6 Minutes

Girls who reach their teens without an autism diagnosis are not necessarily unaffected — they are often simply unseen. The phrase that stuck with clinicians and families after a new Swedish analysis went public is blunt and unsettling: by adulthood, the sex gap in clinical autism diagnosis all but disappears.

What the study measured and why it matters

Researchers led by Caroline Fyfe at the Karolinska Institute examined the medical records of more than 2.7 million people born in Sweden between 1985 and 2020. That scale — national registers spanning decades — is rare in neurodevelopmental research and gives the team a way to track diagnosis patterns from childhood into early adulthood. It also provides fresh evidence that the commonly quoted four-to-one male-to-female autism ratio may be more an artifact of how and when we diagnose than a true difference in incidence.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent differences in social communication, tight or highly focused interests, repetitive behaviors, and a preference for routine. The DSM-5 frames these core features, but it does not capture the full variability in how people present across sexes, ages, cultures, or coexisting conditions such as ADHD, anxiety, or intellectual disability.

Diagnostic pathways usually begin in childhood, relying heavily on caregiver reports and the attention of teachers and pediatric clinicians. If a system expects autism to look one way — and that image is shaped mostly by studies of boys — then girls whose presentation differs can slip through the cracks. The Swedish study suggests that many such cases are later recognized, when symptoms or life demands change and lead people to seek assessment.

Findings and caveats from the Swedish registers

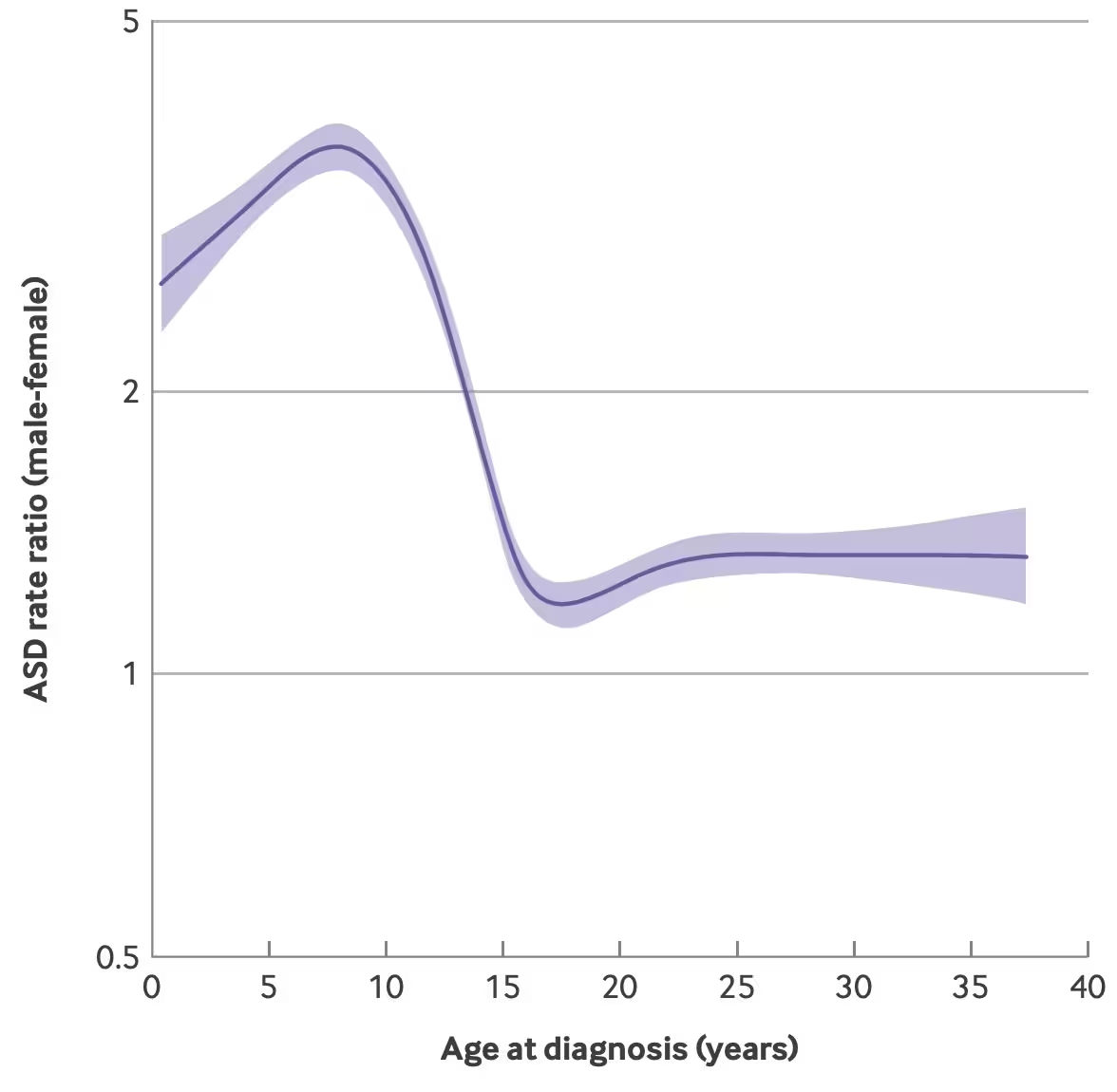

Fyfe and colleagues observed that, during childhood, boys were diagnosed with ASD at much higher rates than girls. However, those sex ratios steadily approached parity by around age 20. In other words, more women and girls were diagnosed later, shifting the balance over time.

There are multiple interpretations. One possibility is delayed emergence: traits that meet diagnostic thresholds might become more evident for some females only in adolescence or early adulthood. Another, and one that the authors and several advocates emphasize, is diagnostic bias — social, clinical, and institutional factors that make autism less likely to be recognized in girls early on.

Anne Cary, an autism patient and advocate who wrote an accompanying editorial, framed the problem plainly: expectation shapes detection. If parents and practitioners unconsciously expect boys to be autistic, they may overlook subtler or differently expressed signs in girls. Girls might also learn social masking techniques, consciously or unconsciously mimicking peers to avoid standing out. Both scenarios delay referral and diagnosis.

That said, the study has limitations the authors acknowledge. The sample is Swedish-born only, so patterns may differ where healthcare systems, cultural expectations, and diagnostic practices vary. The register lacked outpatient records before 2001; this may make earlier cohorts appear to receive diagnoses later than they actually did, potentially underestimating the true sex gap in some birth years. The analysis also did not fully account for co-occurring conditions that can alter diagnostic trajectories.

Age-specific male-to-female ASD rate ratios based on age at diagnosis.

Implications for diagnosis, treatment, and policy

If autism is under-recognized in girls during childhood, the consequences reach beyond labels. A late diagnosis can mean missed access to therapies, educational supports, and workplace accommodations at critical life stages. It can also affect mental health; untreated or unsupported autistic women and girls commonly report higher rates of anxiety and depression, often tied to the strain of masking or repeated misunderstandings.

Clinically, these findings argue for more nuanced screening tools and training that reflect sex-specific presentations. Schools and pediatric care networks need better guidance on when to refer for assessment, and adult services must be ready to evaluate older teenagers and young adults who present with longstanding but previously unrecognized developmental differences.

Expert Insight

"Large-scale register studies like this one are powerful because they reveal patterns we can't see in small clinic samples," says Dr. Maya Thompson, a clinical neurodevelopmental psychologist who has worked with adolescents and young adults seeking late diagnoses. "What I see in practice aligns with the Swedish data: many women arrive in their twenties asking why things were so hard in school or work, and only then do we piece together an autism diagnosis. That should change how we train clinicians and how we design screening in schools."

Dr. Thompson cautions against assuming all late diagnoses reflect prior oversight. "There's no single explanation. For some, challenges truly intensify later. For many others, systemic bias and masking are key drivers. Our response should be tiered: refine child screening, expand adult diagnostic access, and ensure supports follow the diagnosis, whenever it comes."

On the research front, the study's authors call for more work to parse phenotypic differences — how symptoms look across sexes — and to examine intersections with socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and co-occurring psychiatric or developmental conditions. International replications would also help determine whether the Swedish pattern holds in different healthcare contexts.

There’s a blunt policy message here: diagnosis is not just a medical label. It opens doors to services and accommodations that matter for education, employment, and wellbeing. If whole groups are being diagnosed later, then systems are failing to provide timely support.

Recognizing that the male-to-female diagnosis ratio shifts across the life course should prompt clinicians, educators, and policymakers to rethink screening age thresholds and diagnostic criteria. It should also encourage communities to listen to self-reported experiences of autistic women and girls, who often point to years of being misunderstood.

The Swedish registers don't give all the answers. But they do sharpen a question we need to answer together: If many autistic women are simply slower to reach a clinical label, how do we adapt systems so they don't have to wait to be seen?

Source: sciencealert

Comments

atomwave

wow that line about the sex gap fading by adulthood hit hard. how many girls masked for years, unseen and exhausted? makes me mad, sad.

Leave a Comment