6 Minutes

After more than a decade of laboratory work, researchers report a major advance toward making kidneys that could be accepted by recipients of any blood type. A multinational team has converted donor kidneys into an antigen‑free form that—at least temporarily—behaved like a type O organ when transplanted into a human model, a step that could help reduce long transplant wait lists and save lives.

The kidney being prepared in the lab

Turning blood‑type barriers into a technical problem

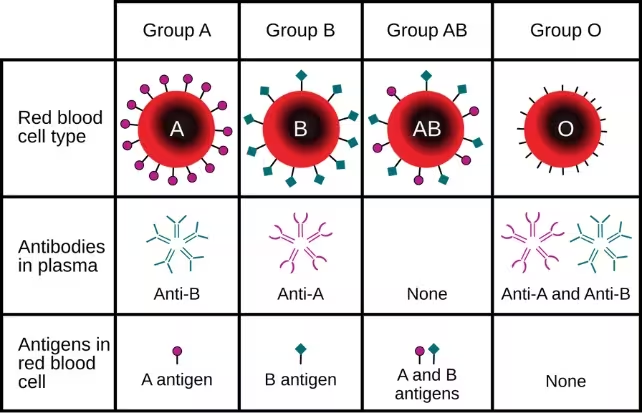

Blood type compatibility is one of the largest practical obstacles in kidney transplantation. The ABO blood group system places a hard constraint on who can receive which donor organ: type O recipients usually must wait for a type O donor, and type O kidneys are in especially high demand because they can work in recipients of other blood groups.

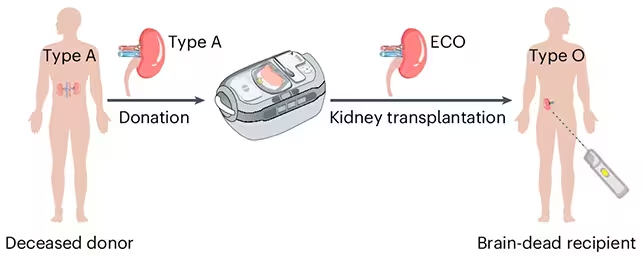

To sidestep that constraint, scientists adapted enzymes that selectively remove the sugar molecules—called antigens—on the surface of blood cells and donor tissues that tell the immune system "this is foreign." The research team used those enzymes to strip away the markers of type A blood on a donated kidney, effectively converting it into an enzyme‑converted type‑O (ECO) organ.

The researchers produced an enzyme-converted type-O (ECO) kidney ready for transplant. (Zeng et al., Nat. Biomed. Eng., 2025)

Biochemist Stephen Withers of the University of British Columbia, who is quoted in the original report, describes the enzymes like a pair of molecular scissors: they cut off the antigenic sugars that define type A, uncovering the neutral chemistry equivalent of a type O surface. "Once that's done, the immune system no longer sees the organ as foreign," he says, noting that this is the first time the method has been tested in a human model.

What the experimental transplant showed—and what it didn't

The converted kidney was implanted into a brain‑dead donor who had given consent via their family for research use; the organ functioned for several days inside that recipient. That period of function gave scientists important real‑world data about how the immune system responds when an organ's ABO markers have been chemically removed.

However, the conversion was not permanent. By the third day after transplantation, the type A markers began to reappear on the kidney's tissues, provoking an immune response. Critically, the reaction was less severe than would normally be expected for a mismatched transplant, and there were signs that the host's biology was moving toward tolerance rather than outright rejection. Still, re‑expression highlights a central challenge: how to make antigen removal durable enough for routine use in living recipients.

Context: why this could reshape kidney transplant logistics

Kidney shortages are stark. In the United States alone, roughly 11 people die every day waiting for a kidney transplant, and many of those deaths are among people who need type O organs. Current clinical strategies to overcome blood‑type incompatibility—so‑called desensitization protocols—can work but are time‑consuming, risky, and expensive. Those protocols also usually require the recipient to be known in advance, which limits their applicability with deceased donors.

A reliable method to convert donor kidneys into a universal form could dramatically increase the pool of usable organs, shorten wait times, and reduce mortality on transplant lists. It could also simplify logistics: instead of matching ABO types or performing long desensitization regimens, clinicians might be able to treat an organ ex vivo (outside the body) and move ahead with transplantation more quickly.

Scientific hurdles and next steps

Several technical and clinical issues remain before this approach can be offered to living patients. Key questions include how to prevent antigens from reappearing, how to scale enzyme treatments for many organs, and how to ensure the conversion doesn't introduce other vulnerabilities—such as increased susceptibility to infection or harmful immune activation.

Researchers are considering complementary strategies: pairing antigen removal with targeted immunomodulation, improving enzyme potency and retention, or combining conversion with other innovations like engineered antibodies or xenotransplantation (pig kidneys). Longitudinal studies in animal models and additional human‑model work will be necessary to map out safety and durability.

Expert Insight

"This is a measured but exciting advance," says Dr. Maya Patel, a transplantation immunologist not involved in the study. "Demonstrating short‑term function in a human model is a major milestone. The next task is engineering persistence—making sure the antigen profile doesn't creep back days or weeks later. If scientists can lock the conversion in place or pair it with selective immune tuning, the impact on wait lists could be enormous."

Scientists are also watching parallel avenues: improved matching algorithms, broader use of living donors, and genetically modified animal organs. Taken together, these efforts reflect a multi‑pronged assault on a global problem—organ scarcity.

What this means for patients and the healthcare system

For patients, a safe, reliable universal kidney would mean fewer months or years on dialysis and lower mortality while waiting. For health systems, it could reduce the intense costs associated with prolonged dialysis and complex desensitization procedures. For researchers, it presents a clear engineering and immunology problem: how to make a molecular fix last long enough to change clinical practice.

The study appears in Nature Biomedical Engineering and represents a tangible example of basic biochemistry translating toward patient care. As Withers observed about the team's progress, seeing laboratory insights edge closer to clinical reality is exactly what motivates this long‑term work.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

skyspin

Promising but feels a bit overhyped. Short term function in a brain dead model ok, but antigens came back by day 3. If they...

enzLab

Wow this could change lives... but day 3 reappearance worries me. Can they lock it in? Hope so, but skeptical.

Leave a Comment