5 Minutes

Imagine a waiting room where blood type no longer decides who gets a kidney. Fast. That’s the promise behind a recent laboratory milestone: researchers have turned a type A kidney into what they call an enzyme-converted type O organ — in effect, a kidney stripped of the sugar markers that make it recognizable as type A. The goal is simple and enormous: broaden compatibility so more patients can get transplants sooner.

How the conversion works and what scientists tested

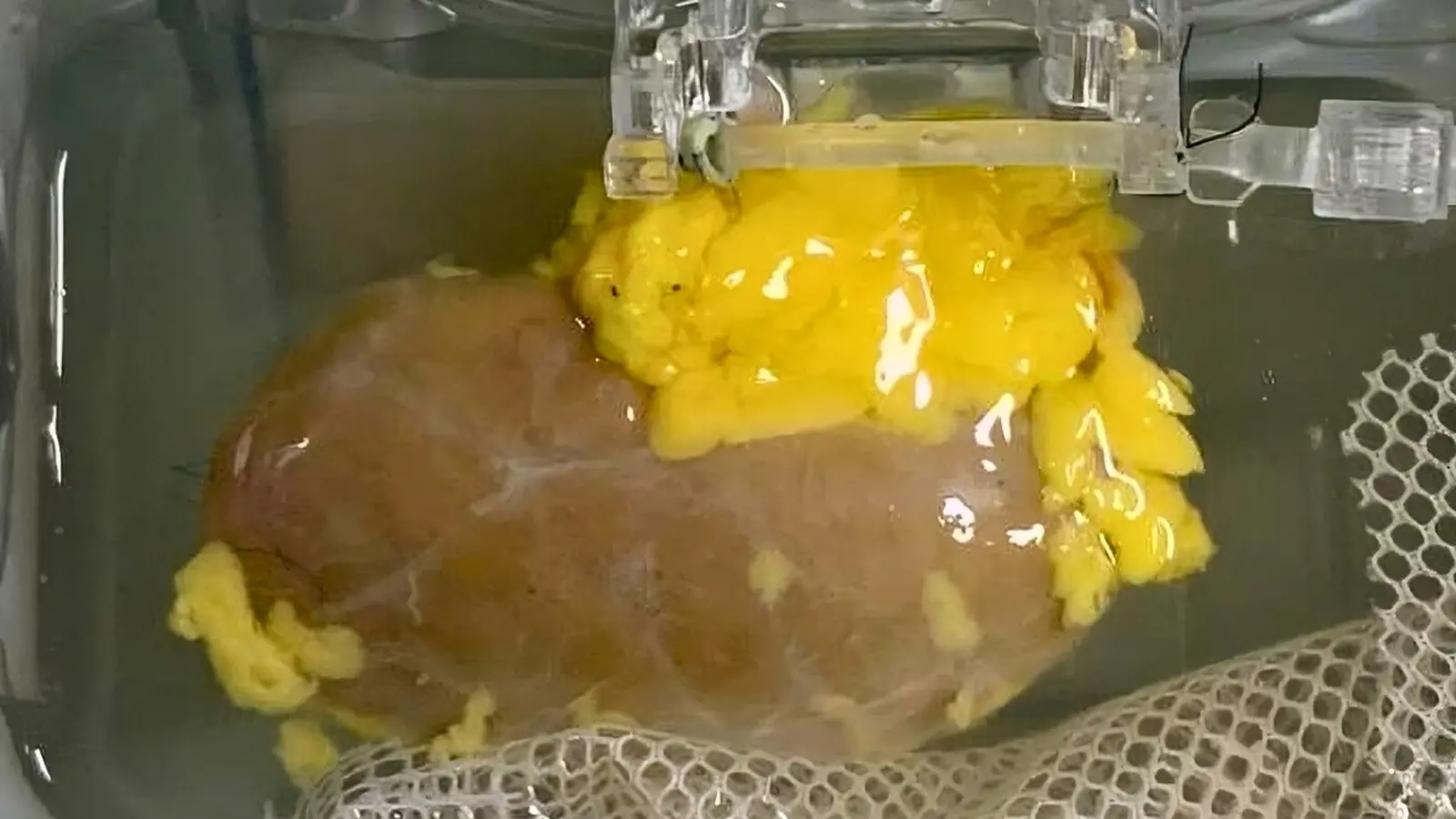

Blood groups hinge on tiny sugar molecules, known as antigens, that decorate the surface of cells and tissues. The immune system uses antibodies to read those molecular name tags. If it encounters a tag it recognizes as foreign, rejection can follow. The team used enzymes — molecular scissors engineered to cut specific sugar residues — to shave off the antigenic parts of the type A chains. Once those sugars are removed, the organ’s surface becomes effectively ABO-antigen-free, resembling a type O profile.

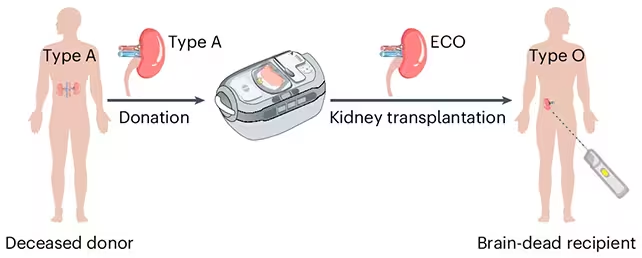

This isn’t theoretical tinkering. A collaborative group from Canada and China prepared an enzyme-converted type O (ECO) kidney and transplanted it into the body of a brain-dead donor who had been authorized for research. The organ functioned for several days. It wasn’t perfect. By day three, traces of the original type A markers began to reappear and an immune response emerged. Still, the reaction was milder than expected, suggesting the approach nudges the immune system toward tolerance rather than provoking full-scale rejection.

The researchers produced an enzyme-converted type O (ECO) kidney ready for transplant.

Why this matters and the road ahead

Type O patients face the longest waits because O kidneys are in demand by everyone: O is the universal donor type for red blood cells and, in practice, O kidneys are compatible with other blood types. That imbalance is deadly. In the United States alone, roughly 11 people die each day waiting for a kidney transplant. Many are on hold for type O organs.

Current workarounds exist. Doctors can desensitize a recipient or perform careful antibody removal before transplant, but those protocols are complex, costly and risky — and they typically require a living donor and time to prepare the recipient. An enzyme-based conversion of donor kidneys could change the calculus by expanding the pool of usable deceased-donor organs without lengthy preconditioning.

Several scientific and clinical challenges remain. The antigen re-expression after a few days suggests either incomplete removal, surface turnover of glycoproteins, or immune-driven regeneration of the sugars. Long-term durability of conversion, potential side effects of the enzymes, and the risk of unintended tissue changes all require systematic study. Regulatory hurdles and larger-scale human trials lie ahead before hospitals can adopt this technique.

.avif)

This research also sits alongside other strategies aimed at relieving organ scarcity: xenotransplantation using pig kidneys, engineered antibodies to blunt rejection, and improved immunosuppression regimens. Together, they form a multi-pronged assault on a single problem — too many patients, too few organs.

“This is a rare moment when decades of molecular glycobiology intersect with bedside need,” one investigator observed, describing how basic enzyme chemistry is finally being tested in a human model. The results are early, but they point toward a future where compatibility is engineered rather than waited for.

If enzyme conversion can be made durable and safe at scale, the effect on waiting lists could be dramatic: more usable kidneys, shorter waits, and fewer preventable deaths. The work is a reminder that solutions to clinical crises often come from small, precise edits at the molecular level — a snip here, a saved life there.

For patients and clinicians alike, the next few years will be crucial: larger trials, thorough safety assessments, and careful monitoring to see whether this molecular trick can translate into lasting clinical benefit.

Until then, the experiment stands as a hopeful proof-of-concept — one enzyme cut at a time.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

labcore

wow, didn't expect this! enzyme-cut kidneys sound like sci-fi finally in clinic. Reappearance by day 3 though... worrying. If they fix durability this could save so many lives, but i'm cautious.

Leave a Comment