4 Minutes

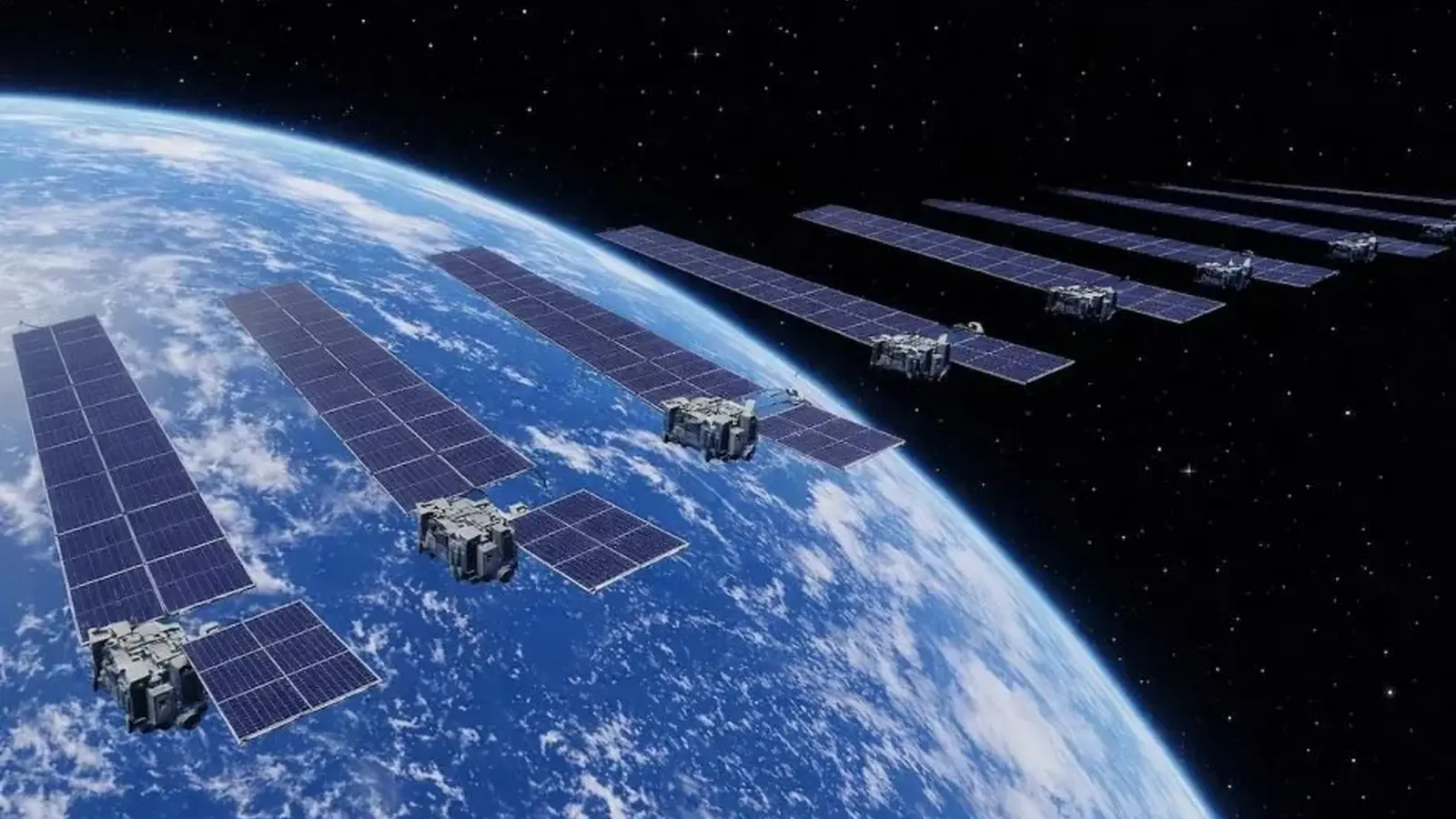

Imagine a server farm that never touches soil, humming above the atmosphere and cooled by the vacuum of space. That image is no longer pure science fiction. SpaceX has filed for permission with the U.S. Federal Communications Commission to deploy an enormous constellation of orbital data centers — a plan that, on paper, stretches to as many as one million satellites.

The company frames the idea as a radical answer to a growing problem: terrestrial data centers now power the boom in artificial intelligence and cloud services, but they consume massive electricity, rely on huge amounts of water for cooling, and can spark fierce local opposition when operators try to expand. Space-based servers promise a different set of trade-offs. Sunlight is abundant in low Earth orbit, waste heat can be shed by radiation into space, and laser-based links could stitch a network of distributed processors that do not depend on local power grids.

Technical concept and ambitions

SpaceX envisions small, solar-powered modules in low Earth orbit (LEO) that communicate via laser inter-satellite links. Batteries would buffer short periods without direct sunlight, while optical beams would route data across the swarm. In the company filing, the project is described with grand language — even invoking the concept of a Kardashev type II civilization as a metaphor for harnessing stellar energy at scale — but the immediate claim is practical: lower carbon footprints and cheaper long-term operations compared with sprawling ground-based server farms.

Is that realistic? Parts are. Solar arrays work. Laser links exist and are improving rapidly. Radiative cooling in vacuum is a genuine advantage over water-intensive terrestrial cooling. But scaling those building blocks to a coastal-size constellation introduces new engineering and economic questions: launch cadence, on-orbit maintenance, radiation hardening of electronics, and secure, low-latency connections to users on the ground.

Risks in orbit and regulatory friction

Any blueprint that proposes multiplying the number of human-made objects in LEO by orders of magnitude sets off alarm bells. Orbital congestion is not an abstract hazard; collisions produce debris that endangers other satellites and can create cascading chain reactions. European space agencies and analysts already count many thousands of active satellites, and a single program adding even a fraction of a million new platforms would dramatically alter traffic patterns and collision risk. SpaceX, for its part, argues that the environmental and economic payoffs justify the approach and that responsible design, collision-avoidance systems, and end-of-life disposal plans can mitigate hazards.

Regulators are likely to push back. The FCC review process is where those debates begin — and it is common for companies to file ambitious proposals that become bargaining chips in longer negotiations. Even if regulators never approve anywhere near a million units, the application signals where industry interest is drifting: toward off-world solutions for problems created by the planet-bound internet economy.

The proposal raises bigger questions than engineering. Who owns orbital infrastructure that hosts someone else’s computing? How will ground-to-space latency limits shape which workloads can migrate to orbit? And perhaps most plainly: do the ecological gains from avoiding terrestrial power and water usage outweigh the new environmental and safety costs of a crowded orbital environment? The answers will depend as much on policy and international cooperation as on rockets and lasers.

Leave a Comment