8 Minutes

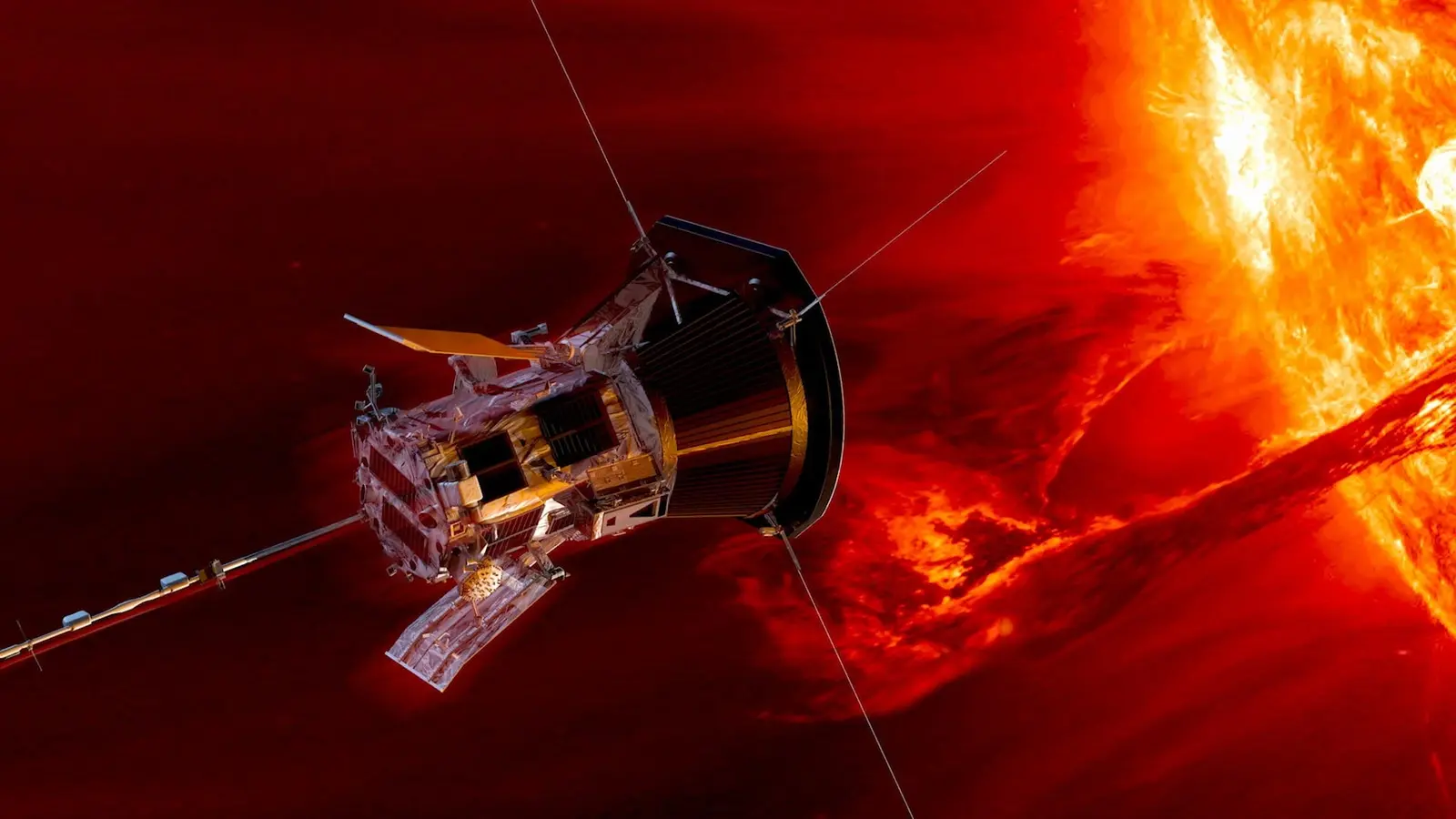

The sun is not a simple furnace; it is a dynamic, magnetic ocean of plasma that keeps scientists arguing, revising models, and occasionally rewriting textbook passages. Parker Solar Probe's closest encounters have handed researchers raw measurements from the sun's immediate neighborhood — data that are forcing a rethink about how the solar wind steals energy and races outward into space. Solar Limb Sensors all over the spacecraft can tell if it’s getting too much sunlight. If one of the sensors gets too much Sun, the spacecraft determines how best to maneuver itself into a safer position.

Probing the point of no return

How does a stream of charged particles, born near the sun's visible surface, end up hotter and faster as it moves away? That paradox — cooler layers below, an ultra-hot corona above — has haunted solar physicists for decades. Parker Solar Probe does not simply skim the surface of this mystery; it dives into the region where the solar wind breaks free from the star's magnetic grip.

This region is more than a boundary on a diagram. It's a place where magnetic fields twist, waves ripple through charged particles, and energy is shuffled, sometimes violently, from fields into particles. During repeated close passes culminating in a near approach on Christmas Eve 2024 — when the spacecraft came within about 3.8 million miles of the sun's surface — Parker has sampled the plasma environment as never before. Those measurements reveal details about particle speeds, directionality, and energy that older, simplified assumptions could not capture.

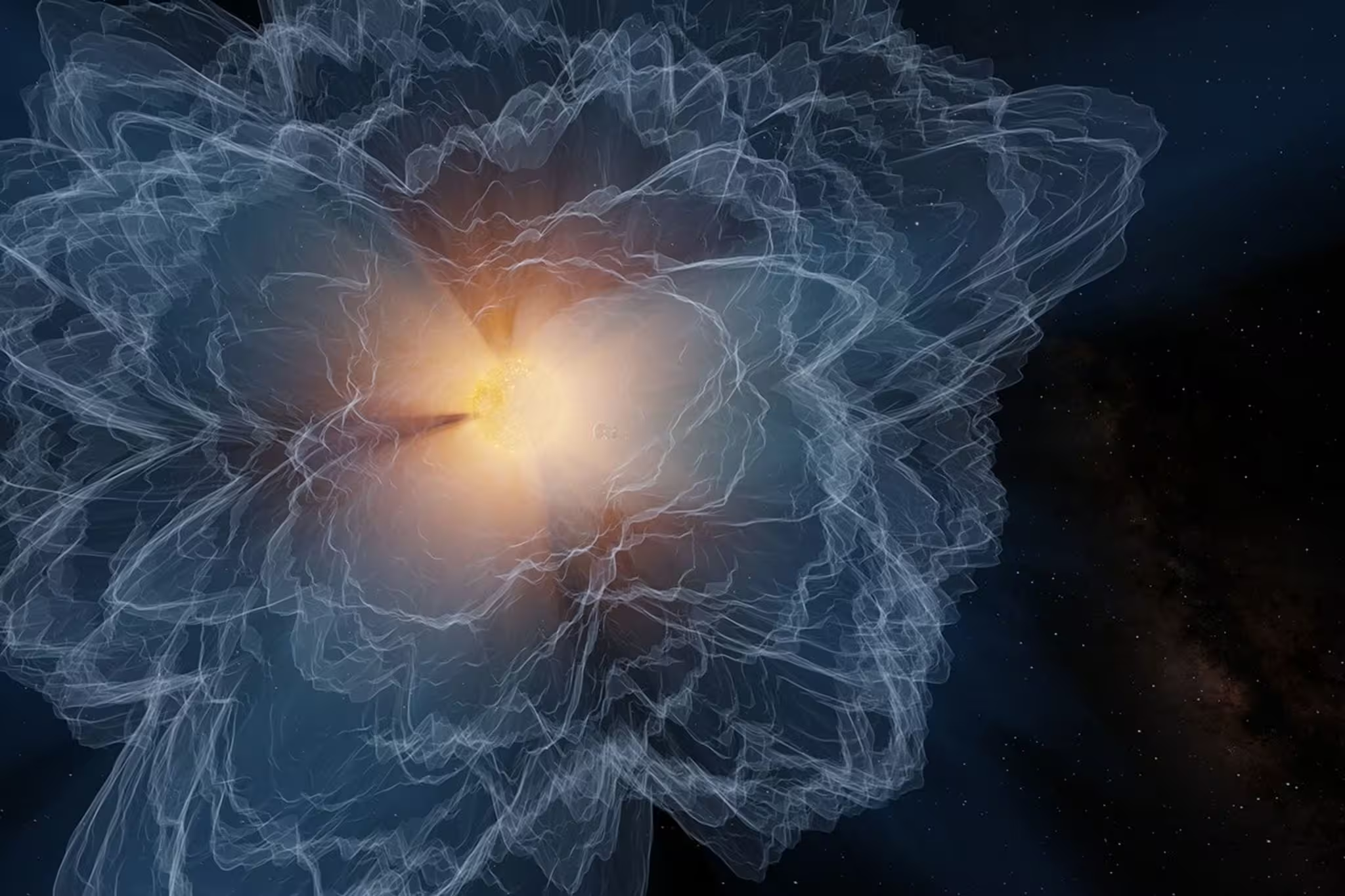

This artist’s concept depicts the boundary of the sun’s atmosphere that marks the point of no return for material that escapes the sun’s magnetic grasp. Deep dives through this area using NASA’s Parker Solar Probe combined with solar wind measurements from other spacecraft have allowed scientists to track the evolution of this structure throughout the solar cycle and produce a map of this previously uncharted boundary.

From raw particle distributions to real physics

Until now, most models treated particle populations as neat, idealized shapes — mathematical conveniences that make equations solvable but can miss messy reality. The new approach embraces messiness: researchers are analyzing the actual velocity distributions measured by the spacecraft. That matters because the way energy transfers from electromagnetic waves to particles depends on those fine-grained details.

Kristopher Klein, who led the analysis, explains the shift plainly: 'We have long suspected continuous heating in the expanding solar wind, but direct measurement of how that heating occurs near the sun changes the conversation.' Their team developed a numerical tool named ALPS, short for Arbitrary Linear Plasma Solver, which reads distribution functions as they are and computes how waves propagate and damp in that real plasma.

Damping. The word recurs because it points to something crucial. As particles stream away from the sun, they would be expected to cool rapidly simply by expanding into space. Instead, Parker's data show a slower cooling — a sign that waves and instabilities deposit energy into particles as they flow. ALPS lets scientists quantify that deposition, tracking which particle species (electrons, protons, heavier ions) gain how much energy and by which mechanisms.

Why this matters to Earth

It is tempting to treat these findings as remote astrophysical trivia. They are not. The heliosphere — the bubble carved out by the sun's outflow — governs space weather across the solar system. Coronal mass ejections, sudden magnetic eruptions that launch billions of tons of plasma, travel through that medium. The manner in which the solar wind heats and channels energy affects how fast and how far those eruptions travel, and how they interact with planetary magnetic fields once they arrive.

'Understanding the sun's atmosphere improves our ability to forecast how eruptions propagate through the solar system,' notes Klein, tying the basic science to real-world risks: satellite disruptions, degraded radio communications, and increased radiation exposure for high-altitude flights. Better physical models reduce uncertainty in space weather predictions, which matters to operators of satellites, power grids, and aviation routes near the poles.

New constraints, new puzzles

Parker's observations do not answer every question — they sharpen it. The team found that energy dissipation in the near-sun wind is neither uniform nor trivial to categorize. Some wave modes transfer energy very efficiently to particular ion species; others produce gradual, distributed heating. The slow cooling or damping seen in particle temperatures suggests a mix of resonant wave-particle interactions and turbulent cascade processes. Untangling these contributions requires more passes, better statistics, and cross-calibration with remote-sensing telescopes and other spacecraft farther out in the heliosphere.

There is also an important takeaway for astrophysics beyond the solar system. Plasmas and magnetic fields shape phenomena from the accretion disks around black holes to the diffuse gas between stars. If we can pin down how energy dissipates in the sun's plasma — an environment we can reach and measure directly — we can transplant that understanding to contexts where direct measurement is impossible.

Mission and methods

Launched in 2018, Parker Solar Probe follows a complex orbit that uses gravity assists from Venus to shrink its perihelion incrementally. Each close pass refines measurements of particle velocities, magnetic field fluctuations, and wave spectra. Combining in situ particle instruments with magnetic sensors and the ALPS solver gives the team a way to convert raw counts and field measurements into heating rates and momentum exchange estimates.

Those tools let scientists test competing theories: is the heating dominated by collisionless damping of plasma waves, by magnetic reconnection events that fling particles into new trajectories, or by turbulent cascades that shuttle energy from large-scale motions down to microscopic scales? Answer: a combination, with relative importance that changes with distance from the sun and with background plasma conditions.

Expert Insight

'These measurements let us move beyond approximations and really confront how energy flows in a collisionless plasma,' says a fictionalized senior heliophysicist, Dr. Elena Ramirez, who collaborates on interpreting Parker data. 'Think of the corona as a crowded market where waves and particles bump into one another constantly — but not by direct collisions like gas molecules. Instead they exchange energy through resonances and fields. ALPS is a new set of ears tuned to those whispers.' Her analogy underlines why direct sampling near the source is transformative: interactions that look negligible from Earth’s orbit reveal themselves close to the sun.

Implications and next steps

Practical benefits are already visible. Improved models can shrink the margin of error in space weather forecasts, making early warnings for satellite operators and power utilities more reliable. Scientifically, the findings demand more refined theories of wave-particle coupling and the conditions under which different dissipation channels dominate.

Parker Solar Probe will continue its deep approaches over the coming years, while ground-based and orbital observatories provide complementary views of the corona and the developing heliosphere. Putting these datasets together is like assembling a stereoscopic image of a previously flat, blurred picture — suddenly structures and motions that were guesswork become measurable quantities.

And the stakes are high: the sun sets the stage for every charged particle in our planetary neighborhood. Read the new maps of that stage closely enough, and you stop being surprised by the props the sun throws your way.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

mechbyte

Is ALPS really solving the messy distributions or is it overfitting the noise? if that’s real then forecasts could improve fast, but hmm..

astroset

Wow, didn’t expect the sun to be such a chaotic place, makes me rethink solar wind models. Crazy data, need more passes tho

Leave a Comment