5 Minutes

A familiar respiratory microbe has been found hiding where you least expect it: at the back of the eye. Researchers report higher levels of Chlamydia pneumoniae in the retina of people with Alzheimer's disease, a finding that reframes the way scientists think about infection, inflammation and neurodegeneration.

From lungs to retina: what the study did and why it matters

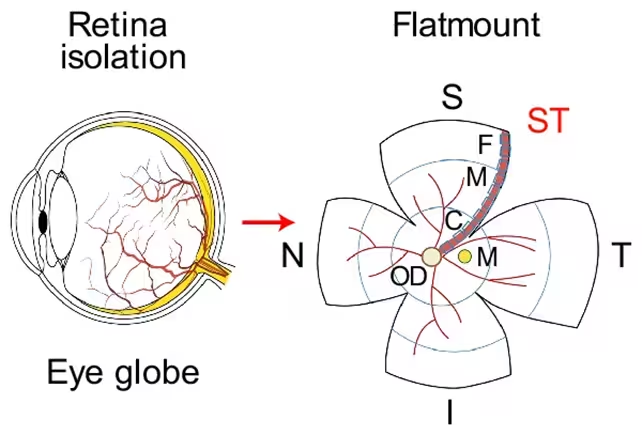

The work, led by a team at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, examined eye and brain tissue from 104 deceased individuals spanning normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's. The investigators focused on the retina — the thin, neural tissue that converts light into the electrical signals our brains use to build vision — and searched for signs of C. pneumoniae, a bacterium usually associated with bronchitis, pneumonia and sinus infections.

They saw a clear pattern: people with Alzheimer's had greater amounts of the bacterium in both retinal and brain tissue, and those higher loads correlated with more severe cognitive decline. Genetic risk also showed up. Tissue from donors carrying Alzheimer's-linked APOE variants contained more of the bacterium than tissue from people without those alleles. The distinction between healthy controls and those with MCI was less stark, suggesting the signal strengthens as pathology advances.

Laboratory tests, mechanisms and the limits of the evidence

Correlation alone cannot prove cause. The team knew that, so they moved into cell and animal models to test what the microbe might actually do. Infected neuronal cultures and infected animals developed more inflammation, greater neuronal loss and larger deposits of amyloid-beta — the sticky protein fragments that clump in Alzheimer's brains. In plain terms: introducing this bacterium amplified processes already tied to neurodegeneration.

What might that amplification look like at the molecular level? The researchers point to an inflammation pathway targeted by C. pneumoniae that appears to intensify the immune response in neural tissue, possibly tipping already vulnerable cells toward dysfunction and death. The authors describe the bacterium as an amplifier rather than the primary trigger — one contributing factor in a disease with many moving parts.

“The eye is a surrogate for the brain,” said neuroscientist Maya Koronyo-Hamaoui of Cedars-Sinai. “Retinal bacterial infection and chronic inflammation can reflect brain pathology and predict disease status, supporting retinal imaging as a noninvasive way to identify people at risk for Alzheimer's.”

Still, important questions remain. Could C. pneumoniae be an opportunist that colonizes tissue already damaged by Alzheimer's processes? Are certain people more susceptible to retinal colonization? Longitudinal and interventional human studies will be needed before clinicians can act on these findings.

Implications for detection and treatment

There is pragmatic appeal here. The retina is accessible: ophthalmic imaging technologies like optical coherence tomography (OCT) and advanced molecular retinal scans are far less invasive than brain biopsy or some forms of neuroimaging. If retinal infection reliably tracks with brain pathology, a noninvasive eye test might one day flag people at elevated risk and direct them toward earlier interventions.

Therapeutically, two avenues open. One is antimicrobial: could targeted antibiotics or microbe-directed immunotherapies reduce the bacterial load and blunt downstream inflammation? The other is anti-inflammatory: if infection drives an overactive immune response that accelerates neurodegeneration, tamping down that response might slow progression. Neither approach is proven; both will require careful trials because altering immune or microbial communities in older adults carries risks.

“This discovery raises the possibility of targeting the infection-inflammation axis to treat Alzheimer's,” noted biomedical scientist Timothy Crother, also at Cedars-Sinai.

Expert Insight

Dr. Serena Malik, a neuroimmunologist who was not involved in the study, says the results fit a growing picture in which peripheral infections and chronic inflammation influence brain health. “We've known that systemic inflammation can exacerbate cognitive decline,” she explains. “Finding C. pneumoniae in the retina gives us a concrete anatomical bridge to study how that peripheral signal reaches the brain. It doesn't mean every Alzheimer's case is infectious, but it does expand the list of modifiable factors to investigate.”

The study injects new urgency into work connecting eyes and brains. It also underscores complexity: Alzheimer's is unlikely to yield to a single cure. But by revealing a possible microbial amplifier in a tissue easy to examine, this research points toward testable strategies — new biomarker pathways, targeted therapies and, perhaps, a future in which a simple eye scan helps guide dementia care and prevention.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

labflux

Wow, bacteria in the back of the eye linked to Alzheimer's? If true this could change screening, but maybe it's just an opportunist colonizing sick tissue. Need long followup studies, pronto

Leave a Comment