6 Minutes

She was a marathon runner in her mid-30s. Then came a persistent ache in the knee that would not quit. Jokes about creaky joints gave way to X-rays and a diagnosis: stage 2 osteoarthritis. That story is no longer an outlier. Clinicians and researchers are seeing the disease in increasingly younger, active people — and that shift raises uncomfortable questions about prevention, diagnosis, and long-term care.

Why osteoarthritis is showing up earlier

Most of us think of osteoarthritis as the price of getting older. But age is only one factor. The condition emerges when the cartilage that cushions a joint wears down, allowing bone to grind on bone. Simple enough in description. Complex in reality. Obesity, previous joint injuries, repetitive mechanical stress from sports or labor, chronic inflammation, and metabolic conditions all accelerate the process. The result? A wider and younger patient population confronting pain, stiffness, and the limits those symptoms place on work, family, and exercise.

Consider the life-course impact. A person diagnosed at 35 may spend decades managing pain, alternating between physiotherapy, injections, and — in time — joint replacement. That is not simply an orthopaedic problem. It ripples into mental health, career choices, physical fitness, and the risk of secondary conditions like cardiovascular disease. The emphasis, then, must shift from reacting at late stages to spotting risk early enough to change the arc.

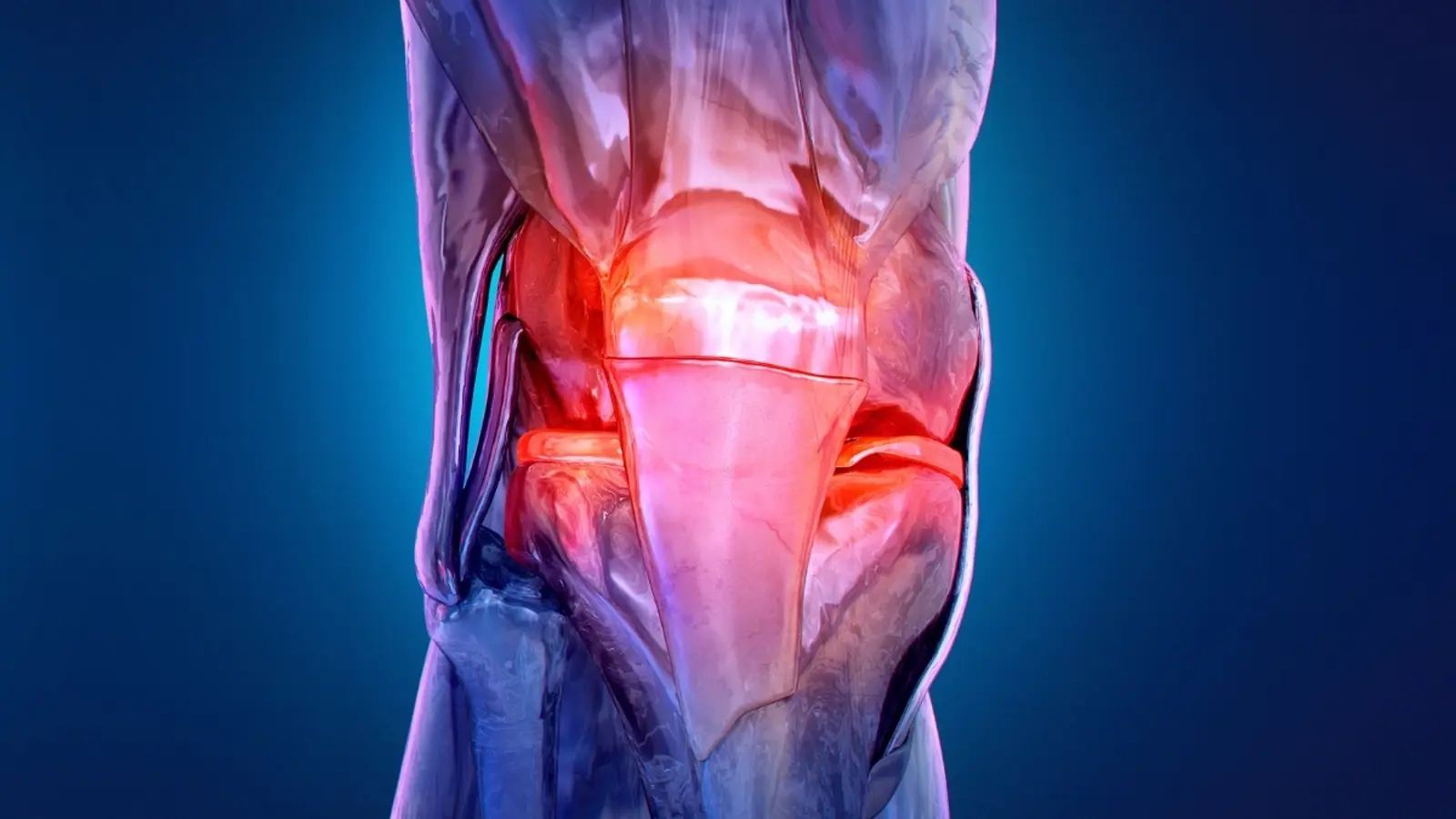

What happens inside the joint

Cartilage acts like a well-engineered shock absorber. It lets bone surfaces glide with little friction. As cartilage thins and fissures, biochemical changes follow: increased local inflammation, altered tissue turnover, and shifts in the molecules bathing the joint. Patients often first notice subtle signs — mild pain after activity, transient stiffness that fades with movement, or the odd crunching sensation. Those early cues are easy to ignore. By the time persistent pain prompts imaging, structural damage can be advanced.

Treatment today is pragmatic and symptom-focused. Exercise therapy aims to strengthen surrounding muscles and restore function. Pain control ranges from oral analgesics to targeted injections. Platelet-rich plasma injections, harvested from a patient’s own blood, deliver a matrix of growth factors intended to nudge repair processes. Hyaluronic acid injections seek to restore lubrication. Researchers are also studying platelet-derived vesicles — microscopic packages of signaling molecules — but most of that evidence is still preclinical, often in animal models. These approaches can relieve symptoms; few reliably reverse established cartilage loss.

Emerging paths to earlier diagnosis

What if we could detect the disease before pain becomes relentless? That prospect is the focus of several laboratories exploring molecular signatures in blood and joint fluid. Every molecule leaves a trace. When those traces are read en masse they form a kind of spectral fingerprint of health and disease.

How spectroscopy reads chemical fingerprints

One technique gaining attention is attenuated total reflection Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Say that quickly and it sounds like jargon. In plain terms: a tiny blood sample is bathed in infrared light, and the pattern of light absorption reveals the mix of proteins, lipids, and metabolites present. Subtle shifts in those patterns may reflect early inflammation or changes in tissue turnover associated with osteoarthritis. Combine that biochemical readout with machine learning and complex patterns become detectable — patterns that human eyes would miss.

