3 Minutes

They were tiny, fragile, and swept up in something much larger than themselves. A fresh look at a Late Jurassic fossil bed reveals dozens of baby pterosaurs preserved together—an image that reads like a snapshot of a single, violent event rather than the slow grind of normal mortality. Bones lie articulated, juveniles clustered, sediments showing the stamp of a sudden surge. Paleontologists are calling it a classic storm burial, and it rewrites how we picture life and death in the skies 150 million years ago.

Why a storm answer matters

At first glance, a mass of small skeletons can mean many things: parental care gone awry, a colony collapse, or even predators at work. But sediment patterns and the absence of widespread bite marks point toward a short, catastrophic event—a powerful storm surge that trapped and buried the hatchlings where they nested or roosted. Think of a coastal flash flood today, but on the Jurassic shoreline, with wind and water sweeping animals into a single deposit that fossilized in remarkable detail.

That detail is valuable. For decades, scientists have debated how pterosaurs raised their young, how often juveniles survived to adulthood, and how predators fit into those ecosystems. This new taphonomic picture—taphonomy being the study of how organisms decay and become fossilized—lets researchers separate routine mortality from episodic catastrophe. When death is sudden and widespread, the signal about behavior and environment is much clearer.

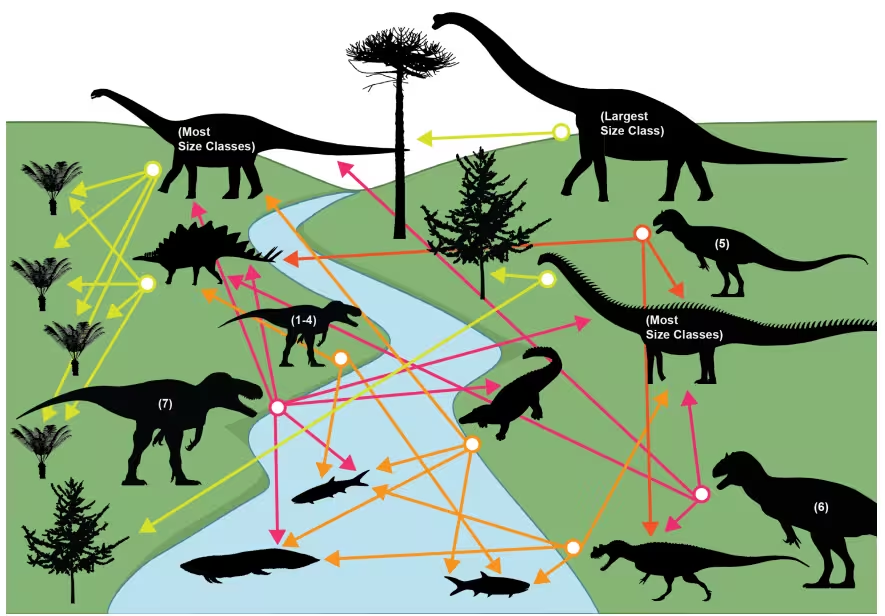

It also shifts perspective on the predators that shared those landscapes. William Hart, a paleontologist at Hofstra University, notes that apex theropods of the Late Jurassic, such as Allosaurus and Torvosaurus, likely operated in an environment where prey and carrion could be comparatively abundant. In plain terms: these Jurassic hunters and scavengers may have found food more easily than the iconic Tyrannosaurus rex did tens of millions of years later, when food chains had reorganized and opportunities were different.

Why does that comparison matter? Because predator behavior and ecosystem structure are linked. If juvenile pterosaurs were occasionally concentrated by storms, they became temporary resources—easy meals for opportunistic carnivores. Yet when the fossil bed shows minimal scavenging, it suggests the burial happened fast enough to deny predators access. That tension between abundance and accessibility is what ecologists call a changing resource landscape, and it helps explain how different eras favored different hunting strategies.

Beyond feeding dynamics, the find informs life-history questions: Were pterosaurs nidicolous (staying in nests) or more precocial (able to move soon after hatching)? The clustering and developmental stages seen in the fossils tilt toward a scenario where young stayed put long enough to be caught by the storm—useful evidence for models of growth and parental investment in flying reptiles.

Storms can erase the ordinary and immortalize the extraordinary. In this case, they left behind a time capsule that clarifies behavior, ecology, and the fragile interplay between weather and life in the deep past. For paleontologists, it's a reminder that sometimes the key to a long-standing mystery is written in the mud.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment