5 Minutes

Something is ticking deep inside the Milky Way's crowded heart, and astronomers want to know if it will help them rewrite a few chapters in gravity textbooks. That tick — an 8.19-millisecond pulse detected by the Breakthrough Listen Galactic Center Survey — came from a direction very near Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole anchoring our galaxy. If this signal turns out to be a bona fide millisecond pulsar in close orbit, it would be one of the most valuable natural laboratories for testing General Relativity.

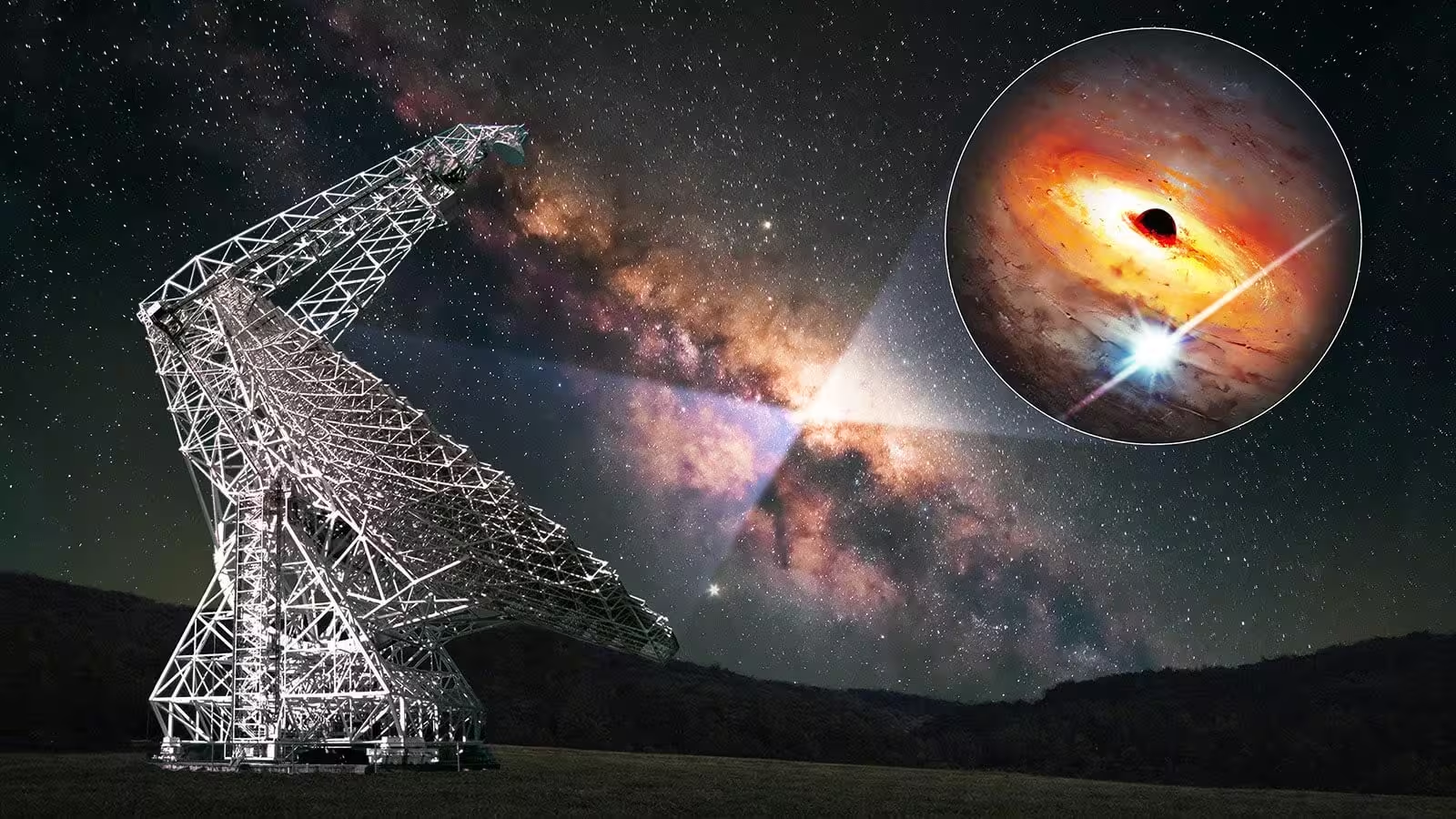

Artist’s impression of the Green Bank Telescope gathering data on the center of the Milky Way. The inset image shows the black hole at our Galaxy’s center, and a nearby candidate (unconfirmed) pulsar.