Other molecular tools and biomarker assays complement spectroscopy. Researchers compare large cohorts of samples from people with and without joint disease, then search for reproducible differences. The hope is pragmatic: identify a fingerprint that predicts risk, so clinicians can intervene with targeted exercise programs, weight management, injury prevention, or early-onset therapies when they matter most.

Early detection would not simply reduce pain; it could bend the lifetime trajectory of disease and lower long-term healthcare burdens.

Technologies, trials, and the path ahead

Many of these approaches remain in research settings. Translating a promising spectral signature into a validated clinical test takes time: reproducibility, standardization across labs, large prospective studies, and regulatory review. Yet the convergence of better molecular assays, accessible spectroscopy platforms, and computational power gives reason for optimism. Add wearable sensors and smarter rehabilitation programs, and you begin to imagine a future where risk is managed long before the joint is damaged beyond repair.

There are practical considerations, too. Who should be screened? Athletes with recurrent joint injuries? People with metabolic syndrome? Workers in physically demanding jobs? Cost-effectiveness will determine how broadly early diagnostics are deployed, and ethical frameworks will be needed to translate risk scores into care plans without causing undue anxiety.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maria Chen, a clinical rheumatologist and investigator in musculoskeletal diagnostics, says: 'We are finally learning to listen to biochemical whispers before the joint shouts. Early markers won't replace clinical judgement, but they will change when and how we act. Small interventions at the right time can preserve function for years. That matters more than any single drug.' Her view captures the pragmatic optimism behind current research: incremental gains that compound over a lifetime.

For now, clinicians balance symptom relief with lifestyle measures that protect joints: tailored exercise, weight control, sensible return-to-play decisions after injury, and attention to metabolic health. The research community continues to refine biomarkers, validate spectroscopy methods, and explore biologics that might one day move beyond symptom control to true tissue preservation.

Osteoarthritis in younger adults is a wake-up call. It nudges medicine away from the late-stage cycle of pain and replacement and toward prevention, early detection, and long-term stewardship of joint health. That transition will require better tools, smarter screening, and a shift in how society thinks about musculoskeletal health — especially for people still in the busiest chapters of their lives.

If you have persistent joint pain, seek assessment sooner rather than later. Early steps can make a lifetime of difference.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

labcore

Wow didnt expect this. Ran marathons at 34, knee started aching... scary. Early checks, folks, don't ignore it

Leave a Comment