5 Minutes

Imagine a frontline soldier who, when captured, swallows a grenade rather than reveal the enemy's position. That is the stark choice some immune cells in the brain appear to make when confronting the parasite Toxoplasma gondii: they trigger their own death to prevent the invader from using them as a vehicle.

T cells — especially the CD8+ subset — are best known for hunting infected cells and signaling reinforcements. But University of Virginia researchers have uncovered a more extreme defensive maneuver. When these T cells become infected by T. gondii, they can initiate programmed cell death, a move that destroys the parasite's hiding place and halts further spread through neural tissue.

How a molecular switch forces a decisive sacrifice

At the heart of this suicidal response is an enzyme called caspase-8. Scientists already linked caspase-8 to cell-death pathways, but its specific role inside CD8+ T cells facing T. gondii had not been revealed until now. The research team used genetically engineered mice to remove caspase-8 from targeted cell populations. The result was stark: when CD8+ T cells lacked caspase-8, the parasite spread far more readily into brain tissue despite otherwise robust immune activity.

That finding points to a simple but powerful logic. Toxoplasma survives by living inside host cells. If a carrier cell dies before the parasite can complete its life cycle, the pathogen loses its niche. Caspase-8 acts like a molecular self-destruct button, one that is flipped when infection of the T cell is detected. Without that button, the parasite sometimes gets a ride — a Trojan horse — deeper into the central nervous system.

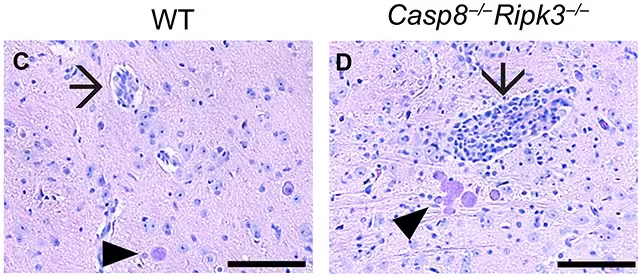

Four weeks after infection, mice without caspase-8 (right) showed higher levels of inflammation than animals with caspase-8 (left). Arrows indicate inflamed blood vessels, and arrowheads indicate T. gondii cysts. (Sibley et al., Sci. Adv., 2025)

Experiment design and what the mice revealed

The investigators compared groups of mice engineered to lack caspase-8 in different cell types against control animals with normal caspase-8 function. Across these tests, T. gondii invaded and formed cysts in the brain much more extensively when CD8+ T cells could not execute the caspase-8–dependent death program. Importantly, inflammatory markers and other immune responses remained strong in those animals, underscoring that the lost protection was not due to a weaker immune system overall but to the absence of this particular defensive tactic.

Why does this matter beyond a curious immunological detail? Because pathogens that persistently infect cells must either tolerate or overcome host cell death pathways. The researchers propose that only microbes able to interfere with caspase-8 — by blocking its activation or downstream effects — could exploit CD8+ T cells as vehicles. That may help explain why T. gondii seems to try this trick only rarely: in most cases, the T cell’s self-sacrifice wins.

T. gondii infects most warm-blooded animals and can persist quietly in human brains for years. Roughly tens of millions of people in the U.S. are estimated to carry the parasite asymptomatically. For healthy individuals this often causes no noticeable illness, but in pregnant people and immunocompromised patients the stakes are higher: toxoplasmosis can lead to severe complications, including damage to the unborn fetus or life-threatening infection in those with weakened immune defenses.

Implications for treatments and immune science

Translating this discovery into therapies will require caution. The current results are preclinical and derived from mouse models; human immune biology has important differences that must be worked through. Still, identifying caspase-8 as a linchpin of T cell–mediated control opens several avenues: better diagnostics for latent brain infections, strategies to protect vulnerable patients, and even targeted drugs that could mimic or enhance this self-limiting behavior of infected T cells.

This work also deepens our understanding of CD8+ T cell function beyond cytotoxic killing and cytokine signaling. It is a reminder that immunity is not only about eliminating invaders but also about denying them opportunities. Sometimes the most effective defense is an uncompromising decision to burn the bridge behind you.

Expert Insight

"The discovery reframes how we think about intracellular pathogens and immune trade-offs," says Dr. Lena Ortiz, an immunologist not involved in the study. "Caspase-8–mediated death in CD8+ T cells is a blunt but effective containment strategy. The next step is to map how pathogens that evade this mechanism operate — that knowledge will point to therapies that either reinforce the cell's decision to die or prevent pathogens from subverting the process."

The study gives a plausible mechanistic explanation for why most T. gondii infections remain silent in healthy people: when immune cells detect infiltration, they are sometimes willing to sacrifice themselves rather than let an intracellular parasite gain a foothold. If future research confirms similar mechanisms in humans, clinicians could one day leverage this knowledge to protect the most vulnerable and to design interventions that preserve delicate brain tissue while controlling persistent infections.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

mechbyte

wow, didnt expect T cells to basically swallow a grenade. wild and kinda brutal. if humans do this too, how do we avoid collateral brain damage? curious..

Leave a Comment