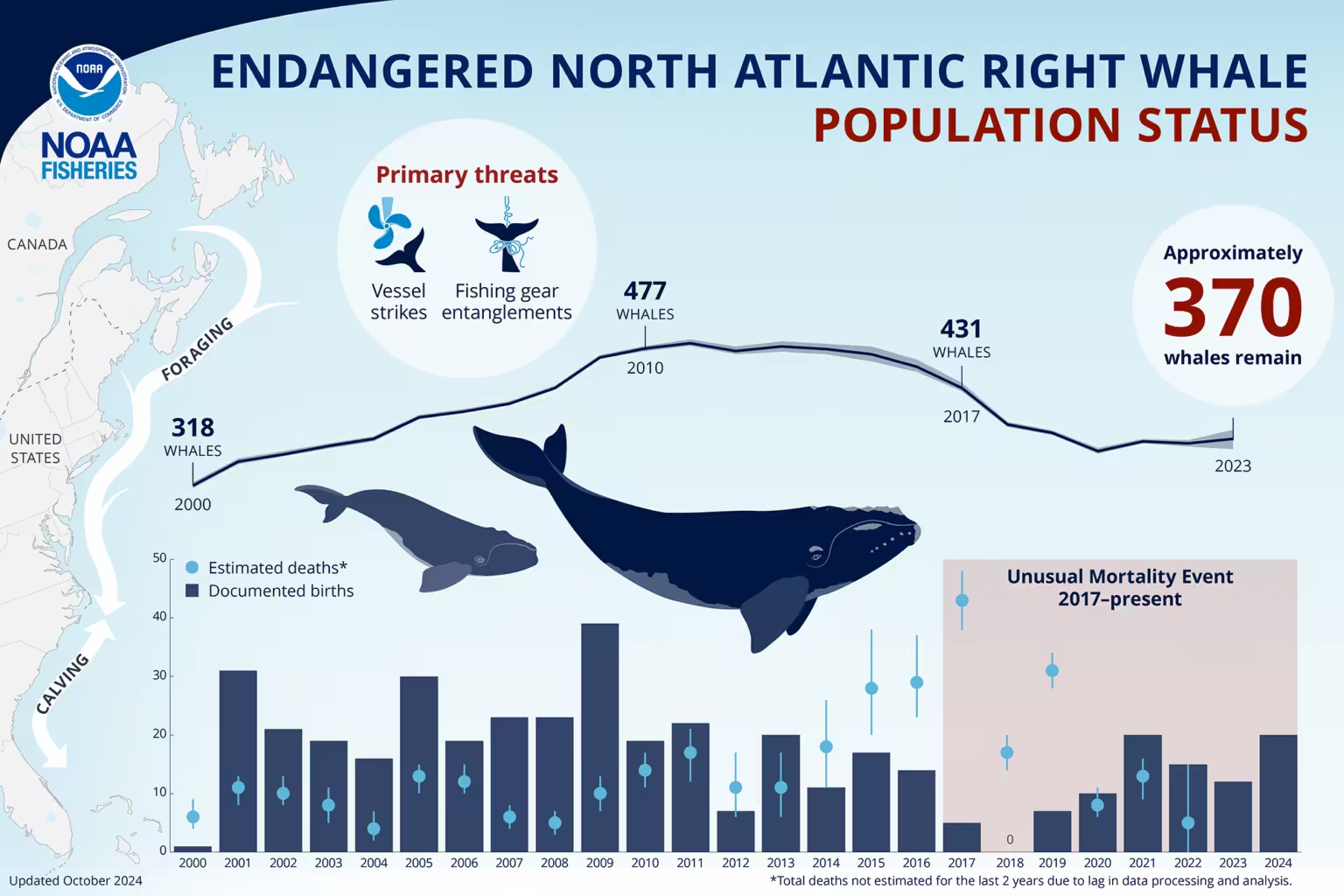

Scientists monitoring the species reported that the population rose by just over 2 percent in 2024 compared with 2023. That increase represents eight newly documented calves and brings the estimated total to roughly 384 animals. It is a small uptick, but it follows a broader trend: since 2020 the population has increased by more than 7 percent after a steep decline in the previous decade of about 25 percent.

These figures come from coordinated surveys and analyses by groups including the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium, NOAA and the New England Aquarium. Population estimates are inherently uncertain for a rare, wide-ranging species, but the recent direction offers cautious hope to researchers and conservationists.

Why recovery is fragile

Despite the positive signal, scientists insist there is little room for complacency. So far in the current year there were no confirmed right whale deaths, but many individuals are still recorded with injuries or poor body condition and birth rates remain lower than historical baselines. For a species that was once hunted almost to extinction — historically considered the "right" whales to hunt because they floated after being killed — even small gains can be easily reversed.

Threats today are mainly human-caused. Vessel strikes and entanglement in fishing gear are the two leading causes of mortality and serious injury. An analysis by the environmental organization Oceana estimated that annually about one quarter of the population in US and Canadian waters becomes entangled in fishing gear, while roughly 85 percent of known individuals have experienced entanglement at least once in their lives.

A North Atlantic right whale with propeller scars

Conservation tools and their limits

Scientists and managers are using multiple tactics to reduce human impacts. Seasonal speed restrictions and dynamic vessel slow-down zones aim to lower the risk of fatal ship strikes. Fisheries managers have also piloted ropeless gear and temporary fishing closures in areas where whales are detected, hoping to prevent entanglements without eliminating livelihoods.

But these measures face practical and social obstacles. Detecting entanglements is difficult because it relies on whales being observed at the right time and place and on observers being present. As Philip Hamilton, a senior scientist at the New England Aquarium's Anderson Cabot Center, notes, detection requires two things to align: people to be looking and whales to be present where they can be seen. Community buy-in, funding for enforcement and technological improvements in fishing gear are all essential to scale effective solutions.

Why this matters beyond the species

Right whales are ecosystem indicators and part of a broader ocean health picture. Their slow reproductive rate and long lifespans mean population recovery takes decades. Every calf matters — and each avoided mortality or serious injury improves the species' odds. The incremental gains of recent years demonstrate that targeted conservation actions can help, but researchers emphasize that persistence, policy support and expanded collaboration with maritime and fishing communities will determine whether this fragile recovery endures.

October 2024 estimates

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment