5 Minutes

A small, daily tablet can save a life — and sometimes it can also cause muscles to burn, cramp or fail. For roughly one in ten people who take statins to lower LDL cholesterol, unexplained aches and profound fatigue become a real reason to stop treatment.

Researchers at Columbia University and the University of Rochester have traced many of those symptoms to a single molecular misstep: certain statins appear to pry open a calcium channel in skeletal muscle cells. Once that gate stays ajar, calcium floods the fibers, enzymes activate, and a cascade of damage can follow — from chronic soreness and weakness to rare but catastrophic syndromes such as rhabdomyolysis.

How a cholesterol drug collides with a muscle gate

Statins do their good work in the liver. They block HMG-CoA reductase, an enzyme essential for synthesizing cholesterol, and in doing so they reduce levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), a major driver of atherosclerosis and heart attacks. But biology is messy. Molecules designed for one protein can nudge others.

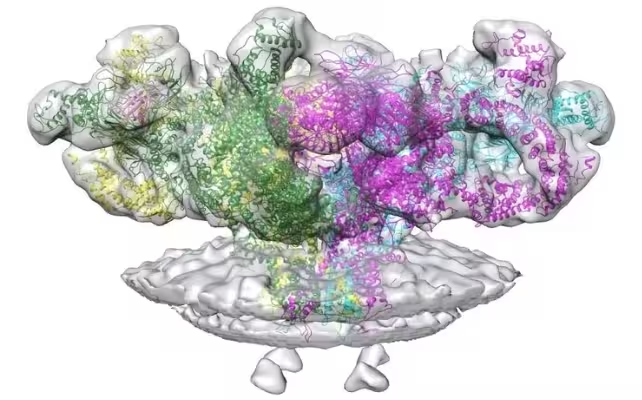

Enter RyR1 — ryanodine receptor 1 — a mushroom-shaped calcium channel embedded in the sarcoplasmic reticulum around muscle fibers. Think of RyR1 as the bouncer at a crowded club: it controls when calcium can surge into the dance floor and set muscle fibers contracting. Too little, and movement fails. Too much, and the tissue self-destructs.

Structure of RyR1, a protein channel that allows calcium to leak into muscles.

Using cryo-electron microscopy on mouse tissue, the team captured statin molecules perched on RyR1 and altering its shape. Cryo-EM freezes samples and maps electron scatter to reveal near-atomic structures; here it showed how simvastatin and similar compounds can stabilize an open state of the channel, permitting calcium to leak continuously into muscle cells.

Leakage alone explains many common complaints: persistent muscle pain, tenderness, cramps, and a lingering sense of weakness. But in people with certain RyR1 genetic variants, the risks increase. Those individuals already have channels prone to excessive opening and can develop malignant hyperthermia when exposed to triggering drugs, or face diaphragm weakness that undermines breathing.

There are rarer, grimmer outcomes. Rhabdomyolysis, in which muscle fibers rupture and release toxic contents into the bloodstream, can follow severe RyR1-mediated damage and lead to kidney failure. Autoimmune necrotizing myositis — an immune attack that kills muscle cells — can also occur with statin exposure, although that mechanism appears distinct from direct RyR1 leakage.

Implications, treatments and next steps

The discovery does not explain every case of statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS). But it provides a concrete pathway to test and to fix. For clinicians, the finding suggests that genetic screening for RyR1 variants and a more nuanced evaluation of muscle complaints could help distinguish true statin intolerance from unrelated pain.

Two therapeutic routes look promising. One is medicinal chemistry: redesign statins so they retain liver-targeted inhibition of cholesterol synthesis but shed affinity for RyR1. The other is pharmacological rescue of the channel. In mice made intolerant to simvastatin, an experimental drug class called Rycals restored closed-channel behavior and prevented muscle weakness.

"I've had patients who've been prescribed statins, and they refused to take them because of the side effects," says Andrew Marks, the Columbia cardiologist who led the study. "It's the most common reason patients quit statins, and it's a very real problem that needs a solution."

Public-health stakes are high. About 40 million adults in the United States take statins. If even a fraction suffer clinically meaningful SAMS, opportunities to prevent heart attacks are being lost, while patients endure avoidable pain and disability.

Expert Insight

"This work gives us a testable target," says Dr. Elena Morales, a muscle physiologist at a major medical center who was not involved in the study. "From a translational point of view we can screen drugs for RyR1 binding early, and clinicians can think about RyR1 function when statin myopathy appears. It's a bridge from structural chemistry to bedside decisions."

The research reshapes a long-standing mystery into a tangible mechanism. It opens avenues for safer cholesterol therapies and for targeted treatments that could keep statin benefits within reach for patients who need them most.

Which path will clinicians and drug developers take next? Time — and careful trials — will tell.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

coinpilot

Is this real or just lab mice drama? Curious if simvastatin in humans shows same RyR1 binding. Need human trials, not just cryo pics, hmm

labcore

Wow, who knew a tiny pill could open muscle calcium gates? kinda scary... my grandma stopped statins years ago, maybe this explains it. ugh

Leave a Comment