5 Minutes

Imagine an immune system that misreads its own bloodstream as the enemy. Strange, yes. Rare, also yes. But now measurable. An international collaboration of researchers has traced the root of a puzzling, uncommon complication linked to some adenovirus-based COVID-19 vaccines: a molecular misstep that turns otherwise protective antibodies into agents of harm.

From clinical mystery to molecular answer

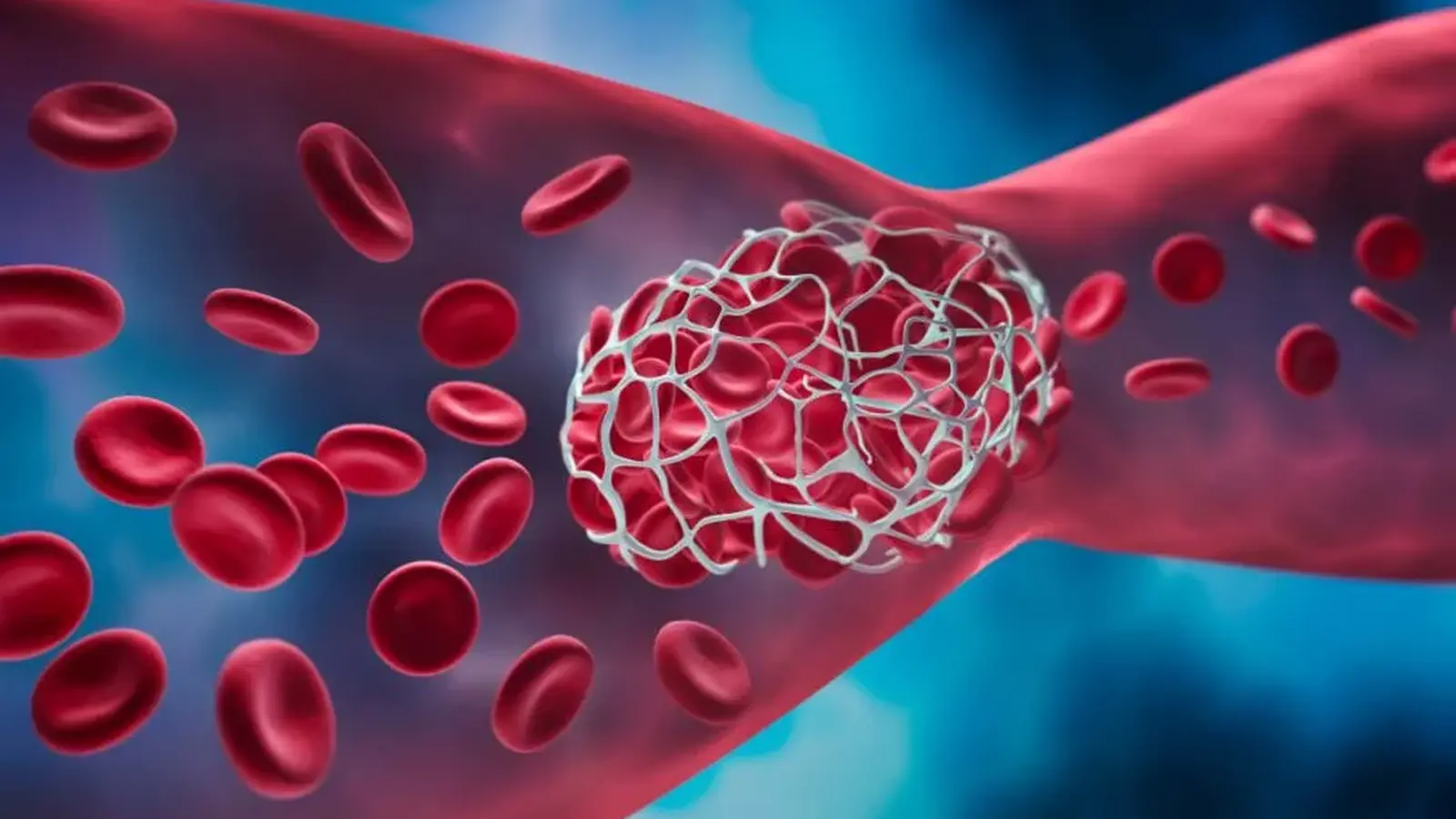

Clinicians and scientists were baffled for months when a handful of patients developed an unusual syndrome combining low platelet counts and dangerous blood clots after receiving certain COVID-19 vaccines. The syndrome—now known as vaccine-induced immune thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (VITT)—was rare, but its severity demanded answers. Teams from McMaster University (Canada), Flinders University (Australia), and the University Medical Center Greifswald (Germany) joined forces and followed the trail from patient blood samples down to single amino acids.

The discovery is elegant in its simplicity and unsettling in its implications. In those rare cases, the immune system produces antibodies that no longer focus solely on the virus-related target; instead, they cross-react with the person’s own platelet proteins and trigger clots. This is not a generic immune overreaction but a precise deviation caused by a specific mutation in the antibody itself and a particular viral protein that nudges the response off course.

"At molecular resolution, we can now see how a normal immune response to an adenovirus can, in extremely rare instances, be diverted," says Theodore Warkentin, the study’s corresponding author and a professor of pathology and molecular medicine at McMaster. "By pinpointing the viral protein involved and a single amino-acid change in the antibody that drives the misdirection, we not only know what happens in VITT but why it happens."

Genes, a single mutation, and a missing explanation

The team found two genetic pieces that matter. First, nearly 60 percent of people worldwide carry a specific inherited antibody-gene variant—IGLV3-21*02 or *03—so the mere presence of that gene cannot on its own explain why VITT remains vanishingly rare. Second, every VITT patient examined carried the same somatic substitution in the antibody variable region: a K31E change that swaps a positively charged amino acid for a negatively charged one.

That swap sounds small. It is. But at the scale of molecular recognition, a single charge flip can redirect what an antibody binds. When the researchers engineered antibodies in the lab and reversed the K31E change, the antibodies lost their clot-triggering capacity. That experiment supplies strong causal evidence: K31E is essential for the pathogenic activity seen in VITT.

How does this misrecognition unfold in the body? The proposed sequence begins with exposure—either through vaccination with an adenovirus vector or natural infection—eliciting an antibody response against a viral protein. In an exceedingly small fraction of immune cells, the antibody gene not only uses the IGLV3-21 allele but also acquires the K31E substitution. The altered antibody now binds both the viral protein and a platelet protein, setting off platelet activation and clot formation.

The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, closes a gap between clinical observation and molecular mechanism. It explains why the same viral platform can be safe for millions yet rarely cause devastating consequences in isolated individuals: both genetic background and a specific somatic mutation must coincide.

Beyond satisfying curiosity, this work has practical reach. Knowing the exact viral component and the antibody change opens pathways for better diagnostics, refined vaccine designs that avoid the problematic epitope, and targeted therapies that neutralize the harmful antibodies without suppressing the whole immune system. It reframes VITT not as a mysterious failure of immunity but as a comprehensible, preventable molecular event.

Science is rarely neat. Still, when a stubborn clinical puzzle yields to careful molecular detective work, the result is more than explanation—it is new leverage to reduce risk and improve public health.

Leave a Comment