5 Minutes

Parkinson's disease might be whispering through our hair. A recent study from China suggests that a tiny snip could hold clues to a condition long considered hard to pin down early and non-invasively.

The hair clue

Researchers led by biologist Ming Li at Hebei University examined hair samples from 60 people diagnosed with Parkinson's disease and compared them with age-matched healthy controls. Their early, pre-proof report in iScience reports a clear pattern: hair from Parkinson's patients carried lower iron and copper levels and showed elevated manganese and arsenic.

Why hair? Because hair acts like a slow film recorder. It accumulates metals over weeks and months, capturing exposure and metabolic shifts that blood or saliva cannot archive the same way. Blood provides a snapshot. Hair archives history.

The team argues these elemental differences have diagnostic potential. At present, clinicians rely on clinical exams, imaging, and a patchwork of fluid biomarkers to classify Parkinson's disease. A reliable, non-invasive marker that reflects long-term systemic change would be a major clinical advance. But the study is small. Sixty patients can reveal a signal, yes, but not yet a diagnostic rule.

Biology behind the signal

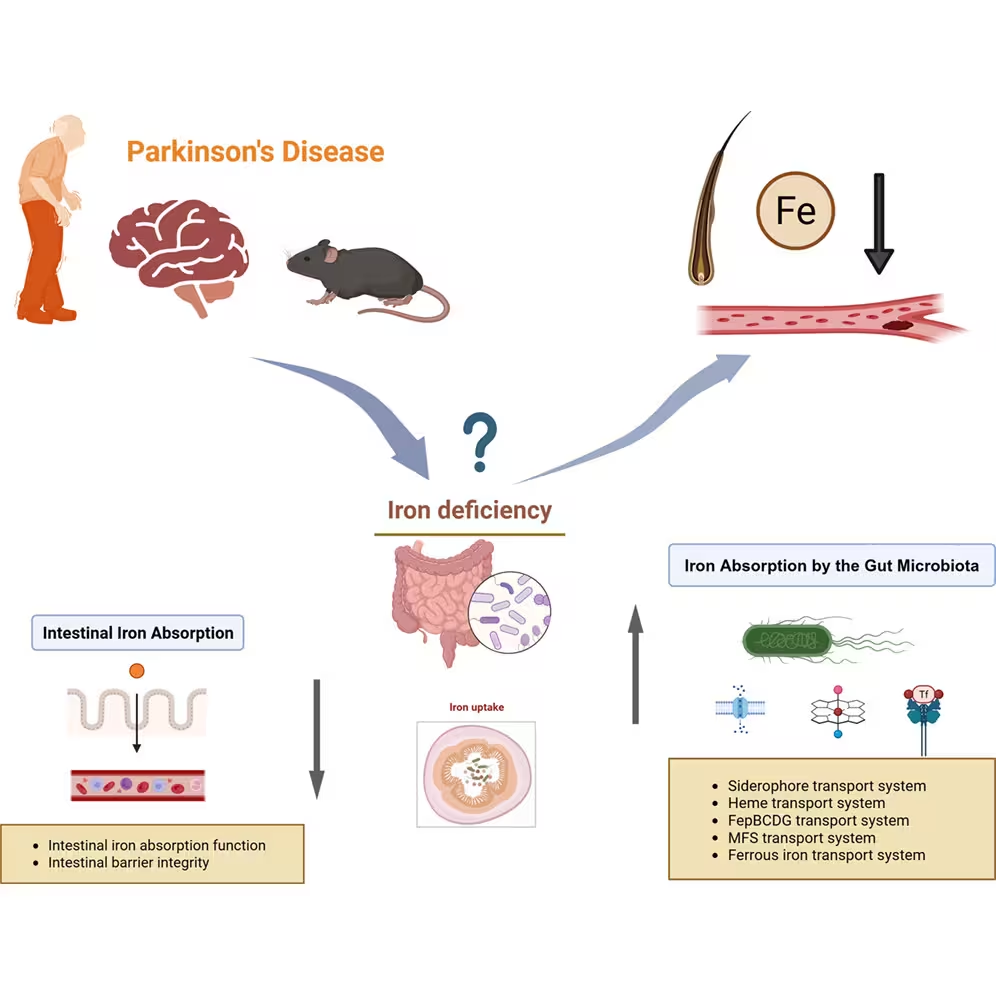

The most consistent observation across human samples and mouse models was reduced iron in hair. In laboratory mice engineered to develop Parkinson's-like dysfunction, low hair iron mirrored signs of gut barrier impairment. Genes that normally help the intestine absorb iron were less active. At the same time, bacterial genes linked to iron scavenging were more active, suggesting microbes might be hoarding iron in the gut and leaving the host deficit-bound.

This paints a plausible biological story. Parkinson's is increasingly seen as a systemic disorder, not solely a brain disease. Changes in gut bacteria often appear years before motor symptoms. Environmental exposures — pesticides, heavy metals, dietary habits — also shape both microbial communities and systemic metal handling. The elevated arsenic in the hair samples is notable here; arsenic exposure can come from food sources such as shellfish and organ meats, which some participants reported eating more frequently, and from contaminated environments.

Iron is central to neural function. Both iron overload and deficiency are implicated in neurodegeneration, depending on where in the body and brain the imbalance occurs. If gut dysfunction and microbial competition reduce available iron for the host, the ripple effects could reach the brain over time. Hair iron therefore may reflect a broader metabolic disturbance tied to disease progression.

Implications and next steps

This line of work follows a 2025 review that compiled evidence for iron dysregulation across the brain, blood, and gut in Parkinson's patients. What the new study adds is an accessible substrate: hair. That accessibility matters for screening in large populations or in regions where advanced imaging and specialized testing are scarce.

However, many questions remain. Can the iron signal distinguish Parkinson's from other neurodegenerative diseases? How much of the hair signature reflects environment versus endogenous metabolic change? And will larger, multi-center cohorts validate the pattern across different diets, water supplies, and occupations?

Expert Insight

"This is a promising needle in a haystack scenario," says Dr. Elena Morales, a neurologist and translational researcher not involved in the study. "Hair gives an integrative readout you can't get from a single blood draw, but we must separate noise from signal. Large, diverse cohorts and careful control for diet and environmental exposure are essential before this becomes a clinical tool."

The path forward is straightforward but painstaking: replicate the finding in larger populations, test whether hair-element patterns predict disease before symptoms, and untangle the molecular chain linking gut microbes, iron handling genes, and neuronal vulnerability. If those steps succeed, a routine hair sample could become part of Parkinson's risk screening, tracking an otherwise invisible system-wide disturbance.

For now, the study offers a provocative glimpse: beneath the routine act of a haircut, a record may be kept — one that tells a longer story about exposure, microbiomes, and the slow shifts that precede neurodegeneration.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment