3 Minutes

Imagine a scenario where a speeding rock a few hundred meters wide threatens a city. Would Hollywood's drill-and-detonate fantasy stand up to physics? Probably not. The more realistic — and far less cinematic — option favoured by some scientists is a standoff nuclear detonation: set off an explosion near the asteroid to vaporize a sliver of its surface and nudge its orbit. Simple in concept. Complicated in execution.

Study details and why composition matters

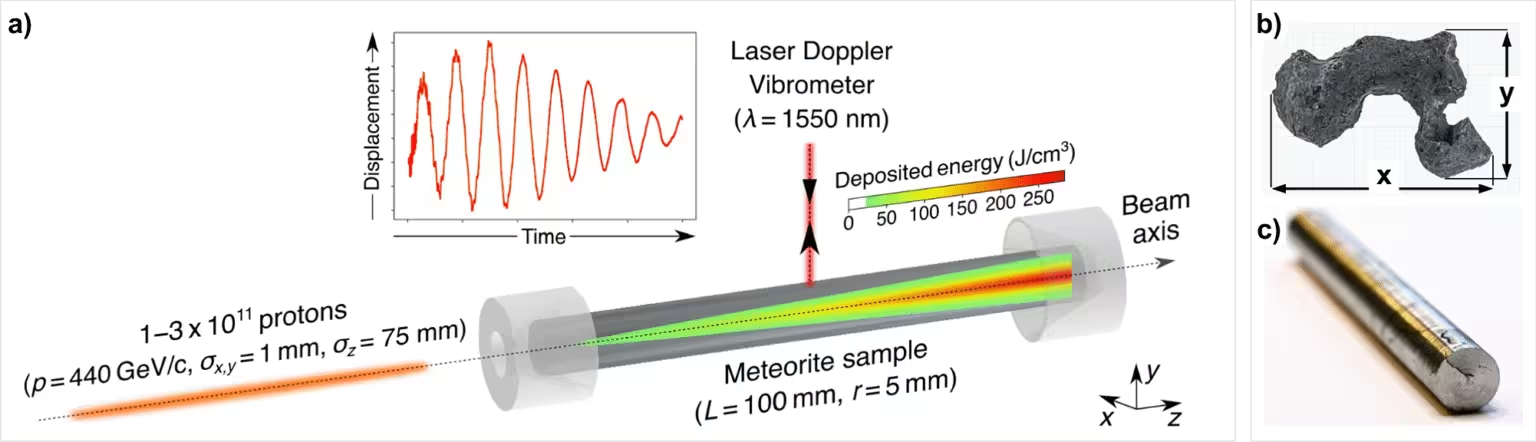

A recent paper in Nature Communications examined how an iron-rich, relatively homogeneous sample responds to the intense stresses from such an energetic impulse. Researchers picked an iron-dominant analogue because its internal structure is easier to model. Rocks that are mixtures of metal, rock, voids and loosely bound boulders will behave very differently: stress waves travel, reflect and dissipate according to how materials are arranged inside the body. In short, not all asteroids are created equal.

'The world must be able to execute a nuclear deflection mission with high confidence, yet cannot conduct a real-world test in advance. This places extraordinary demands on material and physics data,' says Karl-Georg Schlesinger, co-founder of OuSoCo and co-leader of the research team. That tension — between unavoidable uncertainty and the need for reliable answers — shapes the whole problem.

What the team showed is not a blueprint for a mission but a constraint map: how energy injected near the surface translates into momentum change depends strongly on internal cohesion, porosity and the spatial mix of materials. A monolithic iron core will transmit shock and move differently from a 'rubble pile' made of loosely aggregated rocks. Engineers planning any mitigation architecture must therefore fold composition into trajectory models, not treat the asteroid as a uniform object.

There are practical implications. Remote-sensing campaigns must prioritize accurate compositional and structural characterization long before any intercept. Laboratory experiments and high-fidelity simulations need to expand beyond neat, single-material tests to include mixed, fractured, and porous analogues. And planetary defense policy must accept that unverifiable tests will keep some uncertainty on the table.

Theoretical work like this gives mission designers the physics-based confidence they desperately need. If humans ever must deflect a threat, the success of that action will hinge less on spectacle and more on careful materials science, precise reconnaissance, and the ability to model messy, inhomogeneous worlds.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment