5 Minutes

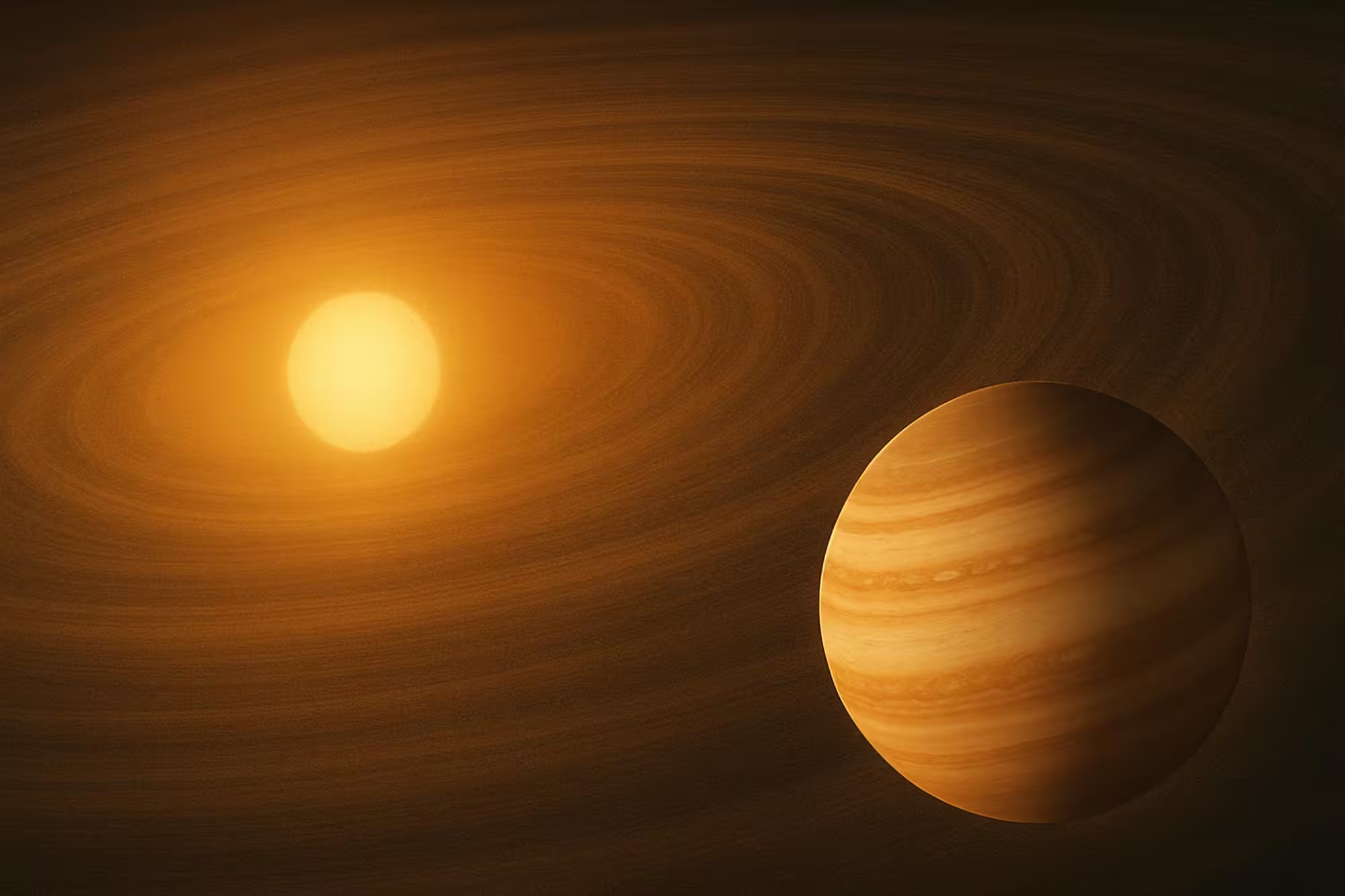

Hot Jupiters — giant planets that hug their stars in blisteringly short orbits — have puzzled astronomers for decades. A new timing-based analysis now reveals that a subset of these worlds likely migrated inward gently through their natal disks, preserving orderly orbits and nearby planetary companions that violent histories would have destroyed.