Pulsars are the collapsed cores of massive stars — city-sized neutron stars packing more mass than the Sun. They spin, and their intense magnetic fields channel radio emission into tight beams. When those beams sweep past Earth, radio telescopes register highly regular pulses. Millisecond pulsars rotate hundreds of times per second. Their timing precision makes them astonishingly stable clocks. A tiny perturbation in arrival times can reveal otherwise invisible influences: orbital companions, interstellar plasma, or the curvature of spacetime itself.

Why a pulsar near Sagittarius A* matters

Imagine placing the most precise clock you own next to a trillion-kilometer gravity well. That’s the promise here. Sagittarius A* has roughly four million solar masses concentrated within a volume no larger than our solar system. General Relativity predicts how spacetime should warp and how light—or radio pulses—should be delayed, deflected, or shifted in frequency when passing near such a mass. A millisecond pulsar in a tight orbit would let astronomers measure effects like the Shapiro delay (a relativistic time delay), gravitational redshift, and potentially frame dragging with unprecedented fidelity. Those measurements would not only test Einstein’s theory under extreme conditions but also probe the immediate environment around the black hole: stellar density, distribution of dark remnants, and scattering by turbulent plasma.

Columbia University researchers, led by Karen I. Perez, reported this candidate in The Astrophysical Journal. Co-author Slavko Bogdanov noted that external influences on a pulsar "would introduce anomalies in this steady arrival of pulses, which can be measured and modeled." In short: tiny timing deviations become big clues.

Follow-up, verification and open data

Detection is only the first step. Pulsar candidates can masquerade as terrestrial interference or transient phenomena. Confirming the source means repeated radio observations at different frequencies and epochs, careful removal of interference, and timing analysis to see whether the 8.19-ms rhythm holds. The Green Bank Telescope, employed by Breakthrough Listen, has the sensitivity to pursue such follow-up. Crucially, Breakthrough Listen has released the observational data publicly so groups worldwide can inspect, cross-check, and apply alternative search algorithms. That openness accelerates verification and invites fresh approaches to de-dispersing and detecting signals through the scattering fog of the Galactic Center.

What happens next depends on what the data reveal. If repeated observations reproduce the pulses with consistent timing and dispersion measures that place the source near the Galactic Center, astronomers will begin long-term timing campaigns. Over months and years, those campaigns refine orbital parameters and tease out relativistic signatures. If the candidate is not confirmed, the data still tighten limits on the pulsar population near Sagittarius A* and guide future survey strategies.

Expert Insight

"Finding a millisecond pulsar so close to a supermassive black hole would be a rare gift to physics," says Dr. Lina Ortega, an astrophysicist who studies compact-object dynamics. "Even a handful of precise timing measurements could distinguish between subtle relativistic models and reveal whether additional unseen masses orbit near the core. It's like switching from a wristwatch to an atomic clock while trying to read the warp of spacetime."

The candidate near Sagittarius A* sits at the intersection of technology and theory: high-sensitivity radio instrumentation, sophisticated signal processing, and decades of relativistic predictions. Whether the object proves to be a millisecond pulsar or an impostor, the search tightens our map of the Galactic Center and sharpens the tools we use to test gravity in its most extreme neighborhood.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

astroset

Whoa, a ms pulsar that close to Sgr A*?? Mind blown... If confirmed, atomic-clock level tests of GR, fingers crossed. Hope it's real not RFI

Leave a Comment