5 Minutes

Imagine waking up dozens of times a night because your airway collapses. Imagine doing that for years. For many people with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), this is reality: interrupted sleep, daytime fog, and a raised risk of heart disease and cognitive decline. A new, far less invasive twist on hypoglossal nerve stimulation—tested by researchers at Flinders University—offers a strikingly simple solution: a tiny electrode, placed quickly and guided by ultrasound, that nudges the tongue out of the way and reopens the airway.

How the device works and what the trial showed

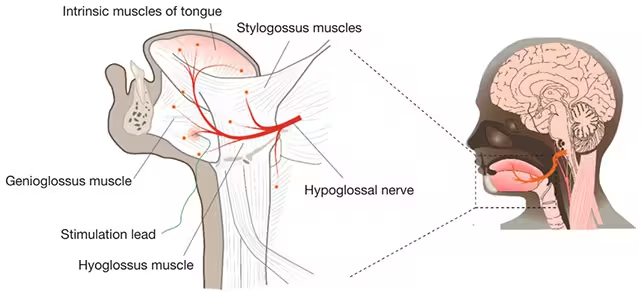

Hypoglossal nerve stimulation (HNS) isn’t new. The approach electrically activates the hypoglossal nerve, the motor nerve that controls tongue movement, so the tongue won’t fall back and block the throat during sleep. Existing HNS systems use a surgical implant and a more complex device. They help many patients but are invasive, require an operating room and, crucially, don’t suit everyone.

The team set out to test a smaller, easier-to-insert electrode that could be placed in a clinic rather than a hospital. In brief stimulation trials—lasting only a few breaths—the new electrode opened the airway in 13 of 14 participants, a 93 percent success rate. In some experiments it even restored airflow when breathing had stopped entirely. Those are sharp early results for a technique that takes about 90 minutes under ultrasound guidance and, according to the authors, causes minimal discomfort.

The treatment focuses on the hypoglossal nerve, pictured here in red.

Clinical context and why this matters

Continuous positive airway pressure, or CPAP, remains the standard first-line treatment for OSA: a mask delivers constant air pressure to keep the airway open. CPAP works remarkably well when used, but adherence is a major obstacle—roughly half of patients cannot tolerate it long term. That gap is where HNS has found a role: as an alternative for those who can’t wear CPAP but still need an effective intervention.

What makes the miniature electrode promising is not only its effectiveness in this small study, but its potential to broaden access. Less invasive procedures generally mean fewer complications, shorter recovery, and lower costs. They can also be adjusted with greater precision after implantation, tailoring stimulation to an individual’s anatomy and breathing patterns. As Amal Osman, the study’s lead author and a physiologist at Flinders University, puts it, the method may reduce recovery time and costs while improving success rates for people who cannot tolerate conventional treatments.

Still, caution is necessary. The tests took place in a controlled sleep-lab environment with a small number of participants. Laboratory settings are useful for demonstrating proof of concept. They do not replace larger, longer-term clinical trials needed to measure sustained effectiveness, device reliability, and real-world tolerability over months and years.

Implications and future directions

There are several practical benefits to developing a less invasive HNS. First, candidates previously judged unsuitable for traditional HNS might become eligible. Second, treating patients in a clinic shortens waiting lists and could change how sleep services are organized. Third, miniaturized electrodes can potentially be combined with wearable sensors or smart sleep systems for responsive, personalized therapy.

The Flinders team also suggests the possibility of targeting other nerves or muscles involved in airway patency, expanding therapeutic options. Integration with wearable technology could allow stimulation to activate only when needed, conserving battery life and enhancing comfort. Before any of that, though, the approach must be tested in larger cohorts and in patients’ home environments.

Expert Insight

‘This is the kind of incremental innovation that can transform care,’ says Dr. Lena Morales, a sleep medicine specialist and researcher not involved with the study. ‘Smaller implants reduce barriers—both physical and psychological—for patients. But we need multi-center trials to confirm long-term outcomes and to understand which subgroups benefit most.’

Flinders clinicians emphasize the next steps: refine the electrode design, validate safety over time, and study real-world effectiveness outside the lab. If those stages succeed, HNS could move from a niche surgical option to a widely accessible, clinic-based treatment that gives millions of people another chance at uninterrupted sleep.

Researchers hope the device can one day be combined with smart monitoring and less invasive delivery methods to make treatment faster and more personalized. For people exhausted by broken sleep, that future can’t come soon enough.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

labcore

Wow didn't expect that, a tiny electrode nudging the tongue and opening airways? If real, could change lives. Lab results look promising but need long term data, pls

Leave a Comment