A new timing-based method reveals that some hot Jupiters followed a calm, disk-driven path toward their stars rather than a chaotic one. Their orderly orbits and stable planetary neighborhoods preserve clues to their origins.

Why hot Jupiters forced a rethink about planet formation

The first exoplanet discovered orbiting a Sun-like star in 1995 was a shock: a Jupiter-mass world completing an orbit in just days. These so-called hot Jupiters are far closer to their stars than Jupiter is to the Sun. The prevailing view is that they formed out at large orbital distances — beyond the system's ice line where gas giants can assemble — and later moved inward. But how they made that journey has been contentious.

Two main migration ideas have dominated discussion. High-eccentricity migration invokes gravitational interactions — with other planets, passing stars, or companion objects — that pump a planet's orbit into a stretched, highly elliptical path. Repeated close encounters with the star then allow tidal forces to shrink and circularize the orbit. Disk migration, by contrast, is a calmer process: the young planet remains embedded in the gas and dust of the protoplanetary disk and slowly spirals inward under drag and gravitational torques.

Timing is everything: a new observational test

Distinguishing those histories observationally has been difficult. Orbital misalignment — the tilt between a planet's orbital plane and its star's spin — can point to a chaotic past, but tides and long-term evolution can hide earlier evidence. To cut through this uncertainty, researchers at the University of Tokyo led by PhD student Yugo Kawai and Assistant Professor Akihiko Fukui developed a timing-based criterion focused on tidal circularization itself.

The core idea is straightforward: if a hot Jupiter underwent high-eccentricity migration, it would have spent a measurable period on a highly eccentric orbit before tides rounded it into the short, circular orbit we see today. That circularization takes time, depending on the planet's mass, orbital period, and tidal dissipation properties. By calculating circularization timescales and comparing them with system ages, the team can test whether there was enough time for high-eccentricity evolution to happen.

What the survey found

Applying this method to more than 500 known hot Jupiters, the researchers identified roughly 30 planets whose circularization times exceed the estimated ages of their systems. In plain terms: these planets are already on circular, short-period orbits, but there hasn’t been enough time for them to have become circular via the long, tidal-driven route implied by high-eccentricity migration. That points to disk migration as the more plausible origin for this group.

Other pieces of evidence support the same story. Many of these timing-selected hot Jupiters show low spin–orbit misalignment, meaning their orbital planes line up neatly with their stars’ rotation. Several also exist in multi-planet systems — a configuration that violent scattering or high-eccentricity episodes would likely have disrupted.

Why this matters for exoplanet science

Isolating hot Jupiters that preserved fingerprints of their formation gives astronomers a laboratory to test models of planet formation and migration. If these planets truly migrated through the protoplanetary disk, their atmospheric chemistry and heavy-element content may retain clues about where they formed in the disk and what materials they swept up on the way inward.

Future directions and observations

Follow-up studies will target atmospheres, composition, and the architecture of these systems. High-resolution spectroscopy, transit timing measurements, and detailed studies of neighboring planets can refine ages, tidal parameters, and orbital histories. Combining timing tests with stellar obliquity measurements and population statistics will sharpen our picture of how common each migration pathway really is.

Expert Insight

"This timing approach gives us a new lever on a long-standing problem," says Dr. Elena Morales, an astrophysicist specializing in planetary dynamics. "By asking whether there was even enough time for a chaotic path to operate, we can separate planets that must have moved gently from those that could have been violently rearranged. That makes subsequent atmospheric and system-level studies far more informative."

Ultimately, combining timing arguments with chemistry and system architecture promises to reveal not just where hot Jupiters ended up, but how they got there — and what that tells us about the diversity of planetary systems across the galaxy.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

Marius

wow didn’t expect disk migration to be this common! kinda cool, makes you wonder what their atmospheres look like now, obs time!!

astroset

Wait so some hot Jupiters slid in gently? Hmm, curious. But how solid are those age estimates, and tides params? Could be underestimated..

Leave a Comment