5 Minutes

The discovery of a strange planetary lineup around a nearby red dwarf has scientists rubbing their eyes. One small, rocky world sits close to its star. Two gas giants follow. And then—unexpectedly—another rocky planet lies farther out, where gas should have dominated. Simple. Strange. Compelling.

The odd architecture of LHS 1903

A team of international astronomers, analyzing measurements from multiple observatories and Europe’s Cheops space telescope, reported the pattern in a new paper in Science. The system orbits LHS 1903, a red dwarf tucked into the Milky Way’s thick disc. Red dwarfs are cooler and dimmer than the Sun; they are also the most common stellar type in the galaxy. Yet frequency doesn't mean predictability.

Thomas Wilson, lead author and planetary astrophysicist at the University of Warwick, described the arrangement bluntly: rocky, gaseous, gaseous, rocky. "That makes this an inside-out system," he told colleagues. "Rocky planets don't usually form so far away from their home star."

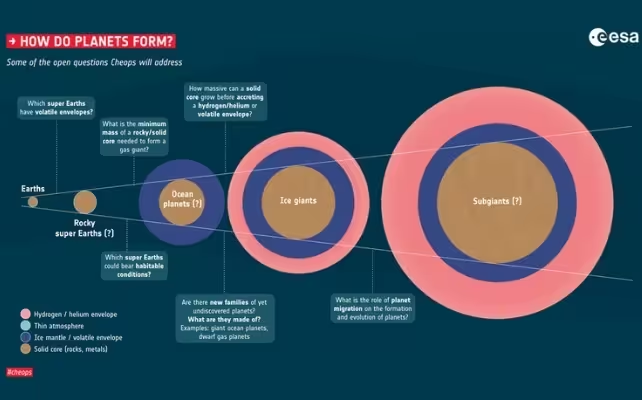

Why not? Near a star, intense heat and radiation strip light elements from emerging worlds, leaving behind dense, rocky cores. Farther out, cooler conditions allow cores to accumulate thick gaseous envelopes and grow into gas giants. That tidy radial pattern—small rocky bodies inside, large gas giants outside—has shaped centuries of theory since astronomers mapped our own Solar System.

Graphic showing the order of planet formation. (ESA)

Rethinking formation timing and local conditions

When the LHS 1903 team ran through the usual explanations—migrating planets, capture, measurement errors—those ideas fell short. Instead, they settled on a counterintuitive scenario: the planets may not have formed all at once. What if formation was staggered?

Standard models picture planets growing at roughly the same time inside a sprawling protoplanetary disc of gas and dust. Dust grains collide, clump, and build up into cores that either keep their gas to become giants or remain bare and rocky. In LHS 1903's case, the inner worlds might have accreted while the disc still brimmed with gas. By the time the outermost planet formed, the local reservoir could have been depleted—leaving a planet that is small and rocky despite its distance.

An artist's concept of a protoplanetary disc. (JPL-NASA)

"It seems that we have found first evidence for a planet that formed in what we call a gas-depleted environment," Wilson says. If confirmed, that would force a modest revolution in how astronomers model planet formation: not all protoplanetary environments are homogeneous or long-lived, and timing matters as much as location.

The discovery leans on transit photometry and follow-up observations. Cheops provided precise measurements of the outer planet's radius, crucial for determining whether it is gas-rich or gas-poor. Combined with mass estimates and orbital dynamics, the data paint a rare and clear picture: an outer, small-radius world where one would normally expect bloated gas envelopes.

Isabel Rebollido, who studies planetary discs at the European Space Agency, noted that our theories have long been anchored to the architecture of the Solar System. "As we catalog more exoplanetary systems, we are forced to revisit assumptions rooted in a single example," she said. The universe has been quietly more inventive than we gave it credit for.

Implications and future tests

How does one odd system translate into revised theory? Not overnight. But LHS 1903 provides a concrete case study: models must accommodate local gas depletion, variable disc lifetimes, and sequential planet assembly. Simulations that add time-dependent gas removal, or include stronger star–disc interactions, may reproduce inside-out patterns more readily.

Observationally, astronomers can seek siblings. If other systems show rocky planets at unexpectedly large separations, a pattern will emerge. More precise mass and atmospheric measurements—especially with JWST and upcoming telescopes—can reveal whether outer rocky worlds are bare cores or possess thin, secondary atmospheres that hint at a different formation history.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maya Alvarez, an astrophysicist specializing in disc evolution, says: "LHS 1903 is a timely reminder that planet formation is not a single script. Discs evolve unevenly. Gaps, winds, and photoevaporation can clear gas locally; once the fuel is gone, the chemistry and outcome of planet building change. This system gives theorists a real constraint to test against, not just a curiosity to admire."

Beyond academic appetite, this matters for habitability studies too. The composition and atmosphere of a planet depend heavily on how and where it formed. An outer rocky planet formed in a gas-starved region could have very different volatiles and prospects for water than an inner rocky world.

In short: the cosmic assembly line may be messier and more episodic than we assumed. LHS 1903 is a small system with outsized lessons—if we pay attention, it will reshape questions more than answers for a while yet.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment