5 Minutes

Rising Solar Activity: What’s Changed

The Sun, long regarded as a steady and predictable star, is showing signs of systematically increasing activity that researchers did not expect. Official forecasts issued at the end of Solar Cycle 24 in 2019 projected a similarly mild Solar Cycle 25. Those projections have been challenged by observations: Solar Cycle 25 has been more active than anticipated, and a detailed reanalysis of multi-decade measurements indicates a gradual strengthening of the solar wind and related parameters beginning around 2008.

Scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) who examined long-term heliospheric data report steady increases in a suite of solar-wind properties — including speed, density, temperature, thermal pressure, mass flux, momentum, energy, and magnetic field magnitude. These trends point to an upward trajectory in the Sun’s output that is not wholly explained by the familiar ~11-year sunspot cycle alone.

Solar cycle basics and historical context

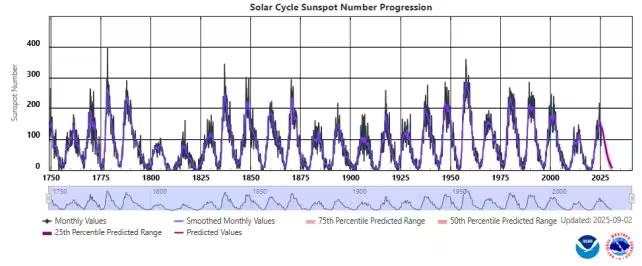

The solar cycle, typically about 11 years from minimum to maximum, governs variations in sunspots, flares, and coronal mass ejections (CMEs). At solar maximum, the number of sunspots rises and the Sun’s global magnetic polarity flips. Sunspot records extend centuries, and they reveal both regular cycles and longer irregular episodes: the Maunder Minimum (roughly 1645–1715) and the Dalton Minimum (around 1790–1830) are examples of prolonged low activity that remain incompletely understood.

A graph showing sunspot activity since 1750

Even with extensive sunspot catalogs, predicting long-term solar behavior remains difficult because much of the Sun’s interior dynamics are hidden from direct observation. Solar cycles 22 and 23 (starting in 1986 and 1996) were conventionally average in sunspot count, yet measurements showed a decline in solar wind pressure across those cycles, prompting some researchers to warn of a possible extended low-activity interval. Instead, Solar Cycle 24 (beginning around 2008) was weak in traditional sunspot metrics, but the underlying solar wind parameters that measure the Sun’s heliospheric influence have been trending upward since that time.

Measurements, interpretations and implications

Researchers analyzing spacecraft records — including near-Earth monitors and data from missions such as NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory, Parker Solar Probe, and ESA/NASA Solar Orbiter — found consistent increases across multiple heliospheric diagnostics. That multi-parameter rise suggests the Sun’s behavior change is not an observational artifact but a real evolution in the heliosphere's state.

These findings are consistent with thinking about solar variability on the 22-year Hale cycle, which groups two successive 11-year sunspot cycles into a full magnetic polarity cycle. Some evidence supports the Hale cycle as the dominant organizing timescale for solar magnetism, meaning that apparent deviations from an 11-year pattern may reflect longer-term, 22-year magnetic processes.

What does increased solar wind strength mean for Earth and space operations? Greater solar wind momentum and larger magnetic field magnitudes can contribute to more frequent or energetic space weather events: stronger geomagnetic storms, enhanced aurora at lower latitudes, increased drag on low-Earth-orbit satellites, and risks to power grids and radio communications during major CMEs and flares. That said, current solar wind pressure remains lower than values recorded near the start of the 20th century, so context and nuance are important: a rising trend does not automatically equal extreme conditions.

Expert Insight

"The surprise is not that the Sun can change — it always has — but that several independent measurements point to a sustained uptick since 2008," says a heliophysics researcher with experience analyzing spacecraft data. "This underlines the need to broaden the metrics we use to characterize solar activity beyond sunspot counts alone."

What scientists will do next

Researchers emphasize continued observation and cross-mission calibration. Combining long-running ground-based records with in situ spacecraft measurements enables a more complete picture of solar dynamics. Missions such as Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter are providing new, close-up views of the solar wind acceleration region and coronal structure, while near-Earth observatories (for example NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center and NASA’s Heliophysics Division) continue to monitor space weather indicators that directly affect technological systems.

The broader implication of the recent analysis is methodological: relying solely on sunspot counts risks missing gradual changes in solar output that affect the heliosphere in other ways. Expanding the catalog of solar measurements — and improving models that connect interior magnetic processes to observable heliospheric effects — will be central to forecasting future space weather and understanding the Sun’s long-term behavior.

Conclusion

Recent analyses show a measurable rise in multiple solar-wind properties since about 2008, challenging expectations that the Sun would remain unusually quiet after the weak Solar Cycle 24. While Solar Cycle 25 has been more active than predicted, researchers caution that predicting the Sun’s future state requires continued multi-instrument observation and improved understanding of magnetic cycles such as the Hale cycle. The trend underscores that sunspot numbers are only one piece of a complex puzzle; tracking the full suite of solar and heliospheric variables is essential for anticipating space weather impacts on Earth and technology in orbit.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment