5 Minutes

They will test time inside the eye. Short sentence. Bold ambition.

Life Biosciences, a Boston-based startup, has secured U.S. Food and Drug Administration clearance to begin the first human trial of a therapy designed to roll back cellular aging. The project, code-named ER-100, uses a controlled form of cellular reprogramming — an approach that seeks to restore old or damaged cells to a younger functional state by resetting their epigenetic switches. The immediate objective is narrow and concrete: treat glaucoma, a disease in which elevated eye pressure damages the optic nerve and can cause irreversible blindness.

How the therapy works and why the eye is first

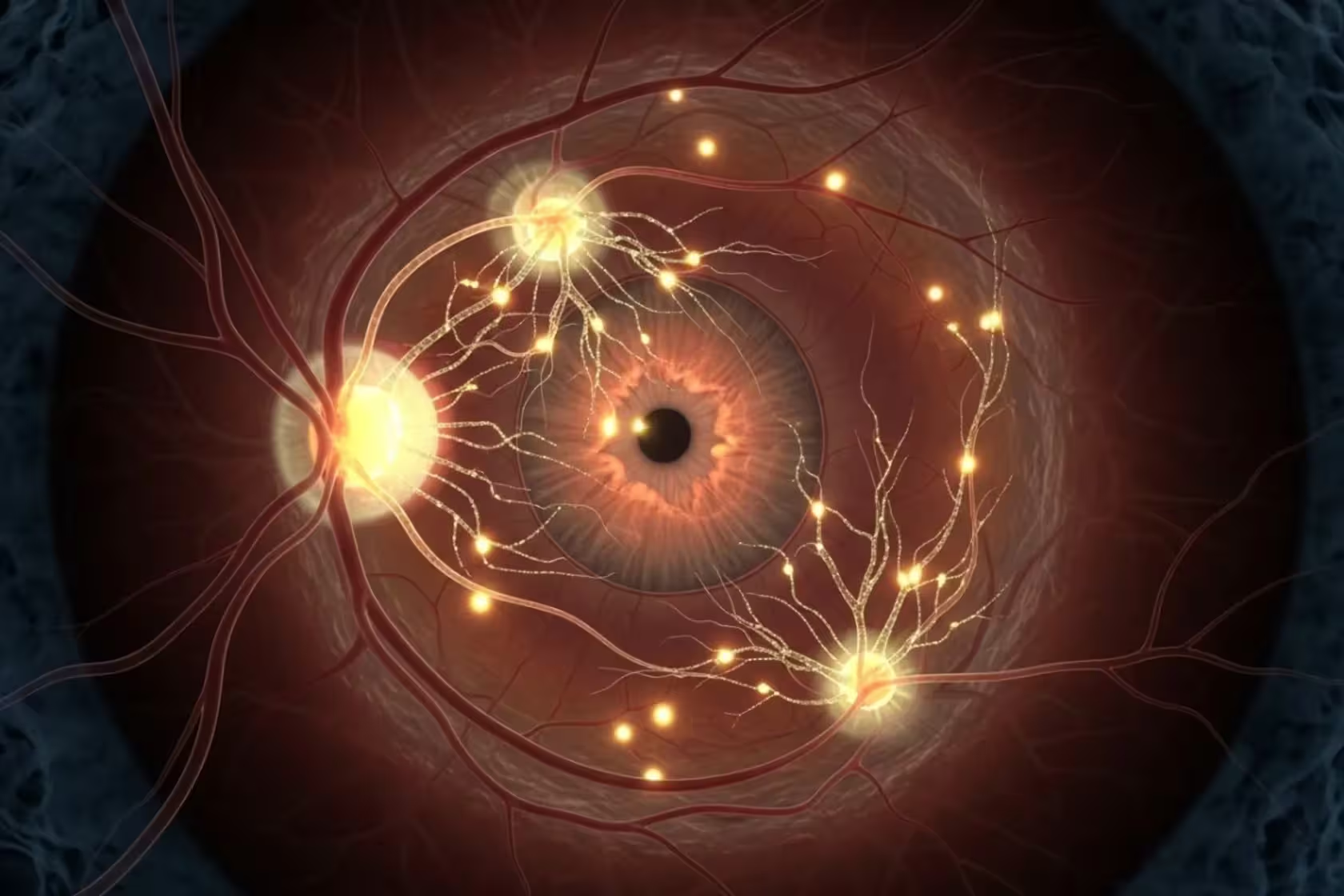

At the core of ER-100 is a molecular trick first hinted at by Nobel-winning research two decades ago: a handful of factors can coax mature cells back toward an embryonic-like, more plastic state. Life Biosciences applies a partial, temporary version of that method so cells don’t lose their identity. Instead, they become younger and more capable within the tissue where they already belong.

Technically, the company will deliver three regenerative genes into retinal tissue using viral vectors. The genes remain off until patients take a prescribed dose of the antibiotic doxycycline, which acts as a safety switch to trigger gene expression. That inducible system is meant to reduce risks such as uncontrolled cell growth or oncogenesis. Why the eye? Because it is relatively self-contained. The globe of the eye provides a localized, immune-privileged environment, limiting systemic exposure and making early human testing safer than starting with a whole-organ approach.

Trial design, safety questions and prior results

The initial cohort will include roughly a dozen patients with advanced glaucoma. Researchers will monitor visual function, nerve health, and signs of local or systemic immune activation. Safety is central. Viral delivery and the use of gene-control elements derived from bacteria and bacteriophages raise valid concerns: immune reactions, inflammation, or unintended genomic effects are all on the list of risks to watch for.

There is precedent in animals. In 2020, David Sinclair, a co-founder of Life Biosciences and a professor at Harvard, reported restoration of vision in mice using a similar reprogramming strategy — a result that sparked excitement and scrutiny in equal measure. The effort drew fresh attention after comments by public figures at the Davos forum; among them, Elon Musk described the idea of reversing aging as “very achievable,” a phrase that helped push media and investor focus toward the company and the broader field of cellular reprogramming.

If ER-100 proves safe and shows signs of restored nerve function in the eye, the implications extend well beyond glaucoma. Scientists and investors already imagine a future in which cellular rejuvenation could be applied to other tissues — perhaps even entire organs. That day is not guaranteed. But success in a controlled organ like the eye would mark a decisive step toward wider human applications.

Ethical and regulatory landscape

Regulatory oversight will be rigorous. Institutional review boards and the FDA will require detailed safety monitoring and transparent reporting. Ethicists point out that therapies aimed at reversing biological age carry societal questions: who gets access, how to measure meaningful benefit, and what long-term follow-up is required to detect late-arising effects. Researchers emphasize caution. Early-phase trials are built to test safety first, not to promise a fountain of youth.

Expert Insight

“This is a natural next step for a technology that has matured in the lab,” says Dr. Laura Keane, a regenerative-medicine clinician and lecturer at a major research university. “Choosing the eye is conservative and smart. It lets scientists evaluate biological rejuvenation in a contained system where functional outcomes — like vision — are measurable and immediate.” Her voice is steady. She adds, “We must watch for immune events and off-target activity, but a clean safety record here would be a watershed moment for translational aging research.”

There are still many unknowns. Timelines will depend on how patients respond and whether independent researchers can reproduce results. But one reality is already clear: cellular reprogramming has moved from theory and mice to human testing, and with that shift comes a flurry of scientific, ethical, and commercial questions that will shape the future of medicine and aging research.

Comments

nodegrid

Ambitious move. feels overhyped but choosing the eye is smart. If safety checks out, this could open doors, but still a long road... skeptical, excited

labFlux

wait, they test time inside the eye? sounds wild and thrilling, but viral gene delivery, doxy as a switch, is that really safe long term tho...

Leave a Comment