5 Minutes

You can carry a normal weight and still be hiding a risk. Is body mass index telling the full story about cognitive health? A new analysis of MRI scans suggests the simple number on a scale misses where fat collects — and that location might matter for the brain.

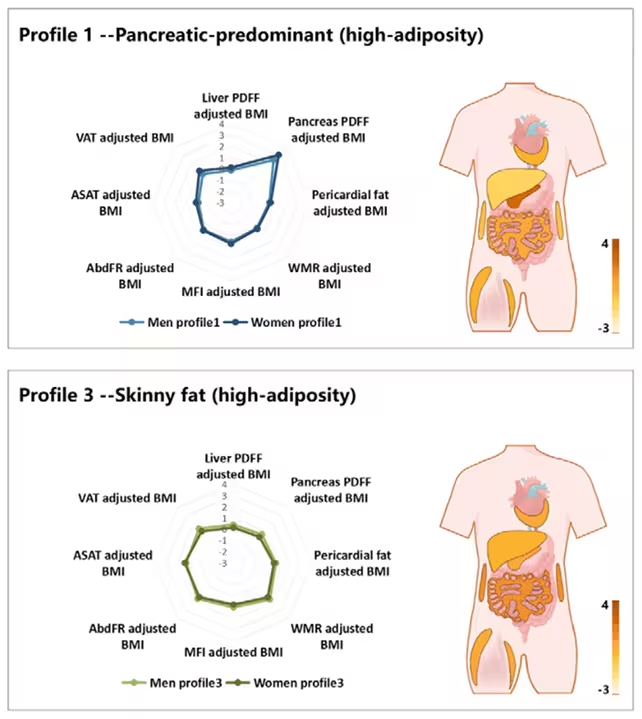

Researchers in China examined nearly 26,000 people from a UK imaging database, average age 55, and used a statistical method called latent profile analysis to group participants by how fat was distributed across the body. Instead of labeling everyone by BMI alone, the team let the MRI data—measuring fat around organs and in different compartments—define patterns. The result: six distinct fat-distribution types, two of which were surprising and previously unrecognized.

Unpacking the risky profiles

One profile the team identified had unusually high fat around the pancreas, which they labeled "pancreatic-predominant." Another looked like what clinicians sometimes call "skinny-fat": people who appear lean by BMI but still harbor concentrated pockets of fat around organs. Both profiles correlated with worse brain imaging markers—smaller brain volume, less gray matter and more white matter lesions—alongside poorer performance on cognitive tests.

These associations carried additional signals: the pancreatic-predominant and skinny-fat patterns were linked to accelerated brain aging and a higher likelihood of neurological diagnoses, a broad category that includes conditions as varied as anxiety disorders, multiple sclerosis, stroke and epilepsy. The study also found sex-dependent differences. Accelerated brain-age markers showed up more clearly in men, while the pancreatic-predominant pattern correlated more strongly with epilepsy risk in women.

"MRI gives us a precise map of where fat sits inside the body, not just how much of it there is," the study's radiologist Kai Liu explained to colleagues. The data-driven classification revealed distribution types that standard measures would have missed, he added, and those types appear to carry independent risk for neurodegeneration.

Why might internal fat affect the brain? Visceral and ectopic fat—fat stored inside the abdomen and around organs—are metabolically active. They release inflammatory molecules and hormones that can alter blood vessels, insulin signaling and immune activity. Over years, those processes can influence the brain's structure and function, contributing to gray matter shrinkage and white matter damage.

Context, limits and what comes next

The study reinforces a growing view in medical science: BMI is blunt. Two people with identical BMIs can have very different internal landscapes. One may have mainly subcutaneous fat beneath the skin; another may have excess visceral fat hugging the pancreas, liver or heart. Those internal patterns may change long-term risk in ways BMI cannot capture.

Still, there are important caveats. The research is cross-sectional—a snapshot in time—so it cannot prove fat distribution causes brain decline. Participants skewed middle-aged and were all sampled in the UK, which limits generalizability. Longitudinal studies across diverse populations will be necessary to confirm causality and to track whether changes in fat distribution predict later cognitive decline.

If future work validates these profiles, the clinical implications could be meaningful. Routine imaging or targeted metabolic tests might identify at-risk individuals earlier, allowing lifestyle interventions or tailored medical therapy before substantial brain changes occur. Think of it as moving beyond weight to a map of risk.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Márquez, a neuroendocrinologist not involved with the study, says the findings align with what endocrinology has been revealing for years: "Fat is not inert. Its location determines the signals it sends. Visceral fat behaves like an endocrine organ—churning out cytokines and hormones that can affect blood-brain barrier integrity and neural health. Detecting those patterns early could change how we prevent cognitive decline."

The research, published in Radiology, encourages a reframing: brain health is partly a story of distribution, not just accumulation. Ask not only how much fat you carry, but where it chooses to settle—and whether medicine is ready to read that map and act upon it.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

bioNix

wow didn't expect that, the idea of skinny-fat brain risk is kinda scary. MRI maps over BMI, huh? makes me rethink diet, sleep stress.. messy but important

Leave a Comment