8 Minutes

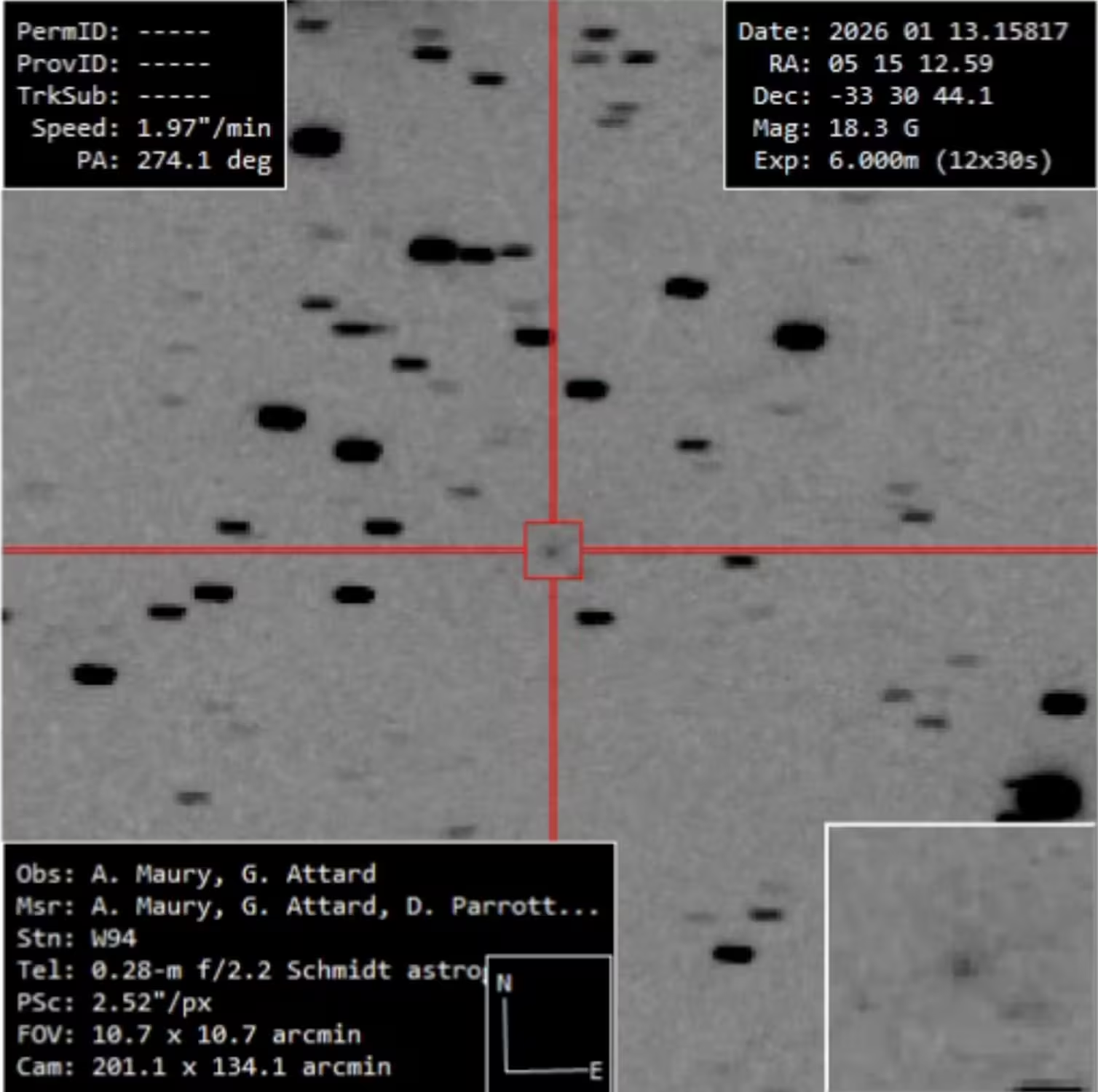

When a faint, icy smudge was logged from a remote telescope in the Atacama on 13 January, few expected it to carry the promise of a spectacle. The object, now catalogued as C/2026 A1 (MAPS), has the right pedigree to make skywatchers sit up: it belongs to the Kreutz family of sungrazing comets, a lineage responsible for some of history's most dazzling visitors.

Fragments of a lost giant

The Kreutz sungrazers are not a random cluster. They are the scattered remains of a monstrous parent that once brushed the Sun too closely, perhaps in the 3rd or 4th century BCE. Over centuries the original nucleus fractured, and its offspring have been returning along elongated, almost fatal orbits ever since. Some pieces are minute and vanish without fanfare. Others — rare and stubborn — survive the inferno near the Sun and become 'Great Comets'.

Two names anchor this family in modern memory: C/1965 S1 (Ikeya-Seki) and the Great Comet of 1882 (C/1882 R1). Ikeya-Seki, discovered a month before perihelion, soared to daytime visibility and rivaled the brightness of the full Moon. The 1882 visitor was even more radiant at its apex, a century-bright marvel that held the public's attention for months. Those events were not isolated flukes; they were the dramatic returns of fragments from that ancient, colossal nucleus.

Comet MAPS fits the pattern. At discovery it stood farther from the Sun than any sungrazer previously recorded at detection — a technical milestone that hints at one of two possibilities. Either MAPS is a relatively large fragment, bright enough to be detected at a greater distance, or it was caught during an early-stage outburst, shedding material and temporarily boosting its visibility. Contemporary observations show gradual brightening rather than a precipitous flare, nudging the interpretation toward the larger-fragment scenario.

These sungrazers live dangerous lives. They plunge along extreme, highly elongated orbits that deliver them to the Sun's doorstep. For MAPS that doorstep is exceptionally close: predictions place its perihelion at roughly 120,000 kilometres above the solar surface in early April. That is tiny on solar scales, and the tidal and thermal stresses there are enormous. Many comets do not survive such passes; some disintegrate entirely, others fragment and briefly surge in brightness as fresh ice is exposed to sunlight.

Comet Ikeya-Seki and its kin teach a useful lesson: proximity to the Sun can create the greatest shows, but it is also a lethal environment. Survival is uncertain, spectacle provisional.

Comet Ikeya-Seki, captured on October 29 1965.

What to expect in April — and why we watch

So what might observers see? Short answer: it depends. If MAPS holds together as it grazes the Sun, it could become a striking evening object in early to mid-April, particularly visible from southern latitudes. If it endures a near-complete heating without full disintegration, observers on Earth may even glimpse it during daylight hours as a bright, condensed core with a sweeping tail. That is an exceptional circumstance; the better-known precedent is Ikeya-Seki, but even that comet's nucleus was likely much larger than MAPS is expected to be.

If MAPS breaks apart at or just after perihelion, astronomers might nonetheless be rewarded. Fragmentation often releases large quantities of dust and gas, which scatter sunlight efficiently and can produce sudden, unpredictable brightening. For live-monitoring, that is the kind of event both professional solar observatories and backyard enthusiasts crave: sudden, dramatic, and rich in physical information.

Space-based assets will be crucial. SOHO (the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory) has recorded thousands of tiny Kreutz fragments over the past three decades; most are meter-sized or smaller and only visible when they plunge toward perihelion. A larger fragment like MAPS gives SOHO and other solar imagers an opportunity to study how cometary material responds to extreme solar heating, how dust production evolves near perihelion, and how the solar wind and magnetic field interact with rapidly expanding cometary comae.

On Earth, the viewing geometry favors the southern hemisphere. After perihelion, the comet will drop into the evening sky where observers with clear horizons and minimal light pollution will have the best chance. Casual skywatchers should plan for twilight observations in early April, though the precise calendar depends on the comet's exact perihelion epoch and any changes to its brightness trend in the weeks beforehand.

The technical discovery image of comet MAPS.

Beyond spectacle, MAPS is scientifically valuable. Sungrazers are natural laboratories for studying volatile chemistry under intense solar heating; they reveal how ices sublimate, how refractory dust is liberated, and how short-lived radicals and ions form when molecules are ripped apart by ultraviolet radiation. For planetary scientists and heliophysicists alike, the composition and behavior of a relatively fresh fragment near the Sun can refine models of cometary structure and the processes that govern comet-solar interaction.

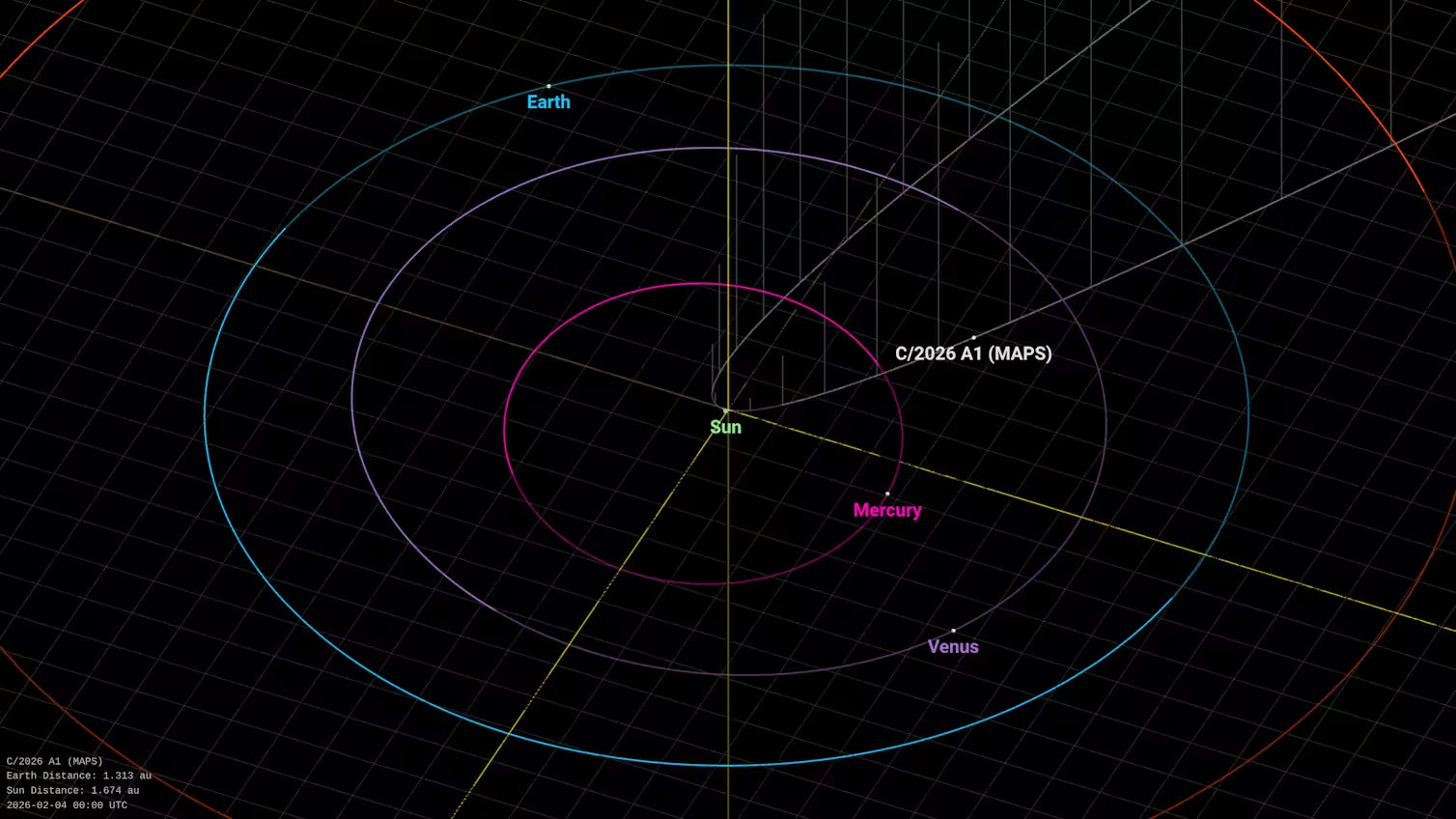

Technically minded observers will also follow the orbit. The JPL Small-Body database and orbit viewers will update as new astrometry refines predictions. Those orbital refinements improve when amateurs and professionals both contribute measurements — a reminder that comet science remains one of the most collaborative branches of observational astronomy.

Comet MAPS is en route to graze our Sun.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Rios, an observational comet specialist at a national university, puts the situation plainly: 'Sungrazers are a gamble. When one arrives this early in the year and is visible from a large aperture, we get a twofold benefit: immediate opportunities for solar imagers, and a months-long campaign for ground observers. Even a modest fragment teaches us about material strength and volatile layers — details that are hard to infer from distant comets.'

She adds, 'If MAPS survives perihelion, the post-perihelion tail and coma evolution will be particularly telling. If it fragments, the timing and speed of that break-up tell us about internal structure — whether the nucleus was a loosely bound rubble pile or held together by more cohesive forces.'

Beyond academic curiosity lies public engagement. Great comets have historically riveted the public imagination. A visible sungrazer sparks a unique blend of amateur joy and scientific urgency: thousands of observers capturing images, timing brightness changes, and feeding data into models in near real time. For solar physicists, that flood of observations is a rare chance to tie in-situ and remote-sensing data to a single, time-sensitive event.

What should skywatchers do now? Monitor updates. Professional surveys and the JPL orbit pages will refine predictions. If you plan to observe, prepare for twilight sessions in early April, bring binoculars or a small telescope, and follow safety guidance: never look directly at the Sun without proper solar filters. Many will follow the live SOHO feeds for perihelion coverage — the safest and most consistent way to watch the encounter.

Will MAPS become a headline-making comet? Maybe. The odds favor some level of drama: either the comet becomes a bright survivor or it disintegrates in a spectacular fashion. Either way, the Sun has called this fragment to a high-stakes rendezvous, and for a few evenings in April the sky may remind us how dynamic the solar system still is.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